Introduction

Semitic genitives are much investigated in generative grammar. However, Free Genitives (FGs) like (1&2) below are very less researched compared to Synthetic Genitives (SGs). The former are also known as Free States, and the latter Construct States (CSs). Different approaches like head movement, remnant movement, reprojection and recursive PF linearization have been employed in analyzing SGs, though only the former two approaches have been made use of in analyzing FGs, and will be referred to in this article.1 A FG like (1a), an analytic possessive construction, common almost cross-linguistically, consists minimally of a head N (possessum), GDC and genitive particle (Poss). The GDC and Poss constitute the Poss-phrase.2

-

a. al-bayt ħaqq ʕali

the-house.M.SG of Ali.3

‘Ali’s house’

b. ha-beyt h’adash šel ali

the-house. M.SG the-big.M.SG of Ali.

‘Ali’s big house’ -

a. al-bayt l-kabiir ħaqq l-midiir l-jadiid

he-house.M.SG the-big.M.SG of the-manager the-new

‘The new manager’s big house’

b. s-sayaara ħaqq ʕali ʔalli ʔištra-ha min ş-şiin

the-car of Al that (he).bought-it from the-China

‘Ali’s car that he bought from China’ -

a. ha-tmuna šel ha-xamaniot šel van gox

the-picture of the-sunflowers of Van Gogh

‘Van Gogh’s picture of the sunflowers’

b. al-muftaaħ ħaqq l-baab ħaqq s-sayyaara ħaqq ʕali

the-key of the-door of the-car of Ali

‘Ali’s car’s door’s key

c. al-sayyaara wa l-baas ћaqq l-mudarris wa l-midiir

the-car and the-bus of the-teachers and the-manager

‘The teacher’s and the manager’s car and bus’

Although head movement (or N0-to-D0 in the nominal domain) has accounted for FG properties like (1) and probably (2), FGs like (3), have been left open. In addition, from a minimalist perspective, head movement has been challenged. Remnant movement (RM) somehow accounts for some properties of FGs in (1-3), but fail provide a principled account for several properties as we will see in section (5). In this article, I develop an N-to-Spec approach to analyzing Semitic FGs, building on work of Matushansky (2006), Vicente (2007) and Shormani (2014), arguing that it is more adequate than those in the field in providing straightforward and principled accounts for the syntactic and semantic properties of FGs.4 The Poss involved in such a construction varies from language to another and in Arabic even from dialect to another, including ħaqq, bitaaʕ, tabaʕ, dyal and šel in YA, Egyptian Arabic (EA), Palestinian Arabic (PA), Moroccan Arabic (MA) and MH, respectively.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. In section 2, I outline the fundamental properties of Semitic FGs, pointing out how FGs differ from SGs. In section 3, I outline head movement and RM in the nominal domain. In section 4, I present my proposal. In this section, I apply the proposed analysis to simple FGs. In section 5, I tackle DP-internal structure of FGs, applying the proposed analysis to modified FGs, focusing on Mirror Image Ordering (MIO).5 In section 6, I tackle multiple FGs and apply the proposed analysis to account for such structures.6 Section 7 concludes the paper.

1. FG Properties

In this section, I outline the properties of Semitic FGs, contrasting them with those of SGs. Based on FGs in (1-3) above, the syntactic and semantic properties of Semitic FGs are outlined in (4i-viii):

(4)

The head N is FG-initial.

(ii) D in FGs is not phonetically null, rather it is al-/ha-//Poss(ħaqq/šel), hence, no definiteness spread.

(iii) No adjacency constraint is imposed on the head N and the Poss-phrase (see independent modifiers).

(iv) The genitive Case of the genitive complement is assigned/checked by Poss.

(v) The feminine marker –t does not surface on a feminine head N.

(vi) The head N is assigned a θ-role of a Possessee, Theme, etc. and the genitive complement a Possessor, Agent, etc.

(vii) The head N can be N1, N2 ...Nn, the GDC can be GDC1, GDC2… GDCn (3b).

(viii) The head N can coordinate with N1, N2 ... Nn, and GDC with GDC1, GDC2…GDCn (3c).

Thus, comparing (4i-viii) to those of CSs outlined in (Fassi Fehri 1999: 125f., Siloni 1997: 33ff), it is clear that FGs considerably differ from SGs. However, the most salient differences are those that concern the nature of D, modification, multiplicity and coordination. As for D, it is phonetically null in SGs,7 but in FGs it is realized as al-/ha-, which bans definiteness spread. In SGs, Gen Case is checked by D. In FGs, however, it is checked by the DPoss. Unlike SGs, i.e. there is no adjacency stipulation between the head N and its Poss-phrase, the head N’s modifiers (specifically APs) can be positioned between the head N and its Poss-phrase, which is impossible in SGs.

2. Previous Accounts of FGs: A critique

In this section, I focus on two approaches that have been adopted in the study of Semitic FGs, namely head movement and remnant movement. The former is best found in (Ritter 1987, 1988, 1991, Mohammad 1988, 1999, Fassi Fehri 1993, Ouhalla 1991, Danon 2001, 2002, Travis 1984, Borer 1988, 1996, 1999, Pereltsvaig 2006, Siloni 1991, 1997, Vardeas 2009), and the latter in (Shlonsky 2004, Sichel 2002, 2003, Cinque 2003, 2005). In N0-to-D0 approach, it is claimed that the head N raises and targets a functional head higher in the derivation (Sichel 2003: 448) in both SGs and FGs (albeit not identical). In RM, it is claimed that the head N moves as part of an XP (i.e. NP) in a “roll-up” or “snowballing” fashion (Pereltsvaig 2006). These approaches are investigated in detail in the sections 3.1 and 3.2, respectively.

2.1. Head Movement

Head movement is an approach not only to nominal domain phenomena, but it has also been employed in the clausal domain. It can be formulized as in (5) below.

(5)

Head movement = move α to β where both α and β are X0 and Y0, respectively.

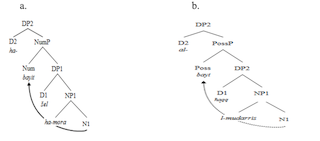

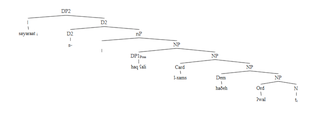

(5) states that α is X0 and β is Y0 and both of them are heads and no category which is not a head can move to a head and vice versa, thus satisfying Structure Preservation Condition (see Emonds 1970: 38). Thus, a head X is actually “a syntactically indivisible bundle of formal features” (Matushansky 2006: 69). Thus, in the pre-minimalist generative tradition, the head N of GS/CS, raises to D. However, regarding FGs, the matter significantly differs. Many linguists (e.g. Ritter 1988, 1991, Siloni 1991, Longobardi 1994, Fassi Fehri 1993) argue that because of the blocking effect caused by the Def al-/ha- (the) in FGs, there is very competing evidence for there being a maximal projection above N0 but lower than D0 to host the moved head. For instance, Ritter (1991) assumes that in Hebrew, the head N raises to a position lower than D0 and higher than N0.8 Thus, she proposes a functional phrase and calls it NumP where the head N moves to Num, but again employing N0-to-D0 movement. For Arabic FGs, Fassi Fehri (1993, 1999) proposes a functional phrase headed by Poss and claims that the head N of a FG raises and occupies it. His proposal is similar to Ritter’s (albeit not identical). (6a & b), derived in (7a & b), illustrate how FGs are derived by N0-to-D0 in MH and YA, respectively .

(6)

a. ha-bayit šel ha-mora (MH)

the-house of the-teacher

‘The teacher’s house’

b. al-bayt ћaqq l-mudarris (MA)

The-room of the teacher

‘The teacher’s room’

In (7a), for instance, Ritter argues that NumP is a functional phrase whose head hosts the moved head N as a solution to the problem of the head D being occupied by the Def article ha-. The Poss šel, according to Ritter, is positioned in D1 where it assigns Gen Case to the possessor ha-mora in Head-Spec configuration.9 In N0-to-D0, the head N raises past the šel-phrase and occupies Num.

In simple FGs, those composed basically of N, Poss and GDC, the latter remains in-situ (i.e. where it is base-generated) for there is nothing compelling it to move.10 For FGs involving modifiers, specifically APs,11 Ritter (1991) argues that they are NP-adjuncts, just like adverbs which are VP-adjuncts. They occupy the Spec positions of the head Ns as illustrated in (8b), and in this case, she also argues, (and prior to head N-raising to Num), šel-phrases can be right-adjoined to the top of the whole DP as roughly schematized in (8b).

(8)

a. ha-bayit ha-gadol šel ha-mora

the-house the-big of the-teacher

‘The teacher’s big house’

b. [DP [D ha- ][NumP [Num [bayit]i] [NP [AP ha-gadol ][N ti]]]]] [ DP [šel ha-mora ]]

In (8b), the šel-phrase, i.e. šel ha-mora ‘of the teacher’ is right-adjoined to the top of the tree. She claims that the right word order obtained is a result of N0-to-D0 movement in SNO word order (as the base word order in Hebrew nominals). This is based on some sort of parallelism between NSO, and SVO in the Hebrew clausal domain.12 She differentiates between subject–šel and object-šel FGs. The latter are illustrated in (9a & b) where the šel-phrase, i.e. šel dan (of Dan) follows the AP modifier.

