Introduction

The observation of the Algerian linguistic landscape before the 2022 official decree referring to teaching English in primary schools and giving it a more prominent role in the present linguistic landscape reveals that English has been expanding steadily and quietly, gaining larger use domains since the 2000s. For example, it can be noted that English is increasingly used in public spaces with commercial signage (Nakla, 2020; Maraf and Osam, 2022) and other expressions of linguistic landscapes. Typically, the expansion of English is linked to globalization, whose most prominent aspect is the economy. But a closer look at the situation in Algeria may reveal rather unexpected facts. Despite a proclaimed and budding liberalism in Algeria, the relatively long tradition of ostracism casts its shadows over the liberal volitions. The Algerian market is barely open due to multiple economic restrictions. Algeria has set barriers to slow down economic globalization through the implementation of limitations on the free market and free exchange. This situation deter big commercial brands from investing in the market despite potential demand. Likewise, the Algerian job market does not seem to make the mastery of English a real asset for job seekers. However, these facts do not match how the linguistic landscape evolves. It could be claimed that the internet is the game changer in this linguistic shift. A catalyst for change in many societies, the internet has transformed people’s lives in personal and communal spheres. New jobs and new forms of communication and expression have emerged where English has a dominant role. The internet is playing a crucial role in this slow but concrete linguistic transformation, especially through the tremendous impact of social media used by millions of people worldwide (Belmihoub, 2018). This situation brings to the surface another fundamental question that will be addressed concerning the type of English being promoted: What is the significance of the English variety spreading through social media and other unofficial routes in the current global context?

The present study was undertaken to explore these issues and weigh one aspect of English use in Algerian society. It seeks to gain insights from the analysis of some marketing tools which can help evaluate the role and place of English outside educational settings. It also aims to evaluate the role of bottom-up linguistic practices and see whether they follow the direction of the official language policy.

1. Theoretical Background

Linguistic practices cannot be observed or analyzed in isolation from other related and impactful factors. A systemic approach to comprehending the processes involved in such practices is fundamental. As language and society are inextricably entangled, knowledge in history, economy, politics, and sociology may help explain to profane and non-national readers the underlying linguistic mechanisms operating in any setting, notably in Algeria.

At the local Algerian linguistic level, Tamazight and Arabic are two languages which have been sharing centuries of coexistence and have undoubtedly influenced one another. Tamazight is present in several Berber varieties (e.g., Kabyle, Chenoui, Chaoui, Targui, etc.), while Arabic has two distinct forms, namely Classical Arabic and Algerian/Dialectal Arabic; these two forms of Arabic have separate roles in society and are unequivocal depictions of diglossia as depicted by Ferguson in 1959. Currently, Arabic and Tamazight are both national and official languages.

As far as external linguistic influences are concerned, French still has a prominent role in Algerian society. The French colonial presence for over a century forced the admission of French into the Algerian linguistic legacy. After Algeria’s independence in 1962, the French language obtained a special status, becoming more than a foreign language but slightly less than an official second language. In the educational sphere, it is regarded as the first foreign language. Regarding English in Algeria, it is unambiguously a foreign language ranked second after French. However, the increasingly rapid transformations imposed by globalization may lead to other outcomes in the short or mid-term. The growing use of the internet in Algerian society may bring about profound changes that were unexpected in the near past. The internet has become a surrogate for traditional media, especially for young people. The premises of a linguistic shift are already apparent (Belmihoub, 2018).

In this context, learning a foreign language and making use of it may result from different types of motivation, mainly intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Brown, 2000). There is, however, a grey area where this categorization becomes unclear. Prospective English users, for example, have the widest array of reasons to learn this language, and English learning and use have an undeniable added value no matter the extent of its significance. Known as the language of globalization, English can equally be learned to perform a song or a role for an international audience or to have the opportunity to publish in most scientific and academic journals in the world. Phillipson (1992) summarizes the role of English in the world as follows:

English has a dominant position in science, technology, medicine, and computers; in research, books, periodicals, and software; in transnational business, trade, shipping, and aviation; in diplomacy and international organizations; in mass media entertainment, news agencies; in youth culture and sport, in education systems, as the most widely learned foreign language. (Phillipson 1992, p. 6)

Firstly, the technical and scientific value of English is ubiquitous in all fields of research. English is the language of science par excellence (Tardy, 2004; Drubin and Kellogg, 2012). This situation resulted from a variety of circumstances, among which is the technological decline of Germany after WWII and the massive migration of scientists and researchers to the west coast of the Atlantic (Hasman, 2004). Foyewa (2015) surveyed the role of English as a language for science and technology in various countries and academic and research institutions. The results yielded by this investigation showed, with no surprise, the dominance of English as a vehicular language, which explains the unprecedented rush to learn this particular language. To meet the growing demands for the teaching and learning of English for technical and scientific purposes, a sub-branch of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) emerged, known as English as an International Language for Science (EILS) (Tardy, 2004).

