Introduction

The study of the critical term in Arab modern and contemporary thought constitutes a crucial entry point into understanding the epistemological foundations of Arab literary criticism. While the Arabic intellectual tradition is marked by a rich terminological heritage rooted in rhetoric, grammar, theology, and philosophy, the encounter with modernity—driven by translation, Arabization, and the proliferation of Western critical theories—has introduced new challenges and disrupted the coherence of critical discourse.

This disruption is not merely terminological in nature; it is epistemic. The lack of consistency in the use and conceptualization of critical terms across the Arab intellectual landscape has generated semantic ambiguity, interpretative confusion, and methodological fragmentation. In this context, the critical term becomes more than a lexical item—it becomes a carrier of theoretical assumptions, historical tensions, and disciplinary alignments.

This study aims to investigate the origins, mechanisms, and epistemological relationships that shape the Arab critical term. It draws on both classical Arab sources (such as Al-Jahiz and Ibn Hazm) and modern thinkers (including Abd Essalam El-Masadi and Youcef Waglisi), to trace the intellectual genealogy and linguistic dynamics of term formation. Particular attention is given to the processes of derivation, metaphor, Arabization, translation, and linguistic carving. Through a critical and interdisciplinary lens, the article calls for the construction of a unified Arab critical lexicon that responds to contemporary scientific needs while remaining grounded in cultural specificity.

1. Theoretical and Historical Foundations of the Critical Term

The emergence of the critical term in Arab intellectual history is not a recent phenomenon nor a simple borrowing from Western literary traditions. Rather, it is deeply rooted in a classical legacy where language, thought, and critique were tightly interwoven. The early Arab rhetoricians, grammarians, and theologians understood that the precision of expression was fundamental to the articulation of knowledge. Thus, the critical term—understood as a specialized lexical unit that conveys a precise theoretical concept—has long existed within the structure of Arabic scholarly discourse.

Notably, Al-Jahiz (9th century), in his Al-Bayan wa al-Tabyin, articulates the distinction between the name and the meaning, emphasizing that names carry no inherent virtue or deficiency apart from their assigned function. This early linguistic awareness reflects a foundational concern with semantic clarity and contextual accuracy, principles that underpin all terminological discourse. Similarly, Ibn Hazm (11th century) stresses the need for each science to develop its own vocabulary, with specialized terms that condense and transmit complex meanings efficiently—a view remarkably close to modern understandings of terminology.

These classical reflections reveal that terminological consciousness existed well before the advent of modern literary theory. However, it is during the post-colonial Arab intellectual renaissance, especially in the second half of the 20th century, that the issue of critical terminology gains prominence. The influx of translated critical theories—from structuralism to postmodernism—created a terminological explosion in Arabic discourse. Many concepts were imported through translation, often without rigorous adaptation, resulting in conceptual overlaps, ambiguous meanings, and contradictory usages. The rapid adoption of foreign terms—sometimes via literal translation and sometimes via Arabization—fueled a growing sense of semantic instability in Arab literary criticism.

At the heart of this instability lies a complex relationship between heritage and modernity. Arab scholars found themselves negotiating between a rich, linguistically fertile classical tradition and the demands of modern theoretical rigor. In many cases, this negotiation led to the reactivation of classical terms with new meanings—an act of semantic reconfiguration that both enriched and problematized the terminological landscape.

Contemporary scholars have attempted to address this challenge. Abd Essalam El-Masadi, for example, argues that any valid critical term must satisfy three core criteria: cognitive precision, linguistic anchoring, and methodological functionality. Without these, a term risks becoming obscure, ideologically unstable, or methodologically irrelevant. Similarly, Youcef Waglisi adopts a semiotic and grammatical perspective, suggesting that the critical term must exhibit morphological coherence, semantic unicity, and conceptual operability within a defined discursive system.

From this theoretical lens, the Arab critical term is not merely a linguistic sign; it is a semiotic construct embedded within larger structures of knowledge and power. It functions as both a cognitive tool and a marker of disciplinary identity, reflecting the intellectual tensions that shape Arab literary studies today.

In sum, the historical and theoretical foundations of the Arab critical term reveal a tension between inheritance and innovation, between linguistic rootedness and epistemological expansion. Understanding this genealogy is essential for any attempt to unify or standardize critical terminology in the contemporary Arab scholarly context.

2. Mechanisms and Dynamics of Term Formation

The development of critical terminology in the Arab intellectual landscape has been shaped by a multiplicity of mechanisms. These mechanisms are not merely linguistic tools; they are epistemological strategies that reflect the Arab scholar’s attempt to reconcile heritage with modernity, and local specificity with global discourse. Six major mechanisms dominate this landscape: derivation, metaphor, revival, Arabization, translation, and lexical carving. Each of these practices carries its own theoretical implications, operational challenges, and cultural weight.

2.1. Derivation (Al-Ishtiqāq)

Derivation is among the most authentic and productive methods of term creation in the Arabic language. It refers to the formation of new lexical items from a root through morphological processes that preserve semantic continuity. Root-based derivation is deeply embedded in the internal logic of Arabic, where triliteral and quadriliteral roots serve as semantic nuclei from which dozens of related terms may be generated.

In critical terminology, derivation provides a way to construct terms organically, drawing on native linguistic resources without relying on foreign elements. For instance, the term taḥlīl (analysis) is derived from the root ḥ-l-l, which connotes dissolution or unpacking—conceptually consistent with the analytical process in literary critique.

Moreover, derivation preserves etymological transparency, allowing scholars and readers to intuitively grasp the semantic field of a term. It also enables conceptual expansion, as new forms can be generated for related ideas (e.g., naqd, nāqid, mantaq, mantiqī).

However, the limitations of derivation become evident when dealing with imported theoretical frameworks that lack semantic equivalents in Arabic. In such cases, derivation risks semantic stretching or misalignment if the morphological form does not correspond to the conceptual structure of the original term.

2.2. Metaphor (Al-Isti‘āra)

Metaphor, in the Arabic rhetorical tradition, is not merely a literary device but also a mechanism of conceptual abstraction. Many foundational critical terms in Arabic—such as mījās (analogy), isti‘āra (metaphor), and tashbīh(simile)—are themselves products of figurative transfer, wherein a familiar sensory domain is mapped onto an abstract conceptual domain.

In the modern period, metaphor continues to play a significant role in the formulation of critical vocabulary. Terms like al-marāyā al-naqdiyya ("critical mirrors") or al-khiṭāb al-muʿāriḍ ("oppositional discourse") are metaphorical expressions that condense complex theoretical frameworks into evocative, culturally resonant phrases.

While metaphor enriches language through imaginative resonance, it can also compromise semantic precision, especially in scientific or philosophical contexts. If left unstandardized, metaphorical terms may generate multiple interpretations, undermining the clarity and objectivity that critical discourse demands.

Furthermore, frequent metaphorization of terms may result in semantic fossilization, whereby the original metaphor becomes opaque and loses its explanatory power. This underscores the need for terminological regulation, especially in academic and interdisciplinary contexts.

2.3. Revival of Classical Vocabulary

Another common strategy is the reactivation of dormant or underused classical Arabic terms, a process referred to as iḥyāʾ al-mustalaḥāt al-qadīma. This mechanism draws on the symbolic capital of classical Arabic, using established but semantically flexible words to express contemporary theoretical constructs.

For example, the word ḥadath (event), which in classical Arabic signified a temporal occurrence, has been adapted to translate the French événement in poststructuralist theory, especially in Derridean and Badiouan contexts. Similarly, the term isti‘āra, historically a rhetorical figure, has been elevated to denote an analytical tool in semiotic and cultural studies.

This practice offers two main advantages: (1) it reinforces cultural legitimacy by grounding modern discourse in linguistic heritage, and (2) it minimizes the risk of alienation caused by excessive foreign borrowing. However, revival carries the danger of semantic distortion. Reassigned meanings may conflict with classical usages, generating confusion among readers trained in traditional disciplines.

Furthermore, the absence of a unified institutional framework to regulate semantic shifts results in multiple, sometimes contradictory, interpretations of the same term across disciplines and regions.

2.4. Arabization (Ta‘rīb)

Arabization, or the adaptation of foreign terms to Arabic phonological and morphological norms, became a dominant strategy in the 20th century, especially during the postcolonial period. As Arab intellectuals sought to absorb European literary and critical theories, they were faced with the challenge of translating an immense conceptual apparatus into Arabic.

Arabization operates in various forms:

-

Phonetic transcription (demokrātiyya, from démocratie);

-

Semantic approximation, where an Arabic term is chosen to match a foreign concept (al-ḥiṣāra al-thaqāfiyya for cultural hegemony);

-

Morphemic integration, which modifies the foreign term to fit Arabic morphology (istīrātījiyya for strategy).

Arabization has the advantage of semantic efficiency, enabling rapid conceptual transfer across linguistic boundaries. It also facilitates terminological convergence among Arab scholars, who can use standardized forms rather than ad hoc translations.

However, its disadvantages are non-negligible. Arabization may result in semantic opacity, particularly when the borrowed term is alien to Arabic linguistic logic or cultural referents. Additionally, inconsistencies between different Arabization efforts—across countries or institutions—have created a fragmented terminological landscape, undermining the goal of standardization.

2.5. Translation

Translation is perhaps the most powerful but also the most problematic mechanism in the Arab terminological system. As the primary channel for the reception of Western theories, translation has imported vast numbers of concepts into Arabic critical discourse. Yet this process has rarely been accompanied by rigorous conceptual calibration.

In many cases, literal translations fail to capture the nuanced connotations of the source term. For example, translating deconstruction as tafkīk or taḥlīl tafkīkī may strip the term of its philosophical and methodological complexity in Derrida's usage. Similarly, translating subjectivity as al-dhātiyya risks collapsing rich psychoanalytic, phenomenological, and postmodern layers into a flat, vague notion of selfhood.

Moreover, translation often leads to the proliferation of synonyms, with multiple translations for the same term coexisting without regulation (e.g., intertextuality appears as ta-nāṣ, tadākhul al-nuṣūṣ, or al-iḥāla al-naṣṣiyya). This polysemy undermines theoretical clarity and makes comparative research difficult.

Despite these challenges, translation remains indispensable. It is not only a linguistic act but also a cultural negotiation, shaping the very epistemic space in which Arab criticism operates.

2.6. Lexical Carving (Naḥt)

Lexical carving, or naḥt, refers to the creation of new words by fusing segments of existing words into a single composite unit. Though rarely used in classical Arabic, this method has gained traction in scientific and technical fields seeking concise and original expressions.

For example, the word ri’ālama has been proposed as a carved term for globalization (from riyāsa and ‘awlama). Similarly, naf‘ala could serve as a fusion of naqd (critique) and fi‘l (action), denoting praxis-oriented criticism.

Carving is innovative and can be productive when phonologically harmonious and semantically transparent. Yet it often risks sounding artificial or forced if the resulting term does not conform to Arabic morphological conventions. Moreover, such terms may remain unintelligible without explanatory context, reducing their communicative effectiveness.

Due to its experimental nature, carving requires institutional backing and scholarly consensus to gain legitimacy. Without these, it may remain marginal or symbolic rather than functional.

Each of these mechanisms reflects a different strategy of negotiation between language, thought, and identity. The coexistence of these processes explains the richness and instability of Arab critical terminology, and highlights the need for systematic reflection and coordinated regulation in the construction of a cohesive, functional critical lexicon.

3. Interdisciplinary and Epistemological Relationships

The critical term, by its very nature, cannot be confined within the boundaries of literary studies alone. Its formulation, evolution, and application depend on a dense network of interdisciplinary relationships, which reflect the epistemological hybridity of modern Arab criticism. These relationships span linguistics, semiotics, logic, philosophy, translation studies, and even the sociology of knowledge. The Arab critical term is, therefore, not simply a product of literary analysis but the intersection of multiple intellectual traditions, each contributing to its structure, function, and conceptual resonance.

3.1. Relationship with Linguistics and Semiotics

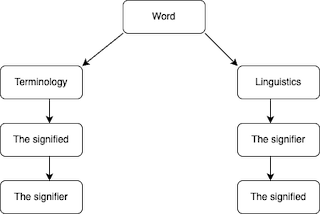

The most immediate and fundamental relationship is that between the critical term and linguistic theory. Since language is the medium through which critical thought is articulated, the term must align with linguistic principles of signification, structure, and usage. The influence of Ferdinand de Saussure's semiotic model—distinguishing between the signifierand the signified—has been particularly crucial for modern Arab critics such as Youcef Waglisi, who adopt this framework to analyze the internal mechanics of the term. In this model, a term must exhibit semiotic stability, meaning that its form (the signifier) and concept (the signified) must maintain a consistent and non-arbitrary relationship.

This alignment becomes even more vital in a multilingual context, where the signifier may shift dramatically across translations. In Arab critical discourse, many terms—e.g., discourse, structure, identity—carry polysemous traces, inherited from their Western origins and adapted through linguistic filters. Therefore, a failure to reconcile linguistic form with conceptual precision often results in terminological ambiguity and theoretical fragmentation.

Moreover, semiotic approaches encourage critics to view terms not as isolated entities but as nodes within larger systems of meaning. This perspective opens up pathways for analyzing terminological families, where clusters of related terms (e.g., subjectivity, agency, power) function together within ideological or theoretical paradigms. Consequently, the critical term becomes an analytical tool with system-wide implications.

It is important to distinguish here between the methodological orientation of linguistics and that of terminology. Whereas modern linguistics, especially in the Saussurean tradition, tends to begin with the signifier—the word as it appears in natural language—and then analyze or infer its signified, terminology follows an inverse path. It begins with a precise concept (the signified), often derived from a specific scientific or theoretical framework, and seeks to assign it an appropriate linguistic form (the signifier). In other words, linguistics is primarily descriptive, explaining how language functions organically, while terminology is constructive and normative, prescribing how concepts should be named to ensure clarity and communicative efficiency. This reversal of direction in semiotic logic can be schematically represented as follows:

Approches du mot : terminologie vs linguistique

3.2. Relationship with Logic and Epistemology

Beyond language, critical terminology is anchored in epistemological structures—that is, the ways knowledge is produced, validated, and communicated. Drawing from Aristotelian logic, many Arab theorists stress the necessity of definitional clarity, non-contradiction, and conceptual hierarchy in term construction. For example, terms must not overlap excessively in meaning, must adhere to their conceptual scope, and must correspond to their epistemic function within a discourse.

Critics such as El-Masadi argue that the monosemic function of the term is what grants it scientific legitimacy. A term should refer to one concept only in its specialized context, avoiding the semantic drift that characterizes ordinary language. This principle aligns with the rationalist tradition in Arabic scholarship, where terms serve as instruments for logical deduction and structured inquiry.

From an epistemological perspective, the critical term is thus more than a linguistic artifact—it is a cognitive mechanism. It enables the organization of knowledge into systematic conceptual frameworks, where each term participates in a network of relations: generic/specific, whole/part, cause/effect, etc. In this sense, critical terminology is deeply involved in ontological modeling, helping define the very structure of literary reality as conceived by criticism.

3.3. Relationship with Translation and Cross-Cultural Exchange

Translation plays a double role in the epistemology of the critical term. On the one hand, it is a vector of transmission, allowing Arab scholars to access and engage with global theories. On the other, it is a site of epistemic transformation, where concepts are reshaped, reformulated, or even distorted in their passage between languages.

The act of translation introduces a host of epistemological challenges. Terms born in one cultural and linguistic context may not have exact equivalents in Arabic, necessitating either semantic approximation or the creation of neologisms. This problem is especially acute for culturally loaded terms—such as hegemony, postmodernism, or deconstruction—which carry with them an entire historical and philosophical baggage.

Moreover, the translation process often reflects asymmetries of power. The Arab critical field has historically been in a position of reception, importing terms without always having the means to theorize them autonomously. This dynamic raises questions about the epistemic sovereignty of Arab criticism: Is it reproducing Western categories, or generating indigenous theoretical alternatives?

Scholars such as Mohammed Amhaouche and Ali Al-Qacimi have highlighted the importance of developing a context-sensitive translation strategy, one that respects the semiotic ecology of Arabic while also remaining faithful to the conceptual integrity of the source. This strategy entails a move from literal equivalence to functional and epistemological adequacy.

3.4. Relationship with Cultural and Social Realities

Finally, critical terminology is inextricably linked to the sociocultural matrix in which it operates. Terms do not float in an abstract conceptual space; they are embedded in discourses of power, identity, and resistance. In postcolonial Arab contexts, the adoption or rejection of specific terms can be an ideological act, signaling alignment with or opposition to certain worldviews.

For example, the acceptance of terms like hybridity, subaltern, or intersectionality within Arab literary criticism reflects a broader engagement with postcolonial theory, gender studies, and global cultural studies. Yet these terms often undergo semantic negotiation, as they are reinterpreted through the lenses of Arab-Islamic heritage, national identity, or sociopolitical urgency.

In this sense, the critical term is not merely a linguistic unit but a symbolic act, situated within historical struggles over meaning, legitimacy, and authority. It reflects the evolving tensions between tradition and modernity, locality and universality, and cultural authenticity and global intelligibility.

In sum, the Arab critical term functions at the intersection of multiple disciplinary domains. Its meaning, form, and function are shaped by linguistic, logical, epistemological, translational, and cultural factors. Any effort to stabilize or standardize this terminology must therefore account for its multidimensional nature, recognizing that its epistemological foundations cannot be separated from its interdisciplinary entanglements.

4. Towards a Unified Arab Critical Lexicon

The plurality of mechanisms, influences, and epistemological entanglements that have shaped Arab critical terminology has undoubtedly enriched the field. However, this richness has come at a cost: conceptual fragmentation, semantic instability, and a lack of institutional coordination have hindered the consolidation of a coherent and operational lexicon. The need for a unified Arab critical lexicon is thus not merely a linguistic aspiration but an epistemological and pedagogical necessity.

The current situation is marked by:

-

the proliferation of synonyms for a single concept, depending on the translator, region, or school of thought;

-

the confusion between classical and modern usages of terms, particularly when ancient vocabulary is reloaded with contemporary meanings;

-

and the discrepancy between specialized critical discourse and the broader academic or public reception of those terms.

Such inconsistencies weaken the ability of Arab criticism to function as a systematic field of inquiry, comparable to other international traditions in literary theory and cultural studies.

4.1. The Case for Standardization

A key priority in addressing this fragmentation is the standardization of critical terminology. Standardization does not imply uniformity or conceptual rigidity but aims to:

-

ensure semantic transparency;

-

promote intertextual coherence across academic publications;

-

and facilitate pedagogical transmission in teaching environments.

This process requires a collective effort involving linguists, literary theorists, translators, and terminologists. It also necessitates a trans-regional approach, where terminological debates are not confined to national academic silos but engage scholars across the Arab world in dialogue and consensus-building.

In short, standardization is not a technocratic imposition but a foundational step toward the consolidation of a robust critical infrastructure. By promoting terminological consistency without sacrificing conceptual flexibility, standardization enables Arab criticism to articulate its discourse with greater precision, coherence, and pedagogical effectiveness. It also opens the door to meaningful regional and international collaborations by establishing a shared referential framework. In this way, standardization becomes an act of intellectual empowerment rather than constraint.

4.2. Institutional Initiatives and Recommendations

A few initiatives have attempted to tackle the terminological issue at the institutional level. Bodies such as the Academies of Arabic Language in Damascus, Cairo, and Baghdad, and the Arabization Coordination Bureau in Rabat have contributed significantly to the development and codification of terminology. Similarly, academic journals like Al-Lisān al-ʿArabī and Al-Muʿjamiyya have opened important discursive spaces for terminological reflection.

Nonetheless, these efforts remain fragmented, unevenly implemented, and often disconnected from the evolving needs of literary criticism. To move toward a more effective framework, several recommendations can be proposed:

-

Creation of a pan-Arab critical terminological commission, involving representatives from major universities, language academies, and research centers.

-

Comprehensive inventory of existing terms, including translated, Arabized, and indigenous terms, with contextual definitions and usage examples.

-

Development of a multilingual, open-access digital lexicon, with cross-references to equivalent terms in English, French, and other major languages of criticism.

-

Integration of terminological training into graduate curricula for literature, linguistics, and translation studies.

-

Periodic revision and contextual updating of terms, based on academic consensus and field developments.

These initiatives must be guided by principles of conceptual clarity, contextual sensitivity, and functional applicability. The goal is not to freeze terminology into rigid molds but to provide a flexible yet stable epistemological infrastructure.

4.3. Lexicon as Epistemological Foundation

At its core, a lexicon is not merely a dictionary; it is an epistemological map. It defines what can be said, how it can be said, and what is intelligible within a given disciplinary frame. Without a stable yet adaptable terminological foundation, Arab literary criticism risks remaining in a state of conceptual improvisation, perpetually reactive rather than proactively generative.

A unified Arab critical lexicon would empower scholars to:

-

articulate original theoretical contributions;

-

engage more robustly with global intellectual currents;

-

and consolidate a shared discursive tradition, rooted in Arab cultural and linguistic heritage while open to universal critical inquiry.

Thus, a unified lexicon should be understood not merely as a linguistic tool but as a conceptual architecture that shapes the very possibilities of thought and interpretation. The power of criticism lies in its ability to frame problems, construct meanings, and mobilize categories—and this power depends heavily on the terminological instruments it deploys. Building a coherent, contextually grounded, and critically informed lexicon is, therefore, not optional; it is a prerequisite for the epistemological maturity and autonomy of Arab critical theory.

Conclusion

The development of critical terminology in the Arab intellectual context is neither accidental nor secondary. It reflects the broader trajectory of Arab critical thought as it moves between the gravitational pull of its classical heritage and the epistemological demands of the modern world. Through this study, we have demonstrated that the critical term in Arab literary discourse is not merely a linguistic tool but an epistemic construct that shapes—and is shaped by—the theoretical, historical, and institutional contexts in which it operates.

The multiplicity of mechanisms employed in term formation—derivation, metaphor, revival, Arabization, translation, and carving—testifies to the richness of Arabic as a language of knowledge. Yet this same multiplicity has also produced fragmentation, conceptual overlaps, and terminological inconsistency. These challenges are not simply linguistic but touch upon the very cognitive architecture of Arab literary studies. The absence of clear boundaries between disciplines, the lack of consensus over terminology, and the ad hoc nature of translation have contributed to a situation where terms often circulate without epistemological anchorage or shared understanding.

We have also seen that the critical term exists at the intersection of multiple disciplines: linguistics, semiotics, philosophy, logic, translation studies, and cultural studies. This interdisciplinarity is a source of vitality but also of instability. It places upon the term the burden of maintaining semantic integrity while traversing various conceptual landscapes. Furthermore, in the age of globalization and digital communication, Arab criticism cannot afford to remain epistemologically insular. Its terminological tools must be capable of dialoguing with international discourses without sacrificing local specificity or intellectual sovereignty.

What is required, then, is not a rigid unification of terms, but a strategically coordinated and reflexively guided lexicon—one that is both responsive to theoretical innovation and respectful of linguistic authenticity. This involves institutional collaboration, terminological training, and the systematic development of critical metalanguage. It also entails a shift in perspective: from seeing terminology as a static repository of meanings to viewing it as a dynamic epistemological system capable of adaptation, critique, and regeneration.

Ultimately, the fate of Arab critical terminology will reflect the fate of Arab criticism itself. If the latter is to claim its place as a mature and influential player in global intellectual debates, it must invest in the tools that make knowledge possible—foremost among them, a coherent, functional, and critically grounded lexicon.