(9)

a. ha-axila ha-menumeset šel dan et ha-uga

the-eating the-polite of Dan ACC the-cake

Dan’s polite eating of the cake’

b. [DP [D ha- ][NumP [Num [axila]i [NP [AP (?? menumeset)] [NP [DP šel dan ][N' [N ti][DP ha-uga ]]]]

There seems to be a problem in (9b), however. Ritter seems to eliminate et-phrase which means that she regards it as Accusative Case marker which is a feature of clauses (Pereltsvaig 2006). Pereltsvaig argues that in Hebrew nominals, the GDC has to be the external argument. The internal argument, she maintains, “is rendered as et-PP” which means that it has to follow rather than precede the AP modifiers. This is so because et in nominal domain is different from et in clauses. She agrees with Shlonsky (2004) that et in nominalization is a preposition “parallel to inherent genitive preposition šel ‘of’”, constituting what she claims to be et-PP as the internal argument of šel. Pereltsvaig considers “[t]he adjectival modifier in such nominals … [to] appear between the external argument and the internal argument (in other words, the internal argument, the (et-PP, follows rather than precedes the adjective)”( p. 14f).13

However, head movement has been viewed as theoretically and empirically inadequate, specifically under minimalism. The justifications that were provided in favor of head movement in the Principles and Parameters framework are lost under minimalist assumptions. For instance, Chomsky (2007) argues against D0 as the assumed landing site, which the head N is supposed to raise to. He makes use of the clausal domain predications, where V raises to the light v and tries to apply this to the nominal domain. He assumes that there is NP split in which a light n of nP c-commands N and that the head N raises to n in the same way V raises to v, and so “the structure is a nominal phrase headed by n*, not a determiner phrase headed by D, which is what we intuitively always wanted to say; and D is the “visible” head, just as V is the “visible” head of verbal phrases” (Chomsky 2007: 26).

In the clausal domain, for instance, it is characterized as violating certain principles of movements like the Extension Condition (EC) (see e.g. Chomsky 1995, Harley 2004, Boeckx & Stjepanovic 2001, Citko 2008, Roberts 2011).14 In addition, Roberts (2011: 196) argues that head movement is “subject to the standard well-formedness conditions applying to movement operations and their outputs generally.” Hankamer & Mikkelsen (2005) argue that word order ‘possibilities’ cannot be accounted for on the basis of such a movement. In contrast to Longobardi (1994), as noted above, Dimitrova-Vulchanova (2003) fails to use it in accounting for the facts imposed by Romance languages.15,16

In the nominal domain, specifically FGs, it is held that base-generating šel (or ћaqq) in a functional category, here D (or whatever a functional head), along with the Head Movement Constraint (HMC) (see Travis 1984), will block head movement. According to Sichel (2002, 2003), hadn’t the Poss šel imposed the blocking effect, head movement is preferred as ‘a last resort’ which is in line with Chomsky’s (1995) Economy Principle (EP). Sichel argues that covert movement is preferred to overt movement of full constituents once EP selects the least amount of material compatible with a convergent derivation. Some other linguists maintain that head movement is at least controversial (see e.g. Bruening 2009).17 Head movement also violates the Anti-Locality Constraint (ALC) (Abels, 2003: 12) schematized in (10).

(10)

[XP ….[X` [X Yi ][YP [Y` [ti ][... ]]]]]

Abels (2003) argues that ALC bans movements where a head X c-commands another head Y, in structures like (10), where it is not possible for the head Y to be attracted and adjoined to X due to resulting in an adjunction being too local. In addition, (Georgi & Müller 2010: 2) argue that head movement “as adjunction to the next higher head is incompatible with several well-established constraints on displacement.” They, in fact, propose that for head movement to be entertained, it has to be treated as reprojection. They argue that incorporating the concept of reprojection into the nominal domain would avoid “conceptual problems with head movement as adjunction.” In fact, a somewhat view has been held by Citko (2008) who proposes that to entertain head movement it should be conceptualized as projecting both internal and external merge operations. In the latter, an element projects the label, in the former the probe projects as structures.

Strong empirical evidence comes from the fact that head movement fails to account for the behavior of the Arabic indefinite article –n in SGs/CSs (see e.g. Shormani 2016a & b). If we assume, following Ritter (1991), that the head N raises to a head lower than D (Num, proposed by her), and since –n is base-generated in D, then we expect structures of the order D^N which is not possible. This could also be extended to Hebrew. The idea that Hebrew lacks indefinite article cannot be taken for granted that the head N can raise to a head lower than D (following the widely adopted assumption that ha- is base-generated in D) so that the resultant order is D^N. This is so because since Hebrew lacks indefinite markers (unlike Arabic), we cannot decide the absence of an indefinite marker, i.e. it might just be phonetically “invisible” (I return to this point in section 4). However, I propose here that head movement and EC could be reconciled by extending it to N-to-Spec movement (see e.g. Citko 2008, Matushansky 2006, Vicente 2007).

2.2. Remnant/Phrasal Movement

Based on Kayne’s (1994) antisymmetric linearization, some linguists argue for remnant movement as a substitution for head movement (see Ouhalla 2009, Koopman & Szabolcs 2000, Müller 2004, Wiklund & Bentzen 2007, Shlonsky 2004, Sichel 2002, 2003, Cinque 2003, 2005). According to Sichel (2003: 455), for instance, while head movement could be considered an option in CSs, one of the forces for remnant movement in the case of FGs is “the blocking effect imposed by šel.” This leads to proposing RM as a “movement of an XP which contains only X” (Shlonsky, 2004: 1484), but then this calls into question a serious problem, i.e. how is it that X, here, N, could move alone and D in FGs is not phonologically null?

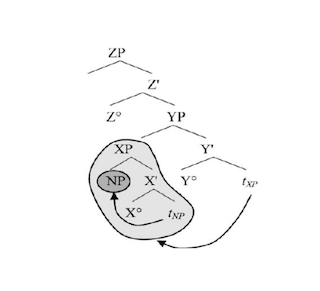

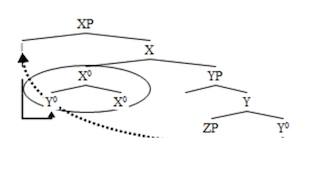

The RM proposed by Shlonsky and Sichel is not confined to possessive nominals, is actually a critique to N0-to-D0 movement in general. RM proponents argue that the nominal modifiers cannot be positioned by applying N0-to-D0 especially in nonconstructs. For instance, Shlonsky (2004) claims that only those heads, which do not assign Gen Case, can actually move. For modifiers, be they APs, numerals, Dems, etc., to be positioned in “the right of the noun, it is the noun phrase itself which has raised to the left of the modifier moving from specifier to specifier and pied-piping all the material on its right” in a successive manner. It is through such a fashion, he argues, “inverse or mirror image ordering of post-nominal material is accounted for” (p.1521). RM proposed by Shlonsky is schematized in (11) from (Pereltsvaig 2006: A4).

(11) is based on ‘‘roll-up’’ or ‘‘snowballing.” What happens in (11) is that the XP, along with the NP it contains, first raises from being Y0’s complement to Spec YP. The NP, then, raises to Spec XP. Second, it is not the NP which moves but rather the whole XP including NP. Third, it is not XP which moves but rather the whole YP, including XP, to occupy the Spec-ZP and so on in a pied-piping fashion.18

Sichel (2002, 2003) is perhaps the only one who applies remnant movement extensively to FGs. She argues that although head movement moves the least amount of material possible, remnant movement is triggered by some kind of violation to certain conditions, say, the potential violation caused by the presence of šel in D, which blocks head movement from N0 to D0. In other words, due to base-generating šel in D0 (or any other head higher than N0), head movement “fails to interfere with c-command and binding, since at no point do šel and its specifier form a constituent” (Sichel 2003: 455). In addition, she actually doubts the availability of head movement in multiple FG constructions like (12a) representing Hebrew from (Sichel 2003: 450) and (12b) representing YA.

(12)

a. ha-tmuna šel ha-xamaniot šel van gox

the-picture of the-sunflowers of Van Gogh

‘Van Gogh’s picture of the sunflowers’

b. al-muftaaħ ħaqq l-baab ħaqq s-sayyaara ħaqq ʕali

the-key of the-door of the-car ofAli

‘Ali’s car’s door’s key

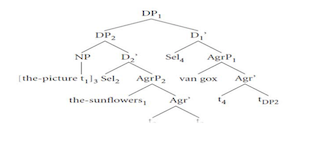

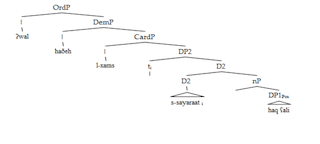

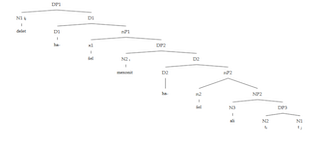

What is special to (12) is that there are two šel-phrases. In such multiple FGs, head movement fails to account for Case assignment/checking because unlike the clausal domain, in the nominal domain, Case assignment/checking is limited to a single Case checking position. Accordingly, structuring (12a/b) is determined by the numbers of the genitive elements it is composed of. Thus, a Hebrew FG as in (12a) consisting of two šel-phrases, namely šel ha-xamaniot and šel van gox, will include two DP-AgrP sequences to be able to check Gen Case of both complements. Sichel (2003) argues that head movement is an option but the blocking effect imposed by šel necessitates the phrasal movement option. For accounting for multiple Hebrew FGs like (12a), Sichel proposes (13) (from Sichel 2003: 457).