Secondly, English is the linguistic embodiment of the free market economy. Most economic transactions are carried out in English. The laws imposed by globalization force companies to be attentive to developments occurring outside their borders, as these borders mean little in the fiercely competitive market (Hasman, 2004). Outsourcing and offshoring have become frequent practices where corporations seek to combine cost efficiency and optimal productivity to earn greater and constant market shares. To allow the flow of such operations, the need for a common language emerged and English was the most convenient option (Phillipson, 1992; Crystal, 1997; Hasman, 2004).

Thirdly, the use of English is not exclusive to science and business, as most significant entertainment productions are chiefly performed in English. Paradoxically, with its raison d’être, entertainment becomes a serious matter when a heavy industry lies behind it. This industry not only generates huge profits and gains but also serves predetermined ideological agendas. It is this entertainment industry, whether in movies, video games, music, or fashion, that constitutes the most conspicuous and vibrant image of the power of the English language.

Indeed, the contributions to the development of human knowledge provided by English or through English need not be proven anymore. However, the impact of English does not stop at the limits of its factual contribution. Its hegemony outreaches the limits of its use, teaching, and learning. English conveys messages even to those who can barely recognize its words (Piller, 2001). The display of English suggests a manifestation of globalization, no matter how the latter is perceived. Frequently, English is associated with modernity, progress, and sophistication (Piller, 2003).

On the other hand, one may note that in some settings, English is seen as a threat to the local language and culture, as is the case in France (Phillipson, 1992; Crystal, 1997). Usually, this happens when there is a history of rivalry between the two languages or countries, and also when there is a shared colonial past. Even elsewhere, like in Nordic and Scandinavian countries, where these societies are deeply penetrated by English, they were compelled to promulgate laws such as the Swedish Language Act in 2009 to protect their language (Norrby, 2014).

Believing that English serves all equally well worldwide is a myth for many scholars (Phillipson, 2015). A number of these concedes that English was responsible for linguicide, that is the death of numerous minority languages, and was also a powerful agent for linguicism, generating linguistic discrimination against non-native speakers, preventing them from attaining some functions or overcoming some sociological hurdles (Phillipson and Skutnabb-Kangas, 1994;1997).

In light of the previous literature review and the discussion of the conflicting views about the impact of English, it is manifest that language teaching decisions should not be taken in isolation from the general context in which they are to operate. The role of language policy and planning is to unravel and evaluate the various elements of the surrounding environment and (re) direct them according to the needs analysis established at the onset of the policy’s conception. The present study was undertaken to bring some issues to the fore and try to launch a detached debate about the stakes engaged by the recent political decision for English teaching in Algeria.

2. Methodology

The present study attempts to assess how two aspects of globalization, economic and linguistic, interact and contribute to sociolinguistic change in Algeria. To this end, the study relies on the comparative analysis of advertisements for several products and services, using frequency distribution and percentage statistics. The analysis aims to demonstrate how many brands choose one or many languages to present their products in the market and assess the extent to which those languages contribute to attracting (new) consumers.

According to the official website of the Ministry of Commerce, labeling products in Modern Standard Arabic is mandatory. Furthermore, the law stipulates that one or more languages could optionally be added as long as they are understood by consumers. This second condition keeps the door open to the choice of any language and gives producers the right to decide by themselves about the most convenient option. The absence of specification about the optional language(s) provides bottom-up insights about the transformation of the linguistic landscape away from political decisions.

The corpus of this study consists of 20 brands representing 392 products and services. The products are exclusively convenience products whose characteristics are low price, ease of access, and frequent purchase. These characteristics correspond to a large market base, making the display and use of the products target a large number of Algerian consumers. This choice is also meant to reduce the impact of purchasing power and to widen the span of the consumer segment targeted by these brands, as most people have to use such products and hence are impacted or at least exposed to such labeling. In addition, when selecting the products, no distinction was made concerning the funding of the firms; that is, the products may come from public or private businesses. Even though the primary focus was on including samples from the most convenient products, their ensuing classification brought to the surface the role that could be played by the potential consumers’ age variable. Some products are unmistakably target adult women and men while others are predominantly directed at young people or children. Such features could be used as indicators to help identify the class of age to which the advertisement messages are sent.

