Introduction

The audience is considered the main actor in media communication as it is the primary recipient of media and communication operations Consequently, it has garnered significant interest from both media and marketing researchers, who approach and view the audience from different perspectives. The growth of advertising and its impact on the development and survival of media organizations have imbued the media audience with a consumer character, as audiences have become the primary financiers of various media outlets Thus, the audience is defined both as a product of the media and as a product of the advertising industry, effectively seen as a consumer group.

Given the overlap and importance of the audience as a receiver for both media organizations and advertising institutions, and the extent to which the concept of the audience is linked to the advertising industry, the audience is critically viewed from different angles that all converge on considering it as a consumer to be managed using market logic The audience is thus seen as a means in the hands of advertisers, to the extent that its behavior can be directed and manipulated

Before reviewing these new approaches, we will first provide an overview of the concepts of the audience as a product of the media and the approaches to the audience as a consumer within the context of consumer culture.

1. Operating concepts

1.1. Audience as a Product of the Media

In Media Studies, the term ‘audience’ refers to a group of people who engage with the media. According to the Larousse Encyclopedic Dictionary, the audience is defined as

“the activity of positive listening, attention, and interest that the audience shows to the person who is addressing it. The audience can be commercial, civil, or penal ; it is the act of listening to a person and showing interest.1”

The Dictionary for Library and Information Sciences defines ‘audience’ as “the people who read a literary work or attend an artistic performance”2, distinguishing it from the ‘target audience’, which represents the people to whom the writer, creator, publisher, or producer intend the work.

Another definition refers to the audience as

“the various groups of people interested in a particular form of media, such as readers, listeners, viewers, spectators, or consumers. This concept also includes measuring the audience’s exposure to the media.”3

It is possible to find several concepts related to the audience, such as the Public and Users, especially in the context of new media where interaction and usage play a significant role.

2.2. Audience and Public

We find many meanings associated with the term audience, such as the term public. Although many media dictionaries do not distinguish between the Latin terms public and audience, in Arabic4, it is necessary to clarify the difference between the two.

The conventional meaning of the term public distinguishes it from what pertains to private groups. It refers to a large number of individuals who share general interests and engage in common cultural practices. This shared interest fosters a sense of unity, albeit varying among different publics. British scholar Sonia Livingstone defines the public as :

“A shared understanding of the world, a common identity, an expectation of engagement and mutual understanding toward a collective goal ; it involves open and transparent discussions in which members participate to affirm or challenge this shared understanding, identity, values, and interests” (Livingstone, 2005).

For researchers in sociology, defining and controlling the concept of public proves challenging, except in its relation to other social practices like watching movies, visiting museums, or engaging with institutions (Dewey, 1927). Within the heterogeneous nature of most audience types, despite shared interests among their members, some audiences exhibit specificity due to the distinct characteristics of their members. Thus, the audience is also considered

“That part of society whose members grasp the intentions of a particular author (sender), the intricacies of a textual structure, or a cultural product, such as the audience for certain types of contemporary music and theatre” (Abercrombie & Longhurst, 1998).

This perspective aligns with the positive view of the audience, contrasting with negative definitions within media studies that often critique mass appeal as inherently negative. This negative viewpoint is prevalent in the sociology of cultural industries, linking the audience to the reception and reputation of entertainment content, which inevitably shapes the composition of its interested audience (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1944 ; Hesmondhalgh, 2019).

Therefore, it is preferable to use the term the sociology of reception to refer to the research field concerning public issues. This concept is advocated by many researchers for developing a methodology that emphasizes situational dependency. Chinese cultural studies professor Ien Ang describes this dependency as

“the necessity of examining the contexts that shape audience practices rather than focusing solely on individuals’ media experiences and behaviors”. (Ang, 1991)

People tend to

“consciously devote cognitive effort to specific types of media messages, such as television, newspapers, the Internet, or social media. Exposure to these media and the attention given to them can significantly predict changes in behavior and social action.” Ang defines the concept of actual audiences as “infinite sets of practices and experiences that cannot and should not be confined to any system of knowledge.”