Omitting details, what happens in (13) is that DP2 the picture of the sunflowers undergoes a phrasal movement. It is actually attracted by Spec,DP1 and pied-piped to it. The same thing happens within DP2. The NP the picture (triggered by [+Def]) encoded in D2), first, undergoes a phrasal movement within DP2, from its base-generating position to Spec,DP2. This movement is actually forced by the presence of šel in D2. For how Gen Case checking takes place in (13), there is a DP-split. For instance, DP1 is split into AgrP1 which results in šel being raised from Agr0 to D0, where it checks von gox’s Gen Case. By analogy, the same thing happens within DP2. In addition, there is some kind of similarity between (13) and some English structures like Whose friend’s brother did you kiss? where the “[w]h-phrase specifier (embedded within a specifier) pied-pipes its DP” (Sichel 2003: 457). Such a proposal could be applied to Arabic multiple FGs as in (12b), though having three ħaqq-phrases, but not modified ones as will be clear later on.

This approach has, in fact, been rejected by some linguists for several reasons. For instance, Georgi & Müller (2010: 3) see it as relying “on a complex system of functional projections on top of a lexical projection”. This complexity goes against minimalist assumptions, arguing that remnant movement is difficult to deal with, because it does not contribute in finding out “whether NP-over-DP analysis can be maintained in the light of evidence for N displacement”.

Another problem the RM runs into is violating Abels’s (2003) ALC. As can be seen in (13) above, the movement the XP (along with the NP) undergoes from being a complement of Y0 to Spec-YP violates the ALC. The same violation happens when the NP moves from complement position to spec-XP as moving from a “complement to specifier position of the same head [X0] is banned because it doesn’t lead to feature satisfaction” (Abels, 2003: 12). Remnant movement, in addition, has been rejected by McCloskey (2005: 156ff), though he argues in favor of head movement in accounting for V-initial word order in Irish. He concludes that fronting hypothesis of the whole VP is not available in Irish VSO word order. He notes that even those V-initial languages are predicate initial but still nonheads should move before predicate fronting takes place.

Criticizing remnant movement, Pereltsvaig (2006: A2) maintains that in the clausal domain, remnant movement fails provide strong bases for accounting, among other things, for V-initial languages. Hence, she prefers N0-to-D0 to RM, ascertaining that if the latter cannot be applied in the clausal domain, it cannot also be applied in the nominal one. In fact, she criticizes Shlonsky’s analysis, holding that there are many problems still unresolved in this approach. Regarding the V-initial languages, she sides with Zwart (2003) who holds that head movement is more desirable for accounting for ultimate finite verbs. She sees head movement as not to be dispensed with, though her head movement (alternative to Shlonsky’s RM) is not like the classical head movement argued for in (Ritter 1987 1888, 1991, Borer 1996, 1999, Siloni 1991, 1997, among others). Rather her head movement is similar to Shlonsky’s tendency in a “roll-up” or “snowballing” fashion (Pereltsvaig 2006: A7). Like Georgi & Müller (2010), noted above, she maintains that RM does not account for FGs in a proper way because it requires many functional projections “dubbed” as (XP, YP, ZP, etc. and “whose semantic content is rather dubious.” Pereltsvaig argues that placement of internal-PP arguments is a more general problem (not considered in detail by Shlonsky himself), which concerns not only et-PPs in event nominalizations, but also šel-PPs, and a whole range of other argument PPs as well. She argues that Hebrew FGs like (14) are best handled in a “snowballing” head movement more than RM.

(14)

ha- tmuna šel ha-xamaniyot the-picture of the-sunflowers

‘The picture of the sunflowers’

To account for the derivation of (14), Pereltsvaig proposes the following argument: first, applying bottom-up derivation is due to the fact that šel-phrases are generated inside the lexical NP and θ-roles are checked at Merge on a par with Chomsky’s (1995: 313) postulation that “θ-relatedness is a property of the position of merger and its configuration.” Second, c-command relations are essential to accounting for et-phrases and all PP-internal arguments in general. She concludes that for Shlonsky’s proposed remnant movement to work accurately, the merged-inside-PP-internal arguments of an NP, including šel-phrases, have to exit such an NP before its raising in a remnant movement fashion.

3. N-to-Spec Approach to FGs

Though the analysis I am proposing here is minimalist in nature, N-to-Spec movement is not new (see Marantz 1984). It could be considered an extension to N-to-D, where the latter is reconciled with the EC (Matushansky 2006, Gebregziabher 2013, see also Citko 2008, Bardeas 2009), in the sense that while in N-to-D the head N movies from head position to another head position, in N-to-Spec the head N moves from head position to Spec position (Gebregziabher 2013).19

The minimalist nature lies in the fact that it makes use only of the primitive notions necessary to derive FGs. As such, it reduces the load placed on the human language faculty, by excluding the merger of the head N and the Def article from syntax. It also excludes the adjunction of a head to another head and satisfies several conditions and constrains on movement like EPP, ALC, etc. (I return to this issue below). In this approach, the head N raises to Spec,DP, which is followed by M-merger. M-merger merges the lexical head N with the Def article in the morphological component after transfer as a Spell-Out PF operation. The system proposed in this paper does not only account elegantly for simple FGs, but also for complex ones (I return to this issue in section 4.5).

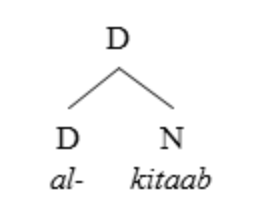

The apparent problem with this analysis is that it violates HMC. But this violation seems to disappear under eliminating bar levels (see Chomsky 1995, and later works). Chomsky maintains that a node can function as a head and a phrase, i.e. a minimal projection and maximal one, respectively, under two conditions: i) it does not dominate any more instances of itself, and ii) is not dominated by any instances of itself. This is obtained in (15), which satisfies both conditions:

The N kitaab in (15) satisfies both conditions. It is a head because it neither dominates any instance of itself nor is it dominated by any instances of itself. However, there are two Ds in (15) which, in principle, are different from each other with regard to position and hence, dominance. The upper D is a maximal projection because it does dominate an instance of itself, namely the lower D. The lower D is a minimal projection for two reasons: i) it does not dominate any instances of itself and ii) it is dominated by any instances of itself, and in this case, it is the upper D. However, eliminating the difference between maximal and minimal projections, as manifested in (15), does not mean we can move any category to any position. The process is rather controlled by other conditions and constraints. For instance, in the verbal domain, particularly SVO word order, the movement of DP-subject to [Spec-T] is triggered by T’s EPP. In the nominal domain, and particularly FGs, N-to-Spec movement is triggered by three factors: i), the blocking effect (Sichel 2003) of the DPoss as a structural barrier, ii) the EPP of the head D.20

Further empirical evidence comes from prenominal modification structures like (16). Before considering such examples, although there are several theoretical and empirical reasons that the definite article al-/ha- is merged in D, let us suppose that it is merged attached to the head N in N’s base-generation position, and that it moves up along with its modifiers. The question is: does the employed movement render a grammatical structure? Let us first see how structures like (16) are dealt with in remnant/phrasal movement.

(16)

l-xams l-muḥaaᵭraat l-ʔawala ħaqq t-tirm

the-five the-classes the-first of the term

‘The first five classes of the term’

Since Arabic is an (A-N) language (cf. Cinque 1996, 2003, Fassi Fehri 1993, 1999), modifiers, be they numerals, APs, etc. are merged as specifiers of the head N, (or say as specifiers of Functional heads to the left of the N), and, if they move in that order the order in (17a) is expected to result, and hence the ungrammaticality of (17a) resolved. It is implausible to postulate that prenominal modifiers originate simultaneously to the left and to the right of the head N. Supposing that such a “doubled directional modification,” exists, it is also implausible to postulate that modifiers to the left move while those to the right do not. Thus, such postulations are, in fact, theoretically and empirically problematic. If the head N (assuming it is merged with al- attached to it) and its modifier(s) move in RM, the structure in (17a) is expected whose derivation is schematized in (17b & c).

(17)

a.* l-muḥaaᵭraat l-?wala al-xams ħaqq t-tirm

the-lectures the first the five of the term

b. Baseline: [DP2 [D2 [ħaqq t-tirm [DP1[al-xams] [ l-?wala] [NP1[l-muḥaaᵭraat]]]]]

c. RM: *[DP2 [DP1[NP1 [l-muḥaaᵭraat]i [al-xams] [l-?wala] [DP1 [ħaqq t-tirm [ti]]]]]

RM, as manifested in (17), does not only render ungrammatical structures in terms of word order, but also it renders different ungrammatical and unexpected structures (just compare (16) to (17)).

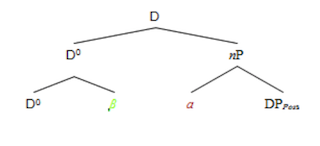

3.1. The proposal

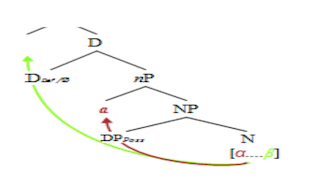

I propose that D in FGs has mainly two unrelated types: i) DDef/Ø and ii) DPoss (i.e. šel in MH or ħaqq in YA). Unrelated types because DDef/Ø concerns the (in)definite articles al-/ha- or Ø, and DPoss concerns Poss. In the former, if D has [+Def] feature, it will be DDef, and spelled out as al-/ha-. If, however, it has [-Def] feature, it is DØ and spelled out as Ø. The latter, i.e. DPoss is where ħaqq/šel is base-generated. Thus, in (18), α is the modifier, DPPoss Poss-phrase and β the head N. Thus, at the very point of merge, β is merged with α to its left, giving the configuration [α....β], and DPPoss is base-generated in Spec-NP. α will raise and land in Spec-nP, and β will raise and land in Spec,DP. By targeting and landing in Spec,DP, β satisfies EPP of D. For α to land in Spec-nP, it conforms to antisymmetrical left-movement (ALM, see Kayne 1994, see also Cinque 1996), hence, conforming to the Minimal Link Condition (MLC, see Chomsky 1995: 311, Fassi Fehri 1999: 106) and the Relativized Minimality (RelM, see Rizzi 1990). Thus, following Fassi Fehri (1999), I argue that α undergoes left movement to Spec-nP for creating minimal search space with D. The DDef/Ø will check its ɸ-features, [DEF] feature and all other features of the moved head N, as well as those of the AP modifiers, and the lower DPoss checks the Gen Case of the genitive complement. This is schematized and summarized in (18).

Regarding the possessor in (18), it remains in-situ for the fact that there is nothing compelling it to move because its every feature is checked by the DPoss in situ. Why [α....β], or otherwise [A-N], should occur in such a sequence is based on the assumption that Arabic and Hebrew are prepositional and not postpositional languages, hence, [A-N].21 However, it seems that there is a problem with (18), i.e. N-to-Spec produces DPs with [N-Def] word order, which is not possible in Arabic and Hebrew. For overcoming such a problem, I assume that there has to be a (re)merging operation affixing the articles into the head N.

3.2. The nature of Poss

That ћaqq is a DPoss has to do with the fact that from an etymological perspective, ћaqq is or denotes an ‘inalienable right,’ which is commonly found in Arabic expressions denoting inalienable rights. Almost the same thing is expressed by ћaqq’s varieties of Arabic as is illustrated in (19).

(19)

al-ʕaiš bi-karaama ћaqq li-kul ?insaan

living with-dignity right to-every human

‘Living with dignity is an inalienable right for every human’

Along these lines, Ouhalla (2009: 333) discusses the MA mata’ ‘property of’ exemplifying it in (20).

(20)

mta‘-i/al-makhzn

property-my/the-State

b. *had al-mta‘

this the-property

Ouhalla argues that mata’ “has an inalienable character insofar as it cannot occur in isolation from its possessor-argument” as the ungrammaticality of (20b) indicates. He also holds that the inalienable noun can also host a ‘possessor clitic’ as in (20a). Thus, he concludes that mata’ and its Arabic dialectal equivalents have the feature [BELONG]. This also holds of MA as illustrated in (21).

(21)

ћaqq-i ?an ?aʕiiš bi-karaama

right-my that live with-dignity

‘To live with dignity is my inalienable right’

The Poss ћaqq in (21) has an argument, i.e. the pronominal clitic–i. Like MA, ћaqq as an inalienable right cannot occur without a complement, as (22) shows.

(22)

a. *haðaa l-ћaqq

this the-property

b. *al-kitaab ћaqq

the-book of

Thus, I assume, following Ouhalla (2009), that ћaqq, like all inalienable nouns, inherently selects for an obligatory possessor argument. However, unlike Ouhalla, I assume that ћaqq has the feature [poss] encoded in DPoss.

As for Hebrew, though many studies (see e.g. Shlonsky 2004, Siloni 1997, 2003, Sichel 2000, 2003, among others), consider šel a preposition, and though there should be some evidence for the otherwise, I will assume that it has the feature [poss] like the YA ћaqq.22

3.3. M-merger

The remerging process referred to above is called m-merger, (morphological merger). M-merger can be understood as an operation which is part of the morphological component that merges the attracted head (i.e. the head N) and the attracting one (i.e. D), forming what is known as a complex head. Thus, following Matushansky (2006: 69), I assume that N0-to-Spec approach consists of two operations: “a syntactic one (movement) and a morphological one (m-merger).” This is roughly schematized in (23, from Shormani, 2014: 26).23

In (23), after N-to-Spec movement takes place, where Y0 targets Spec-XP, m-merger incorporates, or otherwise linearizes Y0 and X0 (as shown by the circle). However, it should not be confused with adjunction which is basically a syntactic operation, where a head adjoins to another. Rather, the configuration [X0 [Y0 X0]] is a result of a morphological operation taking place after transfer, hence no more a syntactic process (Matushansky 2006).

However, there seems to be some kind of violation to some minimalist assumptions due to the fact that m-merger involves a movement to a non-c-command position. I assume, following Matushansky (2006: 72) and Shormani (2014), that “[t]he landing site of head movement does not c-command the extraction site.” Moreover, if m-merger is no longer a syntactic operation, it, then, follows that the head D should not remain accessible in syntax. Matushansky argues that “M-merger must involve partial Spell Out of the resulting head; [A] head created by M-merger is a syntactic phase,” adding that after the complex head is formed, its internal structure gets frozen and “must involve Spell-Out as a subcomponent; that is, the head created by m-merger is syntactically opaque.” What Matushansky means by “syntactic opacity” is that the complex head created by m-merger is no longer accessible to any further operation as a “full” component. But rather, it is accessible as a subcomponent.24

Applying such scenario to Semitic FGs, the DDef/ /Ø will split into a complex head, consisting of DDef/ /Ø and β schematized in (23). After M-merger takes place, the result will be (24).

Compared to (23), what seems different in (24) above is that while in (23) Y0 is remerged to the left of the attracting head X0, in (24), the N will lower and adjoin to the right of the projected D. Taking this into account, and based on the nature of the affixes that can be incorporated into a head, I assume that m-merger in Semitic FGs takes the form in both (23) and (24) for three reasons. First, the theory of m-merger does not say anything about right adjunction, nor does it say that adjunction must be only to the left. Second, right adjunction has been applied to Chichewa language as shown in (25) below (from Vicente 2007: 23).

(25)

Mavuto a-na-umb-ir-a mpeni mtsuko

M SM.PST.mold.APPL.PERF knife waterpot

“Mavuto molded the water pot with a knife”

Third, conforming to Kanye’s (1994) LCA, I assume that there are three types of adjunction performed by M-merger: i) right adjunction, where D is the definite article al-, which is actually a prefix, hence, the N has to adjoin to the right of D, ii) left adjunction, where D is Ø. This Ø does not imply the absence of –n in indefinite FGs, but rather it is phonetically null, given the fact that –n is phonologically lost in Arabic nonstandard varieties, and because Hebrew does not have an indefinite article.25

3.3.1. Bareness of the head N

Some linguists (e.g. Shlonsky 2004, Sichel 2002, 2003) propose remnant approach to analyzing Semitic FGs based on the assumption that “the smallest lexical unit which is displaced is a XP, for example, NP” (Shlonsky 2004: 1466). What this means is that the definite article al-/ha- is base-generated attached to the head N, which implies that the head N is not bare in its base-generating position. If this is so, they claim, no N-raising (or head movement) applies, hence, proposing NP-raising.

What the above paragraph suggests is that for N-raising to apply (either in N-to-D or N-to-Spec), the head N must be bare. Thus, building on Vicente (2007), I argue that prior to N-to-Spec, the head N is bare. However, the question is what counts as a bare noun, or otherwise a bare head? A plausible answer to this question requires us to consider the head N in relation to inflections and the (in)definite marking. According to Vicente (2007), the concept of “bare head” comes as a result of the nature of ‘word’ where there is some kind of incorporation of more than one morpheme constituting the word in the morphological component. For instance, Vicente (2007: 24) analyzes the verb “a-na-umb-ir-a” in (8) above as containing complex heads, arguing that all the heads surface as suffixes to the root. For instance, take the suffixes i.e. –ir- and –a (the applicative and the perfective suffixes, respectively) which are suffixed to the root. However, other prefixes encoding tense and subject/object agreement, viz. a- and na- (representing agreement and past tense, respectively) are not taken to incorporate into the verb. She holds that every affix, be it a prefix or suffix, is base-generated in a functional head, and the verbal root is a lexical one. Like her, I assume that (in)definite article is not incorporated into the head N. However, unlike her, I assume that the head N is base-generated in N, having Case and ɸ-features’ inflections incorporated into it. In fact, my assumption is based on two aspects: i) inflections marking Case and ɸ-features are almost lost in YA and MH, except the plural inflection, which is even reduced to –iin marking all Cases,26 and ii) following the standard assumption regarding the bareness of the head N in construct states, I assume that the bareness of the head N of a FG is only related to (in)definiteness marking.27 Thus, if my argument is on the right track, it follows that what is incorporated by m-merger into the head N is only the (in)def article.

Another issue to be addressed in this regard is the necessity for the head N to raise to Spec,DP, and not possibly Spec-XP, or even X0 lower than D as proposed by Ritter (1991) in N-to-D approach. She proposes that in FGs, al-/ha- is base generated in D and the head N raises to Num (the head of NumP). In fact, theoretically, head movement violates several constraints on movements, specifically, under minimalist assumptions such as EC (see e.g. Chomsky 2001) and ALC (see Abels 2003).28

In fact, N-to-Spec movement is theoretically and empirically justified. Theoretically, for the head N to move to Spec,DP is motivated by: i) EPP of D, and ii) the ‘closest c-command’ (see Chomsky 2000) as a condition for Agree to take place. Empirically, head movement is blocked in FGs by the blocking effect of ћaq/šel in Dposs. If the head N raises to D while ћaq/šel in Dposs, Head HMC is violated. Another empirical justification for N-to-Spec movement is concerning indefiniteness marking (I return to this point below).

3.3.2. M-merger and Ordering

There is what I may call asymmetric linearization of (in)definiteness marking in Semitics. Semitics have two asymmetries, viz. D^N in the case of definite marking, and N^D in the case of indefiniteness marking.

Given the standard assumption that al-/ha- is base-generated in D, N-to-Spec movement would result in N^D which is not possible as the ungrammaticality of (26b) indicates.

(26)

a. ha-sefr šel ali

b. *[DP2 [sefri] [D2 ha- ]...[DP1 [D1 šel ][NP1 [ali ][N1 ti ]]]]]

Thus, m-merger or reordering is necessitated to render (24) grammatical.

c. [DP2 [D2 ha-[sefri] ]...[DP1 [D1 šel ][NP1 [ali ][N1 ti ]]]]]

Strong empirical evidence for N-to-Spec movement can be captured by the presence of the indefinite marker, i.e. –n suffixed to the head N as in (25), N-to-D, and/or even any other lower head, be it Num (Ritter 1991) or Poss (Fassi Fehri 1993, Kremers 2003), would result in D^N order which is again impossible in indefinite situations as is clear from the ungrammaticality of (27b) from standard Arabic.

(27)

a. kitaab-u-n li ʕali

book-Nom-Ind for/to Ali

Ali’s book’

b. *[DP2 [D2 -n ] [Num/Poss [kitaab-ui] …..[DP1 [D1 ħaqq ][NP1 [ʕali ][N1 ti ]]]]]

Thus, given our assumption that if –n is positioned in the head D, then, the expected position as the target of N-raising is a higher position, i.e. Spec, which must be higher than D. Thus, in both asymmetries of (in)definiteness marking, it seems that some kind of reordering or in Kanye’s (1994) terminology, i.e. linearization is needed. If this is true, it follows that m-merger is necessitated (among other things) to give us the desired order. Now, let us apply our proposal in (18, 23 & 24) to the derivation of (28).

(28)

al-bayt ħaqq ʕali

the-hous Gen Ali

‘The house belonging to Ali’

At the point of merge, the head N1 bayt (house) merges with the possessor ʕali ‘Ali’, forming NP1. NP1 merges with D1, i.e. the Poss ħaqq, forming DP1 which in turn merges with D2 al-. Now, D2 has [EPP] and [DEF] features unvalued. This makes it active and probes for a match. This match is found in N1 bayt ‘house’. The EPP of D2 (along with strong features) trigger the N1 bayt (house) to move to Spec,DP2. As a result of this movement, a limited search space is established between D2 and N1 bayt (house), and an Agree relation is established, where the unvalued features get valued and deleted. However, the Case feature of N1 bayt ‘house’ is still unvalued because it is assigned/checked by an external head. In addition, D1, in this case ħaqq, checks the Gen Case of the genitive complement ʕali ‘Ali’ in situ.

Thus, once all the possible features are checked/valued, the narrow syntax of (28) is schematized in (29).

(29)

[DP2 [N1 bayti] [D2 al- ] [DP1 [D1 ħaqq ][NP1 [ʕali ][N1 ti ]]]]]

The derivation in (29) above is followed by the m-merger operation in which the definite article and the head N form a complex head as illustrated in (30).

(30)

[DP2 [N1 ti] [D2 al- [N1 bayt] ….

In addition to the morphological necessity manifested by affixation, very empirical evidence for this m-merger operation is the phonological boundary, manifested in the assimilation process of al-/ha- into different types of sounds as can be seen throughout this article.

4. FG-Internal Structure

As is clear so far, the Semitic FGs consist minimally of a head N and a Poss-phrase headed by ћaqq/šel. Still, however, one needs to examine FGs having modifiers, be they pre- and/or post-nominal.

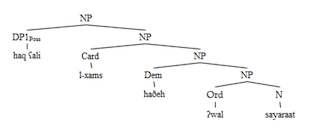

4.1. Premodifiers

Semitic FGs are known to exhibit premodification with quantifiers, Dems, numerals (and sometimes APs) (see e.g. Fassi Fehri 1993, 1999, Cinque 1996, et seq, Shormani 2014, Bardeas 2009, for Arabic, and Danon 2001, et seq, Shlonsky 1997, 2004, Pereltsvaig 2006, for Hebrew). For instance, quantifiers include kull/kol, baʕđ/kama, etc. (all and some, in Arabic and Hebrew, respectively), numerals include Cards like waaћid/wxad, ʔinaan/šnaim, etc. (one, two, in Arabic and Hebrew, respectively), Ords ʔawal/rišona, aani/šani, aali/šaloš (first, second, third, in Arabic and Hebrew, respectively) (Shormani 2014: 30).

The attested number of determiners is four and the order such elements can have in relation to the head N they modify is presented and exemplified in (31).

(31)

a. Q …> Dem …> Ord…> Card …>N

b. kull haðeh ʔawal xams sayaraat

all these first five cars

‘All of these first five cars’

Fassi Fehri (1999) argues that (31a) is the only attested order of determiners in prenominal position (see also Cinque 1996).29,30 No other combination is possible as is clear from the ungrammaticality of (32b) below (see also Fassi Fehri 1999, Shormani 2014).

(32)

a. Q …> Dem …> Card …> …>Ord…> N

b. *kull haðeh l-xams ʔawal s-sayaraat

All these the-five the-first the-cars

The ungrammaticality of (32b) has only one way out to explain; it has to do with scope relation. That is to say, there is direct hierarchical prominence observed by premodifiers: Q has scope over Dem, which in turn has scope over Card and so on. This seems to be a reflection of c-command effect observed by scope (see also Fassi Fehri 1999, Cinque 1996).

In applying remnant movement, Shlonsky (2004: 1478) claims that that in Hebrew, Ords can never precede the head N. Based on this, he argues that the head N cannot cross Ord, which is presumably one of the reasons for proposing remnant movement as an adequate “rival” to N-to-D movement. In Arabic, this is not the case; Ords can precede the noun or follow it. However, if Ord is syntactically indefinite (in the sense of having no al-) and all the elements are also syntactically indefinite, it can enter into such nesting manners (albeit not always). Take for instance, a three-element modification including Ord in (33).

(33)

a. Ord…> Q…>Dem…> N

b. ʔawal kull haðeh s-sayaraat

first all these the-cars

‘First of all these cars’

However, when Ord and Card are present in the complex, Ord has to be the first element and the Card must be definite. Consider (34) below.

(34)

a. ʔawal haðeh l-xams s-sayaraat

first these the-five the-cars

‘These first five cars’

b. *haðeh ʔawal l-xams s-sayaraat

these first the-five the-cars

What (34) implies is that Ord is always higher than Card, which means that the former always has scope over the latter. Now, let us consider the YA FG in (35), including the three premodifiers, Ord, Dem and Card, to see how the proposed analysis accounts for such structures.

(35)

ʔawal haðeh l-xams s-sayaraat ħaqq ʕali

first these the-five the-cars of Ali

‘Ali’s first of all these five cars’

In (35), the three determiners are ʔawal, haðeh and l-xams (first, these and the-five, respectively) premodifying the head N s-sayaraat. As has been stated earlier (see (18)), modifiers are base-generated as Specs to the head N they modify conforming to Multiple Spec Hypothesis (MSH, see Chomsky 1995, see also Kayne 1994, Cinque 1996, Fassi Fehri 1999). Now, given our conclusion regarding (34) above, when Ord and Card are present, Ord has to be the highest element in the surface structure. Thus, respecting, MLC, LCA and RelM, Ord will be base-generated closely to the head N. Since we have Card and Dem in (35), Dem will be base-generated higher than Ord and Card the highest (such ordering is outlined in relation to MIO in (section 4.3)). Thus, given this, the derivation will proceed as follows: at the very point of merge, the head N merges first with ʔawal, then, it merges with Dem haðeh and a third merge introduces l-xams into the derivation. The whole complex is then merged with the DP1poss. This is illustrated in (36a).

The NP is selected by nP, which in turn merges with D2 projecting into DP2. The definite article al- is base-generated in D2. The head N undergoes an N-to-Spec movement and lands in Spec,DP2, and the result is (36b).

DP2 is selected by Card projecting CardP to whose Spec the Card moves. CardP is in turn selected by Dem projecting into DemP the Spec of which will be the target of the Dem, and finally, DemP is selected by Ord merging with it and projecting OrdP whose Spec is the landing site for the Card ʔawal. The whole derivation process results in (36c). After all the narrow syntax operations take place, and after transfer, m-merger takes place, hence, merging the definite article s- and the head N sayaraat at PF. The result of all this is (36c).

4.2. Postmodifiers

It is a fact of Arabic and Hebrew (with a varying degree) that all modifiers examined in (section 4.1) can occur in postnominal positions in relation to the head N. In postnominal modification, the possible combination can be up to five elements as in (37).

(37)

a. al-kutub l-xamsa l-ʔawala haðeh l-jadiida kullahaa

the-books the-five the-first these the-new all-it

‘All of these first five new books’

b. *al-kutub l-xamsa l-ʔawala haðeh kullahaa l-jadiida

the-books the-five the-first these all-it the-new

Based on the ungrammaticality of (37b), I assume that (38) is the only possible sequence (order) of postnominal modifiers in relation to the head N they modify.

(38)

N…>Card….>Ord….>Dem….>A…..Q

4.2.1. Mirror Image Ordering

It has long been argued (see Fassi Fehri 1999, Cinque 1996) that Semitic APs exhibit MIO (albeit not always, see section 4.2.2) with the head N they modify. This is illustrated in (26) (compare MIO in Arabic in relation to English translation).

(39)

al-qalam l-fiđi ş-şiini l-ʔzaraq l-kabiir l-jaid

the-pen the-silver the-Chinese the-blue the-big the-good

‘The good big blue Chinese silver pen.

Consider MIO in Hebrew constructions like (40a & b) where (40a) is grammatical, but (40b) is not. The ungrammaticality of (40b) is ascribed to the fact that it violates MIO by placing the adjective denoting opinion yafim (beautiful) after the one denoting size gvohim (tall) (from Pereltsvaig 2006: A10).

(40)

a. psalim gvohim yafim

sculptures tall beautiful

‘Beautiful tall sculptures’

b. *psalim yafim gvohim

sculptures beautiful tall

In relation to English, and given (38-39), (41) is the possible MIO of AP ordering.

(41)

MIO: material…>origin…> color…>size…>opinion

MIO in (41) has been said to be available cross-linguistically. One more thing to note regarding AP base-generation position is that they are specifiers of NPs which “stems from the fact that their number is unlimited compared to complements. Based on antisymmetric linearization, and its algorithm, i.e. LCA, Kayne proposes (42)as a universal of the ordering of a Head (H), its Spec(s) and its complement (Comp).

(42)

Spec>H>Comp

In addition, Cinque (1996) extends Kayne’s (1994) antisymmetric linearization and applies it to Semitic DPs. He proposes that APs are Specs of NPs (see also section 4.3), let us apply our proposals to the FG in (30) where there are three APs, namely, l-waraqi, t-turki and l-jamiil modifying the head l-kitaab, and the Poss-phrase is ħaqq ʕali in (43).

(43)

al-kitaab l-waraqi t-turki l-jamiil ħaqq ʕali

the-book the-paper the-Turkish the-beautiful of Ali

‘Ali’s beautiful Turkish paper book’

However, note that in their base-generation positions, the order of the APs does not reflect MIO, they reflect the order of English, plus Poss-phrase. Let us call this base-generation order as outlined in (44), which is presumably the inverse of MIO.

(44)

AP Base hierarchical order

opinion…>size…> color…> origin…>material …> Head

where opinion has scope over size, which in turn has scope over color and so on.

However, the question is why do these multiple APs have to occur in that order in the base? A plausible answer to this question requires us to take into account two interrelated requirements: i) MIO and ii) hierarchical prominence. The former concerns their surface ordering in relation to the head N (I return to this point below), and the latter concerns their base. Recall from (section 4.1) that such hierarchical prominence is manifested in scope (which is in turn based on c-command). Thus, given the MIO in (41) and taking the base-generation into account, I assume that the most prominent AP must occur most closely to the head N as in (45) (read from right-to-left in relation to the head N).

(45)

al-jamiil t-turki l-waraqi kitaab

If our argument is true, the most prominent AP in this complex is the one denoting material l-waraqi followed by the origin t-turki and finally the opinion l-jamiil as illustrated in (46a).

(46 a)

Baseline: [NP [DPPoss [? ћaqq ʕali ]][NP [AP3 [l-jamiil ]][NP [AP2 [t-turki ]][NP [AP1 [l-waraqi ]][N [? kitaab ]]]]]]

As for how (46a) is related to MIO in the surface ordering can be captured by the minimal link formed by nPs. Thus, given MLC, ALM and RelM, it seems that there is not minimality violation (Shormani 2014, see also Cinque 1996, Fassi Fehri 1999). Given this, and taking a bottom-up derivation, the highest AP1 raises and lands in Spec nP1, AP2 in Spec-nP2 and so on, and consequently, the derivation will proceed as follows. The highest AP l-jamiil will move to Spec-nP1 (the first constructed FP), the lower AP, namely, t-turki will raise to Spec-nP2, and the lowest AP l-waraqi, i.e. will move and land in Spec-nP3, thus, giving us the desired MIO as in (46b).

(46 b).

AP-nP movement: [nP3 [AP1 [l-warqi ]][ nP2 [AP2 [? t-turki ]][ nP1 [AP3 [? l-jamiil ]][NP [DP [? ħaqq ʕali ]][NP [AP3 [l-jamiil ]][NP [AP2 [t-turki ]][NP [AP1 [l-warqi ]][N [? kitaab ]]]]]]]]]

Now, nP will merge with D projecting into DP. al- will be base-generated in D, and finally, the head N kitaab will move to Spec,DP2 for checking among other requirements discussed in (section 3), and the resultant structure is illustrated in (33c).

(46c)

N-to-Spec: [DP2 [N [? kitaab ]][D2 [D2 [al- ]][nP3 [AP1 [ l-waraqi ]][ nP2 [AP2 [ t-turki ]][ nP1 [AP3 [l-jamiil ]][NP [DP1Poss ћaqq ʕali ][N kitaab ]]]]]]]

As has been postulated so far, N-to-Spec takes place in the narrow syntax. However, the output structure is N^D which is impossible in YA and MH FGs. Thus, to obtain the D^N order, m-merger comes to play, and hence, (33d) is obtained.

(46d)

after M-merger: [D2 [D2 [al-kitaab ]][nP3 [AP1 [l-waraqi ]][nP2 [AP2 [t-turki ]][nP1 [AP3 [l-jamiil ]][NP [DP1Poss ћaqq ʕali ][N kitaab ]]]]]]

4.2.2. MIO Incompatibility

As seen above, it has been claimed that MIO is “strictly” reflected by AP ordering. Contrary to such claims, I argue that MIO does not always hold. In fact, there is a class of APs, what I call complex adjectives (CAs) which do not reflect MIO. CAs have complements and/or modifiers like the English related to others, different from others, interested in something, etc. (cf. Pereltsvaig 2006). Compare (47) to (48) below.

(47)

a. al-bint t-tawiila l-jamiila (MIO)

the-girl the-tall the-beautiful

‘The beautiful tall girl’

b.*al-bint l-jamiila t-tawiila (No MIO)

the-girl the-beautiful the-tall

(48)

a. al-bint l-jamiila l-ʔatwal min γair-eh fi l-ћafla

the-girl the-beautiful the-taller from other-her in the-party

The beautiful girl (who is) taller than others in the party’

b.*al-bint [l-ʔatwal min γair-eh] l-jamiila fi l-ћafla

the-girl the-taller from other-her the-beautiful in the-party

The APs l-jamiila and t-tawiila (the beautiful and the tall, respectively) in (47) are simple, and they strictly reflect MIO, hence the ungrammaticality of (47b). However, in (48a) the CA l-ʔatawl min γair-eh (the taller than others) makes MIO incompatible. In other words, the order of the APs [l-jamiila] and [l-ʔatwal min γair-eh] does not reflect MIO, but the (48a) is grammatical. This is clear from the ungrammaticality of (48b) which complies with MIO. This is also another piece of evidence against Shlonsky’s (2004) proposal of strict MIO (see Pereltsvaig 2006, for Hebrew counterexamples of Shlonsky’s claim).

In fact, examples like (48b) rule out remnant movement as a whole. In other words, if the head N raises along with [l-ʔatwal min γair-eh] first in a roll-up fashion, (48b) is expected. Along these lines, there are situations in which N-raising is favored, rather than NP-raising. For instance, Shlonsky provides (49) as empirical evidence that NP-raising cannot be dispensed with in Hebrew and Arabic.

(49)

a. ha- Volvo ha-xadas šel ʕali

the-Volvo the-new of Ali

‘Ali’s new Volvo’

b. *ha- Volvo šel ʕali ha- xadas

the-Volvo of Ali the-new

The ungrammaticality of (49b), Shlonsky argues, is due to the fact that ha-Volvo undergoes N-raising which seems to be possible. However, consider Arabic well-formed examples like (50).

(50)

a. s-sayaara l-jadiida ħaqq ʕali

the-car.F the-new.F of Ali

‘Ali’s new car’

b. al-sayaara ħaqq ʕali l-jadiida

the-car.F of Ali the-new.F

‘Ali’s new car’

Still, however, the optionality allowed by Arabic for both N-raising and NP-rising, unlike Hebrew, cannot be taken as evidence that NP-raising is a possible alternative. Put differently, if NP-raising is available in situations like (50), it seems not to be so in FGs like (51), where a relativized clause (RC), introduced by the Relative Marker (Rlm) ʔalli..

(51)

s-sayaara ħaqq ʕali ʔalli ʔištra-ha min ş-şiin

the-car of Ali that (he).bought-it from the-China

‘Ali’s car that he bought from China’

The possible derivation of (51) is schematized in (52a-c), representing the baseline as in (52a), narrow syntax as in (52b) and m-merger as in (52c).31

(52)

a.[DP2 [D2 [al [DP1 [ħaqq ʕali [NP1 [RCʔalli ʔištra-ha min ş-şiin] [N1 sayaara]]]

b. [DP2 [sayaara]i [D2 [al [DP1 [ħaqq ʕali [NP1 [RC ʔalli ʔištra-ha min ş-şiin] [ti ]]]

c. [DP2 [D2 [al [sayaara]i [DP1 [ħaqq ʕali [NP1 [RC ʔalli ʔištra-ha min ş-şiin] ti ]]]

However, if the head N along with its RC move as a unit, the resultant structure is not possible, hence the ungrammaticality of (53).

(53)

*s-sayaara ʔalli ʔištra-ha min ş-şiin ħaqq ʕali

the-car that (he).bought-it from the-China of Ali

Another strong piece of evidence comes from cases of modifications where the modifier is a PP as in (54a) schematized in (54b).

(54)

a. s-sayaara ħaqq ʕali min ş-şiin

the-car of Ali from the-China

‘Ali’s new car from China’

b.[DP2 [D2 [al [sayaara]i] [DP1 [ħaqq ʕali] [NP1 [PP min ş-şiin] [N1 ti]]]]]

But consider (55a), schematized in (55b), where the head N (along with its PP modifier) undergoes NP-raising (or phrasal movement).

(55)

a. *sayaara min ş-şiin al- ħaqq ʕali

car from the-China the of Ali

b.*[DP2 [NP1 [PP min ş-şiin] [N1sayaara]i [D2 [al [DP1 [ħaqq ʕali [NP1 [ti]]]]

As can be seen in (55b), the result of this movement is an ungrammatical structure, not only in terms of word order concerning the head N and PP modifier, but also concerning that of the head N and the definite article al-.

Let us even suppose that the definite article al- is merged attached to the head N (constituting one unit, as assumed by Shlonsky) and that it originates within NP1. Given the assumption that modifiers originate as Specs, if the whole NP moves as a unit, the result is (56) which is again ungrammatical, lending us strong evidence against remnant movement and in favor of our proposal.

(56)

*min ş-şiin al-sayaara ħaqq ʕali

from the-China the-car of Ali

Given the assumption that modifiers of an X are base-generated as Specs of X, it follows that in the case of YP (as a modifier of X), which itself has modifier(s) (i.e. Specs), Y has to undergo Y-raising independently form its modifier(s). Let us consider (57), where the AP itself is modified by an adverb.

(57)

al-xabar l-jamiil fiʕlan

the-news the-good surely

‘The surely good news’

In (57), the adverb fiʕlan (surely) is base-generated in the Spec of AP l-jamiil (the good), and if this is true, it follows that the apparent occurrence of the AP l-jamiil before the adverb is derived by raising the AP per se to a higher position. This gives rise to postulating that APs must raise over (past) adverbs. However, if they move with adverbs, the structure in (58a) is not persevered, and if the whole complex, i.e. the head N, AP and adverb are in FGs, the resultant structure is (58b) which is impossible.

(58)

a. *al-xabar fiʕlan l-jaid

the-news surely the-good

b. *al-xabar fiʕlan l-jaid ħaqq l-jauum

the-news surely the-good of the-today

To conclude this section, it seems that N-to-Spec movement overcomes several problems encountered by the existing approaches like N-to-D and remnant movements. Though interesting and valuable, it seems that such approaches need to be rethought so that they could account for the ungrammatical structures in (54-58). In this article, I have reconciled N-to-D with EC by extending it a step further to include such examples. In this point, I would like to mention an interesting study done by Pereltsvaig (2006), where she modifies remnant movement, but again, she employs head movement such that the head raises in “a snowballing” fashion to a head, though there are certain things I do not agree with her, I am not in a position to tackle them here any further. What I want to suggest here is that whatever approach we employ, such an approach should account for most of the actual data relating to it. Another issue to examine our proposal in relation to is multiple FGs, and whether it accounts for the syntactic and (possibly) semantic properties of such constructions.

5. Multiple FGs (MFGs)

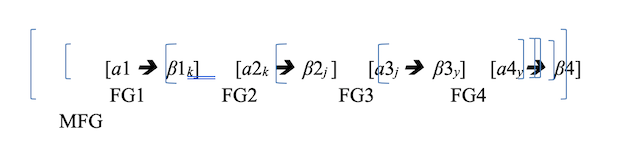

In this section, I apply the analysis I am proposing to multiple FGs in MH and YA, claiming that the proposed analysis is compatible with, and provides a straightforward and principled account for such constructions. Multiple FGs are constructions having more than one FG such that one or more FGs are embedded inside a matrix one, similar in a way or another to CPs (i.e. matrix clauses). One particular property specific to multiple GFs is that there is some kind of a double functionality a constituent in FG does, forming a chain of functions. In other words, an embedded head N can function as a genitive complement of a preceding head N and a head of a succeeding one. Let us call this Double Functionality Head-Complement Chain (DHC) which is schematized in (59) (cf. Shormani, 2016).

Where a is the head N of a FG and β is its genitive complement (i.e. DPposs) and è symbolizes the genitive relation expressed by Poss in IHC.

IHC is manifested in multiple FGs as a relation such that the head N of the first DPposs functions as the head of the succeeding DPposs. This is indicated by the indices k, j and y. For instance, β1k functions as the genitive complement of a1, and as a2k (head) of β2j, indicated by the index ‘k’. This is also true of other βs. Now, consider (60a) and (60b) from YA and MH, respectively.

(60)

a. al-baab ħaqq s-sayyara ħaqq ʕali

b. ha-delet šel ha-mexonit šel ali

the-door of the-car of Ali

‘The door of Ali’s car’

Let the DP-head be a and the DP-GDC β, then a functions as the head of β. In a multi-embedded FG, then a1 functions as the head of β1 (= FG1). It follows that β1 will function as a2 for β2, and so on. In terms of Set Theory, there seems to be an intersecting relation among such FGs. This relation could possibly be expressed through the intersection formula in (61a), which in turn can be generalized as in (61b):32

(61)

a.FG2∩FG1=β1

b. FGn∩FGn-1= β n-1

To simplify the whole process, let us use two metaphorical relations: “father to” and “son to” in the way Arabic proper nouns given in a name of a person operate, which could be analogized with embedded heads in a multi-embedded FG. Consider the name of a man in (62).

(62)

Ali Saleh Naji

In (62), there is a name consisting of three proper nouns, Ali, Saleh and Naji. Ali functions as the son to Saleh, Saleh functions as a father to Ali and a son to Naji. This means that Saleh has a double function, i.e. as a son once, and a as a father once more. However, Ali functions only as a son and Naji functions only as a father. Let the set {Ali, Saleh} be FG1 and the set {Saleh, Naji} be FG2. It follows that the intersecting member in FG1 and FG2 is Saleh. Let Ali be a1, Saleh β1 and Naji β2. This is similar to the intersecting relation expressed in (61) above.

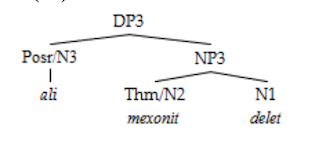

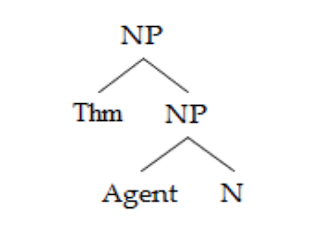

Reconsidering our proposal so far (see 18), I think it needs some sort of modification to account for multiple FGs. In multiple FGs, I assume that the head of the nP, i.e. n, hosts the Poss, i.e. ħaqq/šel, and its Spec hosts postnominal AP-modifiers. For deriving multiple FGs like IHC, and in line with Chomsky (2000, 2001), I propose that nP could suffice, and there is no need for the projection AgrP (if it is merely proposed for housing APs and checking Gen Case of GDCs). I assume that such FGs consist of multiple nP layers, and every nP layer is introduced by a DP layer (wherever needed). Now, looking at (60b), we are likely to find multiple FGs consisting of two FGs having three DP constituents: ha-delet, ha-mexonit and ali ‘the door, the car and Ali, respectively’. Syntactically, each of these DPs has a different function from the other two. For instance, delet functions as the head N of the matrix FG (a1) in (59)), mexonit functions as both a genitive complement of the preceding head N, namely, delet and a head N of the genitive complement ali (hence β1), and ali in turn functions only as a genitive complement (hence β2). However, from a semantic (thematic) perspective, each carries a different q-role: Possessor (Posr)…>Theme (Thm) …>N, where delet is the head N, mexonit is the Thm and ali is the Posr.

Given this, I assume that in their baseline position there is an asymmetric c-command relation relating one to the other. However, whether this asymmetric c-command relation is to be preserved in their surface is not clear at this point (cf. Sichel 2002). Now, let us assume that there are two independent options of ordering in the baseline position: i) Posr>Thm>N, or ii) Posr>N>Thm. In the former, N>Thm>Posr is derived by leftward movement of Thm over Posr to a higher embedded Spec, and the head N will raise to the highest Spec, namely, Spec,DP (i.e. of the matrix). In the latter, however, N>Thm>Posr is derived by rightward movement of Posr+N (as proposed by remnant movement, see Sichel 2002) over Thm. However, the latter is not tenable with the proposed analysis for two reasons: i) rightward movement is excluded from our proposal because this violates Spec>H>Comp adopted here, and ii) if we assume that Posr is a specifier to the head N and Thm is its complement (and if so, (see the syntactic function of mexonit, taking LCA into account, i.e. Thm is linearized to the right), it follows that Thm movement is not necessary in order to derive the correct (surface) word order.

Contra these views, I assume that the three DPs in (60) will have the baseline structure as Posr>Thm>N for three reasons: i) word order is not the only requirement for the head N and/or Thm to move to a higher position, ii) if syntactic objects are linearly unordered as maintained Kayne’s (1994) antisymmetric approach that a syntactic structure is left branched, then there can be no such thing as base-generating to the right of the head, and iii) in minimalism, complements (here Thm) are introduced by a first Merge, which means that complements are antisymmetrically merged as left objects. Nevertheless, specifiers of the same head are introduced into the computational system by a subsequent Merge, again, to the left. Given this, I assume here that the surface linear order is a result of both internal merge (see Citko 2008a & b), i.e. the head N undergoes internal merge to Spec,DP, and m-merger merging the head N and the Def article, as a PF operation. Given this, the three DPs in (60b) will have the baseline structure as Posr>Thm>N. Let the head N of the matrix be N1, Thm N2 and Posr N3, constituting DP3 as illustrated in (63a).