The data were collected from the official websites of the sampled brands as they provide a comprehensive catalog of their products, their TV ads, and their local and international present or prospective market shares. Most convenience products available and in use in Algeria are included in the catalog. We can cite among these, grocery products, dairy products, beverages, sweets, laundry and cleaning products, and cosmetics. For cosmetics, most of the brands are imported from Europe or other parts of the world and are not included in this study. However, as the focus is on local brands only, the two most popular brands of cosmetics, Venus and Swalis, are part of the study sample. Furthermore, produce such as fruits and vegetables, fish, and meat are not represented as they are sold in Algeria by small businesses and do not hold a label.

Concerning the aspect of the advertisement being examined, it relates to the names of the products and the slogans of the producers. For instance, Bimo is a brand that has been on the Algerian market for over forty years. Initially, the number of products was quite limited, and they were presented in French only, as, for instance, Bimo Galette. But the number of products presently exceeds 25, and the languages used to advertise them vary too. It is this linguistic variety that constitutes the core of the present study. The focus is on the name and the slogan of a product and how they are presented to the final consumers because these two aspects are typically what consumers retain.

As the ads may be released through different channels, this study aims to explore the use of English through different media at the national level. TV and the internet are currently the most far-reaching mass media in Algeria and are thus the ones being examined.

3. Results and Discussion

The comparative analysis of the advertisements indicates that there is a variety of languages used in the labeling of the sampled products. Besides Arabic, French, and English, the use of Spanish and Italian was equally observed. For example, for pasta, Italian was often used to advertise Amor Ben Amor’s Cannelloni, or Spanish to sell products like Bifa’s Moreno, another Algerian brand. The results show that the channel through which the ad is released defines its linguistic orientation. To start with, television is considered to be the most accessible and popular mass media. Moreover, the Algerian audio-visual scene has been invigorated recently by the advent of a large number of private TV channels. However, these TV channels have to respect the framework stipulated by law and the directives of the Audio-Visual Regulatory Authority (ARAV). Within the latter’s attributions is the control of the form and content of TV programs, including publicity (ARAV official website). The two national languages, Arabic and Tamazight, have to be given the lion’s share on national TV channels. The examination of the different advertisements of the corpus under study shows that except for the names of the products, the content of the ads is almost exclusively in Arabic, where Modern Standard Arabic is mixed with Algerian/Dialectal Arabic (see Table 1 and Figure 1 below).