In the realm of mass media, it is often assumed that the masses equate to the public or society as a whole. This dual identity of the public traces back historically to the emergence of print media, which fostered a sense of common interest among elite members during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Habermas, 1989). The initial conceptualization of the public centered around these elites,

“who served as prototypes for democratic organization and a framework for understanding broader public formations during the era of electronic media, encompassing those likely to engage with literary, musical, or cinematic creations” (Thompson, 1995).

In the mass media environment, the public is defined as the specific audience for each medium, which is a completely different meaning of the term public. The study of an audience of a particular medium involves examining its specific audience, such as newspaper readers, radio listeners, television viewers, moviegoers in a cinema, pedestrians exposed to advertising posters, or users of new means of communication. (McQuail, 2010)

Publics are usually characterized by their large size, physical separation, and heterogeneity. Examples include the audience of readers, the audience of listeners, the internal audience, and the external audience. Therefore, the importance of the audiences that senders are targeting can be classified according to the degree of their identification. These audiences can either be indefinite, composed of unknown individuals who have no other common feature at a specific time than the spatial field in which they are present (such as a district, a city, or a coverage area), or they can be clearly defined and relatively homogeneous, with individuals linked by a specific social or personal identity (Dayan & Katz, 1992).

From this point of view, we can describe those who belong to the specific audience of a TV channel as people who have watched this channel for a period of at least four hours distributed over five to seven days during a week, for example. For newspapers, a reader is considered anyone who personally read or skimmed through the paper during a reference period, typically corresponding to the publication’s issuance cycle (daily or magazine), regardless of how they accessed it. Through a study focused on precisely defining and determining the characteristics related to the audience of each medium, the audience becomes an identified core that is of significant interest to advertisers (Napoli, 2011).

This leads us to discuss the questions raised by the concept of audience as a quantitative measurement.

2.3. Audience as a Quantitative Measurement (related to Exposure)

Some researchers believe that the audience represents the active dimension in the field of audiovisual communication and corresponds to readability in the field of written communication. Consequently, differences in the analysis of exposed audiences arise from the varying measurement processes, leading to the consideration of the audience concept in terms of exposure to audio, visual, and written media.

Regarding this numerical or quantitative view, the audience represents the diverse groups likely to be interested in a communication medium, including members who are enumerated as consumers, listeners, viewers, spectators, or readers of this medium.

The Media Dictionary defines the term ‘audience’ primarily in numerical terms as

“a measure of the number of users of an electronic media service, such as the number of viewers or listeners, or the number of surfers visiting various websites.”

It is also defined as

“the number of people who watched or listened to a television or radio program, measured by centers and opinion polling through samples and automatic measurement techniques.”5

If we revisit Livingstone’s analysis of the concept of ‘audience’ in media research, we find that she aims to reveal the importance of demographic and social characteristics in explaining aspects of personal practices and experiences with the media. According to her analysis, the concept of ‘audience’ refers to two different meanings :

-

The narrow meaning : This refers to the group of people who are expected to be exposed to the content provided or broadcast by the media and the number of those who are exposed to it.

-

The exhaustive meaning : This refers to the echo of the messages being received and the extent of interest that the medium generates. This meaning aligns with the previous definition of the public.

The tremendous development in communication technology has made the constant search to identify the characteristics of each media audience a key challenge since the end of the last century. The first meaning of audience, defined as a numerical measure associated with exposure, has become predominant and is now the primary focus of interest for both media professionals and advertisers alike.

The concept of audience as a quantitative aggregate is therefore closely tied to the concept of exposure, which has become dominant today and is of significant interest to professionals in the media and advertising fields6 This concept emerged from the advertising industry’s market-driven logic, stemming from the use of media as platforms for advertising. It arose from the necessity to measure and quantify viewership, listenership, and preferences—a key challenge in understanding audience behavior and preferences.

The concept of audience as a quantitative measurement is therefore gaining significant importance in the media community, particularly for sectors reliant on advertising and sponsorship for financing. In the Western world, and even in some Arab countries, television and radio have adopted relatively credible audience measurement tools (like Audimat), with industry-wide acceptance. However, measuring internet exposure has not yet achieved a stable level of credibility, as it still fluctuates based on various criteria such as visitor numbers, page views, and even click-through rates7

The development of audience measurement was largely unaffected by the cultural approach in audience research. Its foundation remained primarily commercial, particularly with the rise of marketing and commercially driven media organizations. Despite the expansion of media exposure analysis and audience quantification, researchers often overlooked the social and cultural changes in the evolving media landscape. Simultaneously,

“advertisers and consumers began expecting more than what traditional audience exposure models could provide, emphasizing the need for data linked to consumer interaction crucial for making immediate sales decisions.”8

“What matters within the quantitative concept of audience measurement is the frequency of interaction (or contact) between media and their users, as expressed in ‘opportunities to watch or listen’ (OTV/OTL)9”

This discussion underscores the public’s engagement with commercial products, governed by market logic that typically prioritizes transactional outcomes over the deeper connections that products may forge with their audiences.

3. Modern Approaches to Public Use of New Media

From contemporary perspectives on the public in the new media era, there is significant discourse surrounding the evolution of ‘public’ as a concept, encompassing a range of new phenomena and ideas. This evolution has spurred the development of novel approaches to audience research, aimed at understanding emerging patterns of media consumption within the evolving media landscape.

3.1. From the Audience to the User

The transition from “Audience” to “User” in the new media era reflects a profound evolution in how we interact with content. Traditionally, the audience was passive, consuming content created and distributed by a few authoritative sources (senders). However, with the rise of interactive technologies and platforms, users now have the capability to produce, distribute, and consume content themselves. This shift empowers users to not only consume but also actively participate in creating and sharing content with others. It blurs the distinction between sender and receiver, fostering a more dynamic and participatory media environment where users play a crucial role in shaping the discourse and influencing the content landscape.

This evolution marks a significant shift from the traditional model where authors (senders) created content for passive audiences. As distinctions between creators and consumers blur, audiences become active participants, challenging traditional notions of the audience as passive recipients, and instead emphasizing engagement, interaction, and participation in virtual spaces. Over time, this trend could indeed lead to a conceptual shift where the term “audience” may diminish in relevance compared to the more inclusive and participatory term “users” in the digital and interactive media landscape. This evolution highlights how technology is reshaping our roles and relationships within media environments10

3.2. Audience and Content Production

Indeed, in contemporary media organizations, there’s a profound interplay between content creation, communication strategies, community engagement, and the active involvement of users. This dynamic reflects a significant shift from the traditional role of the audience as passive observers to active participants in the virtual world. Users now not only consume content but also contribute to its creation, share their perspectives, and interact with others in digital communities. This transformation has redefined how media organizations operate, emphasizing the importance of user-generated content, feedback loops, and community building as integral components of their strategies. As a result, the relationship between media producers and consumers has become more interactive, collaborative, and participatory, shaping the evolving landscape of the digital age11

Based on this, some researchers describe media institutions as having become gatekeepers in a narrow sense. Indeed, Philip M. Napoli believes that media have come to produce little of the content, but rather act only as gateways through which audiences cross to reach the content12

3.3. The User-Generated Content

Given the development of the concept of the audience, the position of the receiver has shifted from merely being a receptor or recipient of media content to becoming a producer and distributor of it. This vision is particularly applicable to the new media landscape, in which the concept of the audience has evolved, producing new phenomena in individuals’ relationships with these media.

From this perspective, many researchers have been interested in exploring the dimensions of the emergence of so-called ‘User-Generated and Distributed Content’. This discussion has focused significantly on the ability of users to distribute rather than produce content. Some researchers believe that “the phenomenon of consuming online media content and redistributing it has become a shared social experience in contemporary consumer culture.”13

What defines Web 2.0 is that users have become an integral part of the production and consumption process by collecting content through publishing, writing, and sharing. Indeed, some studies predict that 70 % of the content available on the internet is produced by users, in what is called User-Generated Content (UGC)14

4. Audience as Consumers

With the growth of consumer culture and the advertising industry, we witness the profound influence of marketing studies on cultural ideas, introducing numerous concepts from marketing research into sociological and media theory, particularly those related to consumer behavior. Discussions about consumer culture and society begin in the 1960s with the concept’s emergence, pioneered by George Katona, a specialist in consumer psychology. At that time, society and media are less complex compared to today’s global economy and digital age. Consumer culture encompasses more than mere products or spending ; it reflects an economic system comprising institutions, values, and beliefs that promote consumer behaviors. Consequently, shopping is now viewed as a remedy for various psychological issues and a source of psychological stability, self-affirmation, and identity15

The foundational models for studying audiences as receivers of media content intersect with those explaining audience behavior as consumer groups. Audience and consumer research are interconnected due to their shared focus on the masses consuming media products or being targeted by advertising. French scholar J.M. Décaudin argues that within organizations, the concept of audience, closely tied to the effective reception of media content, forms the basis for institutional communication. Décaudin advocates that effective institutional communication hinges on a thorough understanding of the receiver, enabling messages to be tailored accordingly. This understanding requires ongoing monitoring of the sender-receiver relationship to consistently evaluate feedback received after communication messages are delivered.16

Consumer theory often straddles both structural and subjective explanations. Therefore, the tradition of consumer research in academic marketing is divided into two research paradigms : positivist and interpretive approaches.17 The positivist approach emphasizes rational consumption choices (the economic view), while the interpretive approach, or culturalist approach, focuses on the influence of cultural and social factors on consumption choices, which may not always be rational.

4.1. Positivist Approaches

Before the emergence of consumer orientation, consumers are viewed as passive spectators receiving one-way communication, representing a target group predetermined by organizations. Marketing seeks to move away from this traditional perspective by emphasizing respect for the consumer-customer. Marketers make significant efforts to gather opinions and values, aiming to uncover consumer trends and understand their lifestyles.

The consumer is now seen as an individual whose desires and needs are constantly reassessed, with data linked to their attitudes being continuously collected and organized. Databases are systematically enriched with audience and consumer knowledge, used to design products and services. This approach aims for personalized interactions to foster a two-way communication relationship between consumers and organizations, departing from the traditional one-way model. Positivist approaches, which emphasize rationality, continue to dominate studies on consumption and purchasing behaviors.

4.2. Interpretive Approaches

The interpretive paradigm critiques the objectivist (positivist) view and advocates focusing on personal symbolic experiences. It posits that meaning is a social, cultural, and historical construct, emphasizing the diversity in consumer experiences.

Within this interpretive paradigm, many researchers align with radical marketing thought, drawing from social and cultural studies, social constructivism, qualitative methodologies, and post-structuralist and postmodern theories. They critique mainstream marketing and consumer research for its reliance on empirical objectivity, arguing for greater methodological and epistemological diversity. According to them, objective marketing research often overlooks the political dimensions inherent in quantitative research practices.

Stuart Hall, an influential Jamaican-born British cultural theorist and a key figure in Reception Theory, is renowned for his development of Encoding and Decoding theory. He argues against the notion that audiences passively accept media content. Instead, he emphasizes the audience’s active role in negotiating and contesting cultural meanings within a dynamic model. This approach to media audience research, rooted in cultural theory, aims to diminish the gap between message creators (encoders) and receivers (decoders).

Consumer research is also influenced by cultural ideas from anthropology, semiotics, and sociology. Marketing imports the majority of its analytical techniques from behavioral sciences. However, there is limited consideration given to the introduction of many concepts from marketing research related to consumer behavior into sociological and media theory. For instance, concepts such as the Self-Reflective User, Segmentation, and Target Groups permeate the fields of media and cultural studies, becoming fundamental ideas in the sociological discourse on media use.18

The interpretive approach, which emphasizes the complexities of meaning expressed through symbols, language, and social interactions, also influences marketing studies. Consumer research draws inspiration from modern structural theories, reception studies, ethnography, and structuralism.

In the 1980s, there is a notable shift in focus from broad influences to localized and culturally distinct groups within mass media studies. This marks a significant change in research paradigms, acknowledging that audience research alone cannot fully elucidate the cultural meanings embedded in media texts, highlighting the limitations of the mass society debate.

Meanwhile, the development of audience measurement and exposure analysis continues independently of these cultural approaches in audience research. A crucial aspect of contemporary discourse on mass media is the resurgence of the concept of the mass audience, driven by commercial imperatives in marketing and media organizations. This emphasis on commercial audience measurement often overlooks the social and cultural transformations shaping the media environment.

The interpretive trend ultimately struggles to reconcile the cultural complexities of mass society, viewing it as comprised of diverse groups with heterogeneous identities rather than as an expression of unified national culture. Concurrently, advertisers and consumers increasingly demand more than what traditional audience exposure models can deliver, emphasizing the importance of data linked to consumer interactions for making immediate sales decisions19

4.3. Modern Views of the Consumer

The relationship between economy and culture plays a crucial role in shaping consumer culture, leading to criticisms regarding the lack of dialogue between these two traditions. Debates emerge about the extent to which advertisers can exploit and control consumers, representing the opposing poles of sociological and philosophical discussions on the relationship between agency and structural influences (or self-management) in consumer audience studies.20

Modern perspectives on the consumer celebrate their freedom of choice, contrasting with the social approach that depicts them as culturally manipulated by advertising. Dominating psychological studies of consumption, the cognitive-emotional approach focuses on the structure of perception, memory, and trends, significantly influencing customer-oriented marketing studies over the past three decades.

These diverse views of the consumer can be classified as follows21 :

-

The Social Approach : The social approach views the consumer as heavily influenced and controlled by the advertising industry. Advertising is perceived as a tool that manipulates and exploits consumer vulnerabilities, dissatisfaction, and psychological frustrations. In this perspective, the consumer is portrayed as culturally naive, guided by behavioral cues, and susceptible to advertising influence. Criticisms of this approach encompass concerns ranging from content and ethical issues to ecological impacts.

-

The Emotional Approach : The emotional approach draws on psychological studies of consumption and presents a more nuanced perspective compared to the social approach. Advertising is viewed as a tool that serves a demonstrative function, with professionals reducing overt manipulation and control of consumers. Instead, there is an emphasis on addressing consumer needs and desires, including unconscious ones, focusing on the structure of perception, memory, and values. This viewpoint has significantly influenced customer - oriented marketing studies over the past three decades.

-

The Liberal Approach : This approach glorifies the idea of the free consumer and the sovereign shopper when engaging with television programs or encountering advertisements. It promotes the idea of the consumer as a creative individual and self-reflective thinker, celebrating their freedom of choice. This perspective serves to legitimize the prevailing ideology of consumption and seeks mechanisms to understand consumer characteristics, opinions, values, and needs. According to this liberal view, collecting organized data, particularly about lifestyle standards, is crucial for feeding databases. There is a continuous search for both quantitative and qualitative knowledge to design programs within personalized customer relationship marketing, aiming to build a two-way communication relationship between the consumer and the organization.

-

The Social Responsibility View : Some prefer to focus on the consumer’s responsibility, rather than viewing them as victims of the advertising industry. For instance, American economist Milton Friedman asserts that “Advertising does not break the critical spirit ; instead, consumers’ tastes are declining.” He believes that excessive involvement in advertising policies through irrational consumption stems from the fact that we are not merely spectators in the advertising game ; we are partners who voluntarily or involuntarily agree to it.22

-

The Schizophrenic Audience : Some researchers question the nature of today’s audience, caught between activity and passivity. They describe the audience as schizophrenic, characterized by :

“The audience that lives in a highly mediatized world, marked by dispersion and commercial control, where comprehension, understanding, responding, and restoring meanings and contents broadcast through the media are almost impossible. Today’s public is divided ; it enjoys democracy and freedom but also suffers from domination and control.”23

-

Audience and Compassion Fatigue : Many professionals, whose business success depends on public engagement and responsiveness, are concerned with mechanisms for reactivating and revitalizing the public. Philippe Henon, Director of Communications and Press for UNICEF Belgium, emphasizes that this issue has become increasingly relevant, particularly for activities reliant on societal and civic engagement in social and public communication. He notes that civil society organizations are struggling to engage and educate the public amidst the rise of natural and technological disasters. Henon argues that professionals must study new phenomena related to the current audience, such as “compassion fatigue,” which he describes as :

“Excessive and increasing exposure of the public to images of human suffering. This overwhelming exposure to content depicting violence, discrimination, or inhuman behavior diminishes the capacity to mobilize feelings, empathy, and humanitarian responses. Public participation in giving and organizing donations is vital to finance and support activities, making it essential to address this challenge in public communication strategies.”

4.4. The Audience as a Consumer Target Group

The previous analysis indicates that contemporary perspectives on the consuming public tend to exalt the rational view, which emphasizes agency and responsibility. However, the constructivist cultural view reinforces the idea of the audience’s power. This creates a conflicting situation between these two perspectives, sparking controversial academic debates. The resolution to these questions seems to emerge from the third stage of cultural studies within the constructivist theory, which views the audience as discursive constructs and knowledge as socially constructed. In this theory, many concepts and approaches have become common in both media and marketing dictionaries, forming foundational ideas in the sociological discourse on media use. This has produced a modern perspective that sees the public as a targeted consumer group.

This is a realistic and utilitarian vision based on the principle that advertising is a fundamental dimension of consumer society. Communication efforts must be tailored to the characteristics of the audience, not only their demographic traits but especially their lifestyles, which include various attributes, social behaviors, and cultural patterns, as well as their media exposure. In the new media era, the concept of mass personalization has emerged and developed, focusing on gathering data and insights about different audiences to target them effectively at the lowest cost.

The concept of the audience as a targeted consumer group is defined by the differences that distinguish various consumer groups. Organizations aim to classify customers into homogeneous units of analysis, known as market segments, which are groups of customers with similar desires for a specific product. These groups also share a set of characteristics related to their consumption behavior.24

This term has a special meaning in the field of advertising and is of great importance because the effectiveness of the communication strategy depends on segmenting and targeting the audience based on their exposure habits. In media and communication, it has become statistically possible to identify this audience and consequently target a niche audience—a segment of a brand’s main audience with very specific needs and interests.25

To a large extent, this concept is a modified version of the traditional notion of ‘audience’, wherein organizations view audiences through their media practices, interactions, and group dynamics. As such, audiences are identified as relatively homogeneous groups, committed to visual culture content, with individuals often associated with a particular social or personal identity.

Advertisers are particularly interested in these audiences, striving to attract them by understanding and interpreting the meanings individuals assign to their relationships with others and with the medium.26

From this perspective, critical views of the audience emerge within the advertising industry and consumer culture, where audiences are often perceived as commodities or products.

5 Audience Commodity or Audience Product

This idea, put forth by American political and media economist Dallas W. Smythe27, argues that the media economy revolves around selling audiences to advertisers. This concept links the notion of the audience closely with the advertising industry, leading to the audience being perceived either as a product or as a means. In today’s prevalent consumer culture, we observe a shift from viewing individuals as viewers to viewing them as consumers. This shift is evident in the common use of the phrase ‘consuming media products’ rather than ‘receiving media content,’ implying that media messages are treated as commodities to be marketed to the consuming masses28

Some researchers view the audience as the most important product or valuable asset produced by advertising-based communication. Philip M. Napoli supports this perspective, describing media audiences as “the primary product manufactured and sold by the media to advertisers.”29 According to Napoli, in the process of selling audiences to advertisers, media

“treat the audience as a product, primarily quantifying public attention to media content and, to a lesser extent, the embedded advertising messages.”30

In her ethnographic perspective on the television audience, Ien Ang examines audiences critically in her renowned book Desperately Seeking the Audience, portraying them as media products manipulated by cultural industries. She scrutinizes television’s pursuit of an audience, viewing audiences as controlled “masses”.31

In her examination of television culture, Ang provides new insights into the media landscape and scrutinizes television’s desperate search for an audience. She argues that as media organizations transition towards market orientation, they increasingly monitor and conceptualize the audience by quantifying and commodifying it. This approach constructs the audience as a measurable commodity that can be sold.32 From this perspective, all media content—whether news, entertainment, or educational—is primarily a vehicle to attract and retain larger audiences, aiming to capture their attention and loyalty.33

5.1. Implications for the Media Industry

The concept of the “audience commodity” has significant implications for the media industry. Eminent American professor of communication studies James Webster acknowledges that media industries often reduce people to one-dimensional members of a target market or assign them value on a ‘cost per thousand’ basis. This perspective reflects how media organizations categorize audiences primarily as statistical units for advertising purposes, rather than considering their complexity as diverse and multi-faceted individuals with varied interests and perspectives. This reductionist approach underscores the commercial nature of media operations, where audience segmentation and monetization strategies often prioritize demographic metrics over holistic understanding.

This perspective aligns with Dallas Smythe’s critique, which argues that audiences are bought and sold based on their consumption habits and capabilities, treating the media audience as a “commodity” or market segment manufactured and sold by media organizations supported by advertisers.

Smythe identifies three primary entities governing today’s media market : the media institution, the advertising institution, and the advertising agency. These entities work to integrate the audience (as receivers across every medium) with the consuming masses (as consumer markets). Therefore, the fundamental mechanism of the media economy is facilitated by two types of markets and two types of products :

-

The first stage begins with the media organization selling a media product (such as a TV channel, magazine, or movie) to a market represented by diverse masses with varying needs, desires, and preferences. The masses purchase the media product, thereby generating revenue for the media institution by selling audience attention to advertisers. This makes advertising a primary source of income.

-

The second stage involves the media product attracting a specific audience—for instance, a magazine or website capturing the attention and interest of a particular group of individuals. To attract and retain large and specific audiences, media companies tailor their content to appeal to advertisers’ desired demographics. This audience is then identified, defined, and sold to advertisers.

5.2. Implications for the New Media Environment

We have outlined the two stages shaping the traditional media market. This perspective has evolved in the new media environment into the concept of the Three-Sided New Media Market, which typically refers to the complex interplay among three main entities or groups within the digital media ecosystem. These entities are34 :

-

Media Institutions or Platforms : These include entities like social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram), video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube, TikTok), news websites, and other digital content providers. These platforms produce and distribute content that attracts users. They leverage user data to tailor content recommendations and optimize user engagement. Their functions include content production and distribution, user data collection, and the monetization of user engagement through advertising, subscriptions, and other revenue models.

-

Audiences or Users : This group comprises individuals who engage with various forms of media platforms. They consume content such as articles, videos, images, and social interactions. Their functions include consuming media content, generating valuable data through their interactions, and content creation, especially on platforms that support user-generated content (e.g., YouTube, Instagram).

-

Advertisers : Advertisers are businesses or individuals who pay to display their advertisements on digital media platforms. Their functions include implementing advertising campaigns, reaching and influencing audiences or users through targeted advertising based on demographics, interests, and behaviors, and generating revenue by paying for ad placements and other promotional activities.

5.3. The Dynamics of the Three-Sided Market

Technology has opened new doors and provided the ability to monetize a marketplace from three sides instead of two. In fact, we are now witnessing a new generation of marketplaces that are rapidly increasing their market share, called ‘three-sided marketplaces.35‘

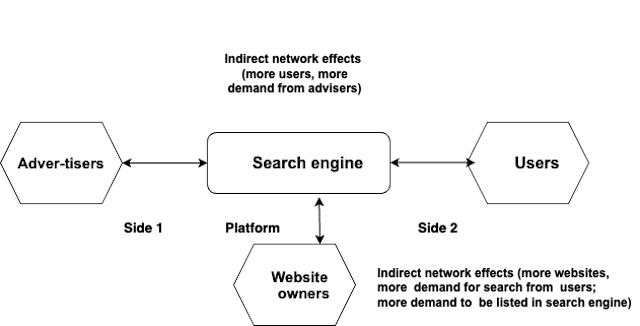

The three-sided new media market uncovers the interconnected relationships among three ‘players’ : new media platforms or website owners, users, and advertisers. The interaction among them creates a dynamic ecosystem based on generating revenue and attracting large audiences, shaping the production, distribution, and monetization of digital content36

The concept of the audience commodity has distinct implications for the new media industry, which encompasses digital platforms, social media, streaming services, and other internet-based media. New media platforms monetize audience attention through advertising revenue and subscriptions. The commodification of audiences allows platforms like Google, Facebook, and YouTube to offer “free” services by selling user attention and data to advertisers.37

This may be illustrated in the following scheme

Three-sided New Media Market38

To maximize audience commodification, companies employ cross-platform strategies (e.g., Facebook owning Instagram and WhatsApp), consolidating user data to offer more precise ad-targeting. Advertisers pay for access to targeted audiences, leveraging user data to optimize advertisement placement and effectiveness. This personalization is a direct result of treating the audience as a commodity. Platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter thrive on user-generated content, commodifying the audiences that follow and interact with this content. They optimize their interfaces and content to maximize user engagement and encourage frequent interaction.

6. The ‘Work’ of the Audience

Among the many analyses viewing the audience as a target product, Dallas Smythe’s ideas about the ‘work’ of the audience stand out. In his influential proposal that first considered the media audience as a “means” manufactured and sold by media outlets supported by advertisers, Dallas Smythe introduced the concept of audience ‘work’ to describe what the media produces and the active engagement of audiences in consuming media content. He argued that audiences are not passive recipients but actively contribute their attention and engagement, which media organizations then monetize by selling audiences to advertisers. This concept highlights how audience behavior and interaction with media content generate value that supports the economic model of media industries. Smythe elaborates :

“Since the power of the public is produced, sold, bought, and consumed, it calls for a price and therefore it is a commodity. Just like any other labor force, it includes work. The act of consuming or using the media represents a form of wageless labor in which the public is involved for the benefit of advertisers.”39

Dallas Smythe justifies this idea by stating that the work of the public involves learning the patterns of buying consumer products and spending money accordingly. In short, they work to produce

“the demand that advertisers need.” Other researchers, focusing on television, argue that audience members, who are compensated by gaining access to the programs they watch, become a valuable asset to the programmer. Through their viewing, the programmer can convert viewing time into additional advertising revenue.40

The work of the new media audience is also evident in the activities of marketers and advertisers, who prioritize consumer input when designing their strategies. They develop new approaches that encourage consumers to participate in the marketing process, effectively doing the work of marketers and advertisers in defining and designing advertising messages. Additionally, they integrate consumers into product marketing through various forms, especially by encouraging discussions about products and their advertising messages in online forums and social media conversations.41

Many researchers have expanded on Dallas Smythe’s concept of audience work, adopting the idea of describing the audience as audience labor. Some researchers question how television networks use new media developments to effectively exploit and sell the audience’s work to advertisers in response to the proliferation of channels, the growth of the internet, and the rise of ad-blocking technology.42

Despite the wealth of data produced by new media, the concept of mass communication and ‘audience work’ has not garnered sufficient interest. Nevertheless, the emergence of new media platforms has significantly blurred the traditional boundaries between producers and consumers, empowering audiences to engage with content in diverse and interactive ways. The concept has languished somewhat over the last three decades, but the new dynamics of mass communication—particularly with the advent of new media and the evolving role of receivers as mass transmitters—prompt a reconsideration of the relevance and usefulness of the ‘work’ of the audience today.43 In fact, there is a shift towards viewing the public primarily as consumers rather than citizens. Audiences are often perceived as users and products, essentially serving as unpaid contributors to media institutions, which in turn monetize this audience data by selling it to advertisers.

Conclusion

As we conclude this article, it becomes evident that the transition from viewing audience engagement merely as an outcome to commodifying audience attention represents a significant paradigm shift. In today’s dynamic media landscape, researchers focus on exploring how new media technologies redefine the concept of audience participation. Central to this exploration is the recognition that modern media environments empower audiences not only as passive receivers but also as active participants who can create, share, and shape content.

As a result, the meanings of the audience as recipients of media content and as targeted consumer groups have begun to overlap and harmonize into a unified concept within the media research lexicon. Today, the audience is more clearly defined as both consumer and product rather than solely as citizens receiving information. This shift underscores a fundamental change where audiences, equipped with digital tools and platforms, can influence narratives, amplify messages, and cultivate communities around shared interests. The ability of audiences to act both as receivers and transmitters in this digital ecosystem highlights the interactive and participatory nature of contemporary media consumption. Academic research has also shifted toward focusing on the masses as media consumers, reflecting the dominance of consumer-driven culture.

The consequences of viewing the audience primarily as target consumers rather than as informed citizens require thorough examination, particularly in contexts like ours where media production lacks both quantity and quality. In such environments, the content created and shared by new media users often becomes the primary alternative. Traditional media in these regions increasingly rely on user-generated content to structure their programming schedules. This practice has become prevalent as a means to ‘enrich’ traditional media offerings.

However, media should strive to understand their audiences to produce content that genuinely meets their needs, addressing and resolving issues of interest. This approach is crucial to prevent media from being entirely driven by promotional concerns and to ensure they fulfill their original mission of addressing society’s diverse social and cultural challenges.