In line with the proposal in (63a), and following Chomsky (1995, 2000, 2001), I assume here that there is no need for AGR projection once there is a simple (but elegant) alternative (unlike in Sichel 2003).33 The alternative is nP whose Spec hosts moved AP modifier(s) and the head n houses the Poss šel. Let this nP be nP2 which is selected by D2 ha-, merging with it, and projecting into DP2. This is illustrated in (63b).

In (63b), the Thm mexonit raises to Spec,DP2 first in equidistance movement (cf. Fassi Fehri 1999) which conforms to RelM, MLC and EC. Empirically, however, this movement is motivated by the fact that the Thm (i.e. mexonit) functions as a genitive complement to the head N delet, and also as a head to the Posr ali, hence, N-to-Spec is not violated. In addition, this movement will not violate HMC because the movement involves moving a constituent from a specifier position to another specifier position. Now, the question is does Spec-nP constitute a potential a-governor (in Rizzi’s sense, i.e. say, A Spec) target for Thm to move to it? An answer to this question is that since, as assumed so far, movement in the developed proposal must have a trigger (i.e. a feature F e.g., say, [DEF]), and since D is the only head carrying such F (among other strong features), I assume that the head n being filled with the Poss šel does not trigger Thm’s movement to its Spec, and hence RelM is not violated, neither is MLC, as stated above.

Now, DP2 merges with n1 projecting into nP1. In this point of merge the second šel is introduced (i.e. base-generated) into n1. nP1 merges with D2, hence, projecting into DP1. Thus, everything being equal, the head N delet raises to Spec,DP1, and hence, satisfying first EPP of D1 and second RelM because trace (as an empty category) in Spec,DP3 does not affect RelM, and so, I assume traces do not block the head N of the matrix FG to move to Spec,DP1. This is illustrated in (63c).

Prior to me-merger, the Thm mexonit’s Gen Case is valued by šel situated in n1. Note that the Posr ali remains in situ, for some reason (I return to this below). At this point in the derivation, it seems that every operation required by syntax has been performed. However, still, linearization has to take place, incorporating the definite article ha- into both mexonit and delet in D2 and D1, respectively. The result of all this is a phrase marker demonstrated in (63d).

Thus, in (63d), and prior to m-merger, the Thm and the head N raise independently to Specs (DP2 and DP1, respectively), allowing for different feature checking/valuation like ɸ-features, Def and Case. Thm is ɸ-complete; its Gen Case feature is valued by šel. Def and ɸ-features enter the derivation valued, but those of D2 are not. As a result an Agree relation is established between them, the result of which is valuing all unvalued features of D2. The head N delet is also ɸ-complete, its ɸ-features are valued but those of D1 are not, hence, Agree relation is established between them and all unvalued feature are valued. However, it has an unvalued (interpretable) Case feature whose valuation (and interpretation) depends on an external head (T, v, or P). Thus, once it enters into an Agree relation with this external head, it gets valued.

Thus, as postulated in (18, 23 & 24), it seems also that even in multiple FGs, the Posr does not move. In (63d), for instance, the Posr ali remains in its in-situ position (cf. Sichel 2003). In Agree system, the Posr’s features are valued in situ, because Agree can take place at a distance; there is no reason compelling Posr to move.

It seems that the baseline structure in (63a) accounts for the order in which the three elements (Thm, Posr and N) occur. However, it is also clear that we could account for the point raised above regarding the relation among the three constituents in their surface structure in terms of which (asymmetrically) c-commands which in their surface structure. It is clear, as shown in (63c), that the head N asymmetrically c-commands Thm, which in turn asymmetrically c-commands Posr (cf. Kayne 1994: 17ff.).

The question is: does the order concerning Posr>Thm>N proposed here apply to Agent>Thm>N? In fact, no. Contra Sichel’s (2003) assumption of asymmetric binding and scope, I show here that her analysis (though valuable and interesting) fails apply to Arabic while my analysis applies to both Arabic and Hebrew. Sichel proposes that in structures like in (64a & b), Thm is base-generated to the right of the head N (from Sichel 2003: 451), and raises in remnant movement leftward to Spec,DP of the matrix FG.

(64)

a. ha-tmuna šel rina šel acma

the-picture of rina of herself

‘Rina’s picture of herself’

b. ha-tmuna Šel acma Šel rina

the-picture of herself of rina

‘Rina’s picture of herself’

Sichel argues that the reflexive acma (herself), i.e. Thm carries a Theme q-role in both (50a & b), regardless of the order, and that the name Rina carrying an Agent q-role c-commands the Thm (i.e. the reflexive). In other words, she argues that binding asymmetry is not affected by the order of genitives in Hebrew. However, it seems that her analysis is not compatible with Arabic. Consider the multiple FG (65a) and (65b).34

(65)

a. ş-şuura ħaqq ʕalia ħaqq nafs-haa

the-picture of Alia of self-her

‘Alia’s picture of herself’

b.*ş-şuura ħaqq nafs-haa ħaqq ʕalia

the-picture of self-her of Alia

(65b) is not possible in Arabic while (65a) is, because in (65a), ʕalia c-commands the reflexive nafs-haa since it is in its binding scope while nafs-haa in (65b) is not in the binding scope of ʕalia because it does not c-command it. This actually makes it clear that c-command and structural dependency required for binding is maintained in Arabic. Thus, if we assume, as claimed by Sichel, that the name ʕalia, i.e. Agent c-commands the reflexive nafs-haa, i.e. Thm, regardless of the order, how can we account for the ungrammaticality of (65b)? If the order of Thm and Agent has no effect in Hebrew, it does have effect in Arabic. To account for the ungrammaticality of (65b), I assume that in the base, Agent does not c-command Thm, rather it is Thm which c-commands Agent, and to obtain the correct word order, it is the Agent which raises while Thm remains in situ. This also conforms to our postulations that Thm is always base-generated to the left of the head N in both N>Thm>Posr and N>Agent>Thm, and not to the right of N as claimed by Sichel. Thus, reconsidering (63a-d) above, in N>Thm>Posr, it is the Posr which c-commands/binds Thm, Posr does not move while Thm does. However, in N>Thm>Agent, the behavior of the constituent does differ, i.e. it is the Thm which c-commands Agent, and consequently, it moves while Thm remains in-situ.

My assumption above stems from the fact that scope effect is not merely confined to Thm as bound pronouns or reflexives, but it also includes nominal Thms. For instance, in (66a & b) Thm is not a reflexive, i.e. Thm is a nominal DP l-qaria ‘the village’ and the Agent is ʕali ‘Ali’. In this case, Thm c-commands Agent in the base, and Agent per se raises as in (66a). If, however, Thm raises it renders the structure ungrammatical as in (66b).

(66)

a. ş-şuura ħaqq ʕalia ħaqq l-qaria

the-picture of Ali of the-village

‘The painting of the village by Alia’

b.* ş-şuura ħaqq l-qaria ħaqq ʕalia

the-picture of the-village of Alia

Based on our argument above, I claim that the orders Posr>N>Thm and Agent>N>Thm are not in free variation, but rather each order has its own behavior. While Posr>Thm>N is a possible alternative order of multiple FGs, Agent-Thm-N is not, but rather Thm>Agent>N, where scope and c-command are respected. Thus, I propose that for FGs having N>Agent>Thm, the baseline structure is (67).

The baseline structure in (67), in addition to accounting for Hebrew, provides empirical support to our claim that Thm cannot be merged to the right of the head N, but only to its left. This is actually one of the empirical stakes the proposed approach comes up with, and hence surpassing other alternatives such as head and remnant movements.

Further, that modifiers do move independently of the head N they modify is borne out. However, there remains something to be addressed here, i.e. the analysis developed here provides a straightforward account for the ability or degree of N-raising in Arabic and Hebrew FG structures as in (68), where the head N in Hebrew cannot cross CardP while Arabic ones can.

(68)

a. al-muħaađaraat l-xams l-?wala

the-lectures the-five the-first

‘The first five lectures’

b. al-xams l-muħaađaraat l-?wala

the-five the-lectures the-first

‘The first five lectures’

c. ?wal xams muħaađaraat

first five lectures

‘First five lectures’

(69)

a. šaloš rišonot simfoniot

three first symphonies

‘First three symphonies’

b. šaloš simfoniot rišonot

three symphonies first

‘First three symphonies’

c.*simfoniot šaloš rišonot35

symphonies three first

As clear in (68), the head N in Arabic can raise crossing both OrdP and CardP as in (68a), crossing OrdP as in (68b) and crossing none as in (68c). However, in Hebrew the head N raises and crosses only the OrdP as in (69b). Thus, in Arabic the head N has three options represented in (68a-c) while in Hebrew it has only one option, which is raising and crossing only the Ord as in (69b). This is also clear from the ungrammaticality of (69c). This also gives us room to account adequately for why premodifiers occur in the order Card….>Dem…>Ord in their baseline (but not in any other order)- in Hebrew the head N cannot cross CardP. This is also another piece of evidence that the head N has to raise independently of its modifier(s) which the analysis proposed here accounts for adequately and elegantly. An interesting conclusion can be drawn here: even very closely related languages (like Arabic and Hebrew) may differ in some typological issues like the behavior of the head N-raising.

6. Conclusion