Table 1: Language options in brands’ websites and TV

|

Brands |

Language options in website |

Language options in TV |

||||||||||||

|

Grocery products |

Grocery |

Arabic |

French |

English |

Arabic |

French |

English |

|||||||

|

Cevital |

x |

X |

x |

|||||||||||

|

Amor ben Amor |

X |

X |

x |

|||||||||||

|

Extra |

X |

X |

x |

|||||||||||

|

Sim |

x |

X |

x |

|||||||||||

|

LaBelle |

X |

x |

||||||||||||

|

Soummam |

X |

x |

||||||||||||

|

Sweet |

Bimo |

x |

X |

X |

x |

|||||||||

|

Palmary |

x |

X |

X |

x |

||||||||||

|

Bifa |

X |

x |

||||||||||||

|

Boulba |

x |

X |

No TV ads |

|||||||||||

|

Beverage |

Hamoud boualem |

x |

x |

X |

x |

|||||||||

|

Rouiba |

x |

x |

||||||||||||

|

Ifri |

x |

x |

||||||||||||

|

Detergent |

Amir Clean |

x |

x |

|||||||||||

|

Aigle |

x |

x |

||||||||||||

|

Cosmetic products |

Venus |

x |

x |

Venus |

||||||||||

|

Swalis |

x |

x |

Swalis |

|||||||||||

|

Services |

ICT |

Mobilis |

X |

x |

x |

|||||||||

|

Djezzy |

X |

x |

x |

|||||||||||

|

Ooredoo |

X |

x |

x |

|||||||||||

|

Total |

09 |

47 % |

20 |

100 % |

05 |

26 % |

19 |

100 % |

0 |

0 % |

00 |

0 % |

||

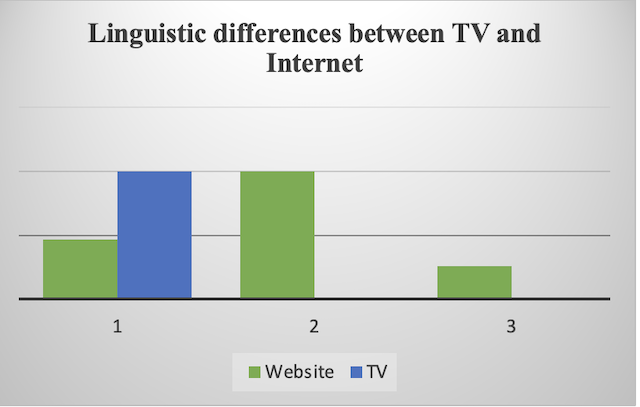

Figure 1: Linguistic differences between Internet and TV advertised products

1-Arabic, 2- French, 3- English

Figure 1 above shows how the screening of the products is done on the brands’ official websites as these provide the possibility of displaying different language options. The tendency differs tremendously from the one observed on TV channels (Table 1 above). All the brands’ websites propose an interface in French. Arabic is relegated to the second position with 47% in the linguistic choices of the websites. The official position of Arabic and the laws meant to promote it seems to have little impact on the internet. English comes as a linguistic option in only 26% of the websites. Bimo, for example, chose an official page on Facebook to publicize its products. Unlike a website, a Facebook page allows interaction. During the analysis of this page, it was impossible to miss the numerous interactions with the US Embassy in Algiers every time an original post in English, often a parody, was shared. This could be interpreted as a sign that English and what it represents seem closer to the average Algerian citizen. Among the other brands which have chosen English, and relying on the content on their websites, some are addressing international consumers as their products are available and sometimes produced outside the local market like Europe, Canada, or the USA (e.g., Hamoud Boualem, Cevital). The other option is that they seek to enter new markets (e.g., Palmary, Extra) so they have recourse to English to make their brand and products known. For these brands, the use of English results from a real need to establish communication and reach a wider audience, as Table 1 above indicates.

The beverage brand, Rouiba, as an example among many other Algerian products, advertises their products in Arabic only through TV, while on the official website, the content of this brand is exclusively written in French except for the slogan which appears in Arabic. This leads us to concede that the internet offers greater latitude to its users, either individuals or corporations. The brands that were surveyed (e.g., Bimo, Palmary, Rouiba) use the Internet to publicize their products without the constraints they have on TV, either related to duration, timing, content, or form. Most of these brands have their website or at least an official page on one of the social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, etc.).

Table 2: Brands’ selection of languages in slogans and products names

|

|

Products name |

Language for slogans |

||||||

|

Total used languages |

English |

English rank |

Total used languages |

English |

||||

|

Occurrences |

% |

|||||||

|

|

|

Cevital |

3 |

3 |

11.53 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

|

Amor Ben Amor |

2 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

2 |

1 |

||

|

Extra |

3 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

1 |

/ |

||

|

Sim |

2 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

1 |

/ |

||

|

LaBelle |

2 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

||

|

Soummam |

2 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

1 |

/ |

||

|

Sweets |

Bimo |

3 |

14 |

48.27 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Palmary |

2 |

15 |

68.18 |

1 |

1 |

/ |

||

|

Bifa |

4 |

16 |

32.65 |

1 |

1 |

/ |

||

|

Boulba |

2 |

07 |

58.33 |

1 |

/ |

/ |

||

|

Beverage |

Hamoud boualem |

3 |

01 |

16.66 |

3 |

1 |

/ |

|

|

Rouiba |

2 |

1 |

16.66 |

2 |

2 |

/ |

||

|

Ifri |

2 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

||||

|

Detergent products |

Amir Clean |

2 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

1 |

/ |

|

|

Aigle |

2 |

03 |

10.34 |

2 |

||||

|

Cosmetic products |

Venus |

2 |

27 |

55.10 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Swalis |

1 |

00 |

00 |

/ |

1 |

/ |

||

|

|

ICT Providerrrs |

Mobilis |

3 |

19 |

35.85 |

1 |

1 |

/ |

|

Djezzy |

3 |

05 |

26.31 |

2 |

1 |

/ |

||

|

Oreedoo |

3 |

06 |

23.07 |

2 |

1 |

/ |

||

|

TOTAL |

5 |

117 |

29.84 |

3 |

3 |

/ |

||

The analysis of the products’ names and their slogans provides another type of insight (see Table 2 above). The slogans are often presented in one language (mainly Arabic), but when some brands use two or three languages, English occupies a good position and is one of the options. The rate of the names chosen for the products in English is placed in the first position for 28.57% of the selected brands and occupies the second position with 21.43%. The cumulative result between the first and second positions gives us 50% of the total sample (see Table 2).

The classification of the different brands into categories highlights an interesting outcome. English is in the top position for 100% of the products which belong to sweