Introduction

Metropolis is a silent film by German director Fritz Lang, belonging to the category of expressionist cinema. The film focuses on a dystopian world that reflects both the teleology of a utilitarian ideology of Western origin and contemporary issues of a transhumanist and technological nature in a visionary manner. Set against the turbulent backdrop of the Weimar Republic, Metropolis boldly reflects on humanity, technological progress, and the social challenges of a rapidly changing world. These elements form the main subject of the present reflections.

What characterizes Metropolis is its visual brilliance, which immerses the audience in a kaleidoscopic cityscape. The monumental skyscrapers, steaming factories, and labyrinthine underground canals create a surreal urban world whose realism draws the viewer into the intricacies of a ‘Dämonie der Großstadt’1 (cf. Sauermann 2004). The city itself, depicted as a leitmotif in the film, serves as a reflection of human ambitions and societal structures, notably showcasing elements of capitalist power dynamics. All the characters portrayed in the film, whether prominent or poor, function as archetypes representing deeper socio-critical issues. In this regard, the protagonist Freder, son of the powerful industrial magnate Joh Fredersen, stands in the middle of the social fabric, while the rebellious Maria serves as the voice of the oppressed. A story of love, power, and revolution unfolds between these two poles, delving into the deepest layers of the human psyche and revealing institutionally established patriarchal power dynamics and practices.

This article aims to reflect on Lang's technological imagination, which is expressed in the futuristic machines, robots, and other elements, in terms of cultural criticism. Metropolis not only casts a glance into the future but also deconstructs questions about the ethical and moral consequences of technological progress and the manipulation of nature, embodied through the figure of Maria, who transforms into a demonic cyborg named “HEL”2. Therefore, another aim of the article is to explore the symbolic depth of ‘Metropolis’ from a mythological perspective, examining its portrayal of a utilitarian social structure and highlighting the film’s political relevance within its historical context. Additionally, the narrative intricacies of Fritz Lang's cinematic storytelling, which have cemented his work as a timeless classic, should be emphasized.

1. The Vertical Dominance of the Machine

Metropolis begins by depicting the city's pyramidal structure and its deeply entrenched hierarchal social system. Both the script and the mechanical aspects of the machinery are limited to either horizontal-vertical or circular-closed movements. The opening sequence portrays the infernal mechanics of Metropolis, emphasized by a musical rhythm in crescendo and an unconventional ten-hour work shift endured by the laborers during their shift change.

Figure N° 1. Workers’ shift changing and ten-hour work rhythm

Source: Metropolis, seq.: 03:47-04:07

Fritz Lang employs visual editing effects to showcase the vertical machinery of an initially ‘invisible power’. The script moves backwards, guiding us to the underground Workers City (German: Stadt der Arbeiter), the deep-seated roots of industrial authority (seq. 05:21-06:04), while the elite at the bosses lead a supposedly normal and standardized utilitarian life, celebrating their achievements. The use of inverted film subtitles is particularly noteworthy. Subtitles for the working-class characters move strangely from top to bottom, while those for the privileged-class characters can be read from bottom to top. This contrast in subtitle movement reflects the dialectic of class struggle and the vertical structure of capitalist-liberalist power. Jacques Guigou and Jacques Wajnsztejn discuss this phenomenon as part of a ‘capitalized society’, highlighting the duality of the “verticality of power and the horizontality of exchange” (Guigou/ Wajnsztejn 2010), graphically portrayed in the film. In addition, the uniform workers at the beginning of the film symbolize the consequences of a uniform, enslaved, and alienated mass of people in which the individual as such seems to have lost his own subject identity. In this context and drawing parallels to the totalitarian power practices of National Socialism – which are also visionary deconstructed in Metropolis –, Adorno and Horkheimer emphasize in ‘Dialectic of Enlightenment’ the mechanisms of ideological conformity experienced by individuals. They argue that the same individuals are no longer able to exist as independent subjects but are rather subjected to the dictates and imperatives of uniformity. Interestingly, the film exhibits the potential for uniformity in a self-reflexive and self-referential manner, exposing castration discourses through the scene mentioned above. Adorno and Horkheimer notice in this regard:

In contrast to the liberal era, industrialized culture can allow itself to be as indignant about capitalism as the folk culture, but not to reject the threat of castration. This is its very essence. It outlasts the organized relaxation of morals towards uniform wearers in the cheerful films produced for them and ultimately in reality.3 (Adorno/Horkheimer 2016: 130)

2. Narratives of Vitalism

In the film, the miserable subterranean working-class world is juxtaposed with the world of a reckless elite, which Freder, among others, appears to enjoy without limits. The scene of the artificial paradise symbolizes decadent hedonism, depicting submissive women whose sole purpose is to satisfy male greed and lust. This allegory, along with the filmic commentary title “The Wonder of the Eternal Gardens” (Metropolis, 07:30), suggests that Freder’s world is more of an illusory paradise. Thus, the film employs a ‘deception effect’, presenting an ambivalent spatiality of Eden and decadent Babylon through its garden motif.

Figure N° 2. The wonder of the Eternal Garden

Source: Metropolis, seq. 07:58-9:33

Also noteworthy is the portrayal of fetishized female characters serving libidinous male desires, who are supposed to “have the honor of entertaining master Freder, Frederson’s son” (Metropolis, seq. 08:04), as highlighted by the house servant. This underscores a second manifestation of patriarchal discourse rooted in obsessive Epicureanism. Metropolis satirically parodies the biblical Genesis narrative while deconstructing its commandment: “[…] Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it.” (The Bible. Old Testament, 1996: Genesis. 1:28). In this context, vitalist discourses can be situated on two levels: firstly, the fascistoid ideologies of a vitalist way of thinking are anticipated. Secondly, Fritz Lang problematizes the monopolization or appropriation of vitality by a powerful elite through the topographical opposition of both worlds – namely the seemingly a-vitalist workers and the “vitalist-ecological” world of Freder’s privileged class. On the other hand, Lang – following Inga Pollmann – aims to employ vitalistic film motifs that appear to parody Uexküll's Umwelt4 concept intertextually. Pollmann again observes that the Manichean concept of the categorical division of the human (environmental) world into good and bad, or weak and strong, resonated strongly in film production of the interwar period.

The resurgence of vitalist motifs in post-war film theory should surprise us, for classical accounts of vitalism see this as a movement that achieved its apotheosis when it merged with Nazi ideology in the Third Reich, where holism and the idea of the state as an organism served to justify an aggressive foreign policy and racial ideologies; it is not difficult to detect, for example, the chilling resonance between this political interest in holism and Uexküll’s idea of the Umwelt of the state. In the interwar period and during WWII, in other words, a politicized notion of life encouraged value distinctions between good and bad forms of life, and fueled the idea of ‘cleansing’ the state organism, a goal that was then used to justify radical measures against ‘harmful elements’ […]. (Pollmann 2018: 207)

As Freder searches for Maria, he unwittingly descends into the harrowing underground realm of labor, where individual identity dissipates amid collective anonymity. In this oppressive environment, the infernal, steam-filled, temple-like ‘Heart Machine’ emerges as a powerful allegory, representing a relentless teleology of blind progress at the cost of human sacrifice.

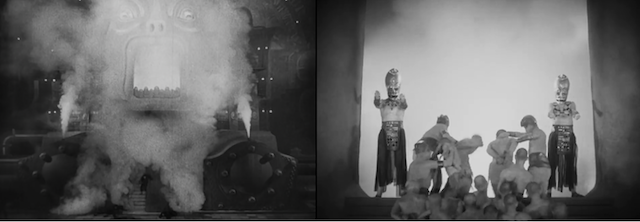

3. The Demonic Cult of Progress

The film’s narrative structure portrays the blind cult of progress and its demonic dimension. The Heart Machine, depicted as uncontrollable and perilous, serves as a central symbol. The character ‘Rotwang’ – a reclusive mad scientist – embodies a Faustian archetype of modernity. Metropolis illustrates the destructive effects of industrial civilization by depicting the surrealistic and demonic metamorphosis of the Heart Machine into a biblical Moloch (a deity associated with child sacrifice) following an explosion. Freder alone recognizes its concealed form. The sacrificial scene, occurring around the 15th minute, evokes strong parallels with the Holocaust, symbolized by entangled, shaven victims.

Figure N° 3. The Heart Machine turning to Moloch

Source: Metropolis, seq. 15:36-15:55

The transformation of the so-called ‘Heart Machine’ into the demonic Moloch figure, which embodies sacrificial rites from a cultural anthropological perspective, is ambiguous. On the one hand, it refers to a process of the return of the same, for the idea of human sacrifice is resumed for the benefit of superior destructive powers. On the other hand, the Moloch myth, stylized polysemically in the film, symbolizes abstract mechanisms of sacrifice that transcend their mythological origins and manifest as macro-structural systems of oppression in the post-industrial era. Freder emerges as the sole witness to the demonic transformation, recognizing and naming it during the surreal catacomb scene. It is as if he secretly knew that the anthropophagic Heart Machine, sustaining the entire technical balance of Metropolis, operates through permanent regulation involving human sacrifice. Consequently, it acquires the aura of a sacred divinity to which Metropolis’s inhabitants are blindly subdued in the name of a utilitarian ideology of technical progress. Anthropologist Walker Burkert similarly explores these themes in his ‘Anthropology of Ancient Sacrificial Myths’:

Sacrificial killing is the basic experience of the ‘sacred’. Homo religiosus acts and attains self-awareness as homo necans. Indeed, this is what it means “to act”, […], operari (whence ‘sacrifice’ is Opfer in German) – the same merely covers up the heart of the action with a euphemism. The bliss of encountering divinity finds expression in words, and yet the strange and extraordinary events that the participant in the sacrifice is forced to witness are all the more intense because they are left undiscussed. (Burkert, 1983: 3).

Freder also embodies the complexities within consumer society, portraying the dual challenges and utopian aspirations associated with controlling technological progress. His identification with the working class, reduced to being merely an identification number, serves as a poignant representation of these themes. Joh Fredersen seeks out Rotwang, epitomizing the archetype of the blindly ambitious and corrupting scientist, in an attempt to find a solution to the unstable Heart Machine and the growing unrest among his workers. This subplot unfolds within Rotwang’s forgotten home laboratory situated in the city’s center. Here, Fredersen aims to infuse the human soul of his deceased wife into a creation resembling an Eve of the future – a trans-humanoid species called HEL. Accordingly, and similar to Mary Shelley's mythological story of the monster created by Frankenstein, Metropolis depicts a paradigm shift that significantly influences the telos of the post-industrialized ideology of progress. Ulrich Beck's concept of the risk society can therefore be re-situated in this context:

This risk society results from the changing nature of science. Once upon a time, science was confined to the laboratory – a spatially and temporally confined site of science. Although there are examples of science escaping – most famously in Mary Shelley’s story of the monster created by Frankenstein – generally, this does not happen. (Beck, 2014: vii).

The pursuit (seq. 40:39-41:44) articulates a discourse of rationalization and sharpens the utopian vision of unrestricted and perfectible progress.

4. Transhumanism, Apocalypticism and the Principle of Hope

The futuristic and cybernetically portrayed animation of HEL might evoke a in-difference between man and machine. Simultaneously, a proletarian rebellion brews in the catacombs of the city. Here, Maria unexpectedly emerges as a self-assured ‘prophet of hope’ for the workers. Meanwhile, Joh Fredersen and Rotwang concoct a Machiavellian plan to counteract this uprising. Both characters appear to engage in a pact with the Devil; Rotwang intends to steal Maria's soul to assume her identity, thereby enabling the manipulation of the masses once more.

Accordingly, the transfiguration scene of HEL into the new Maria figure employing Rotwang's experiment evokes a possible intertextual reference to Goethe's Faustus myth: the eponymous protagonist famously sells his soul to the diabolical Mephistopheles. However, the devil's pact re-mythologized in the film is stylized differently. The myth of perfection no longer refers to the protagonist Faust – here incarnated by Fredersen – but suggests the hybrid materialization of the new Maria figure, which transcends the fatality of death. The latter, as a female counterpart, also embodies the myths of eternal youth and vitality, which are also thematized in Goethe's tragedy. The science fiction film thus depicts the dangerous and destructive consequences of an unrestricted “demonic” belief in progress. In his study of Faust, David Hawkes rightly situates Goethe's Faust myth with the problem of materialized entelechy, which gives rise to existential questions of physical transcendence. According to him, one danger lies in the tempting determination of this materiality as telos and essence, a theme also explored in the film. Hawkes, in connection with the Faust myth, states:

The entelechy is the principle of form immanent within matter, and also the goal, or telos, toward which life naturally progresses. Goethe uses the term as a syncretic approximation of the Christian ‘soul’; he originally wrote ‘entelechy’ where the final scene of Faust refers to the hero’s ‘immortal part’ […]. Although entelechy is immanent in the body, it is simultaneously transcendent of it: it is an immaterial, nonextended substance that, therefore, ‘cannot be represented.’ It is also that which raises humanity to a qualitatively ‘higher’ level of existence than the rest of sublunary creation. Paradoxically, however, being corporeal, humanity naturally communicates, expresses, or ‘represents,’ entelechy through the medium of matter. The prime epistemological and ethical danger to which humanity is exposed is the temptation to take this representation of the human essence for that essence itself. Goethe’s Faust undertakes to show what happens when we submit to this temptation, and to illustrate how any attempt to reduce entelechy to a material or quantitative level necessarily entails its destruction. When entelechy is reduced to numerical or figurative form it ceases to be what it is: it ceases to exist. (Hawkes, 2007: 152).

Towards the 01:40:00 sequence, the new “cybernetic” and no longer controllable “messianic” Maria assumes the role of a false prophetess, seemingly inciting the working masses to engage in a violent revolution. The spatiality of this scene, set in the underground world and resembling a temple-like cult, is remarkable. The conclusion of the interlude holds strong relevance to contemporary technological issues, vividly depicting the modern dilemma of transhumanism through the transfer of Maria’s soul into the metal HEL machine:

Figure N° 4. HEL’s Metamorphosis into Maria

Source: Metropolis, seq. 01:24:34-01:25:44

Fritz Lang's Metropolis thus serves as an eschatological premonition of the teleology of destructive progress, allegorically personified by the cyborg HEL. Similarly, the narrative of transcending death emphasized in this allegory underscores the holographic aspect of the HEL figure, projecting an immortality probably stemming from the utopian philosophy of traditional utilitarianism. According to Kurzweil's and Tirosh-Samuelson's conception of transcendence, a dialectic of the material and immaterial takes permanently place in the film, foregrounding the ambivalent dimension of this technological narrative:

For Kurzweil, this is a form of immortality, although he concedes that the data and information do not last forever; the longevity of information depends on its relevance, utility, and accessibility. According to Kurzweil, here lies the meaning of transcendence, which he takes literally to mean “to go beyond,” that is, “to go beyond the ordinary powers of the material world through the power of patterns.” Yes, the body, the hardware of the human computer, will die; but the software of our lives, our personal “mind file” will continue to live on the Web in the posthuman futures where holographic avatars will interact with others without bodies. (Kurzweil, in: Tirosh-Samuelson, 2011: 17-18).

This demonic portrayal of Maria ultimately allegorizes the deceptive “new” decadent Babylon that misleads the masses. From a film semiotic perspective, this effect is achieved through hypnotic and bewildering lighting techniques, recurring eye motifs, and props. The illusion of goodness and splendour suggested by the remythicization of the supposedly triumphant Babel Tower construction also proves to be a deception of the masses in Metropolis. In a surrealistic way, the false Maria takes the form of a Babylonian goddess in the film, who also misleads the overly ambitious class of the rich. This problematizes the idea of a principle of hope pursued since modernity, which the philosopher Ernst Bloch even associates with the capitalist discourse of the Hollywood film industry. This results in a kind of pantomimic “mirror effect” of a utopia of hope, ultimately articulated as a narrative in the film's conclusion. Bloch states the following:

In general therefore the film, in that it is capable through photography and microphone of incorporating the whole of real experience in a streamlike mime, belongs to the most powerful mirror- and distortion- but also concentration-images Which (sic) are displayed to the wish for the fullness of life, as substitute and glossy deception, but also as information rich in imagery. Hollywood has become an incomparable falsification, whereas the realistic film in its anti-capitalist, no longer capitalist peak performances can, as critical, as stylizing film and as mirror of hope, certainly portray the mime of the days which change the world. The pantomimic aspect of the film is ultimately that of society, both in the ways in which it expresses itself and above all in the deterring or inspiring, promising contents which are set out. (Bloch 1995/1959: 459-460)

So Metropolis concludes with the rescue of the city’s children (symbolizing the triumph of Good) from the flood generated by the uncontrollable Heart Machine, the exposure of Rotwang's deceitful schemes, and the symbolic burning of HEL, depicted as a witch-like figure.

Conclusion

Metropolis draws parallels to the science fiction genre, echoing Susan Sontag’s notion of “imagination of disaster” (Sontag 1965). Lang’s film intricately exposes and deconstructs the idealized concept of blinding progress, portraying its telos (purpose) as an apparatus of ideology and power. Indeed, the film reveals patriarchal-totalitarian mechanisms and systems of oppression characterized by hierarchical, vertical authority, controlled by other (invisible) entities. The narratives within the film depict a ‘Dialectic of Enlightenment’ (in the sense of Adorno and Horkheimer), shedding light on the taxonomies and paradigms of modernity through their ambivalence and indifference. Metropolis, in a visionary manner, prompts critical reflections on civilization and culture regarding the pursuit of perfectible progress. This unbridled pursuit often leads to catastrophic totalitarianism, akin to National Socialism. Following Hans Blumenberg’s concept of “work on myth” (Blumenberg 1988: 61), Metropolis illustrates a phenomenology that reveals the underlying myths within utilitarian and totalitarian discourses. Beyond and despite its critiques of civilization and culture, Metropolis reimagines the utopian ideals of modernity. Through its conclusion, the film suggests that the longed-for harmony between nature and culture is achieved through a relativization of reason as the absolute standard that has dominated the discourse of progress since the Enlightenment. In this way, Fritz Lang's film deconstructs, in a postmodern fashion, the entelechy of blind progress, which is depicted as a totalitarian cult in the film. It exposes a machinery of coercion and control imposed on the masses. Furthermore, the narrative structure of the film relies on dialectical elements that are in paradigmatic opposition to each other, articulating vitalist and a-vitalist discourses through the narrative, and thus shaping the plot structure significantly. In addition, the futuristic nature of Metropolis as a science fiction film – more precisely through the figure of the HEL cyborg – projects the eschatological and apocalyptic vision of a current paradigm shift, namely that of a homo digitalis. The topical character of the film lies in its questioning of transhumanism, a concept still controversial today, and its potential to draw attention to the current dilemma of artificial intelligence. Metropolis warns, in an allegorical and metaphorical way, against any blind progress that may spiral out of control. The film possibly envisions a utopian scenario encapsulated by the motto: “The mediator between the brain and the hands must be the heart”, suggesting a harmonious balance between intellect and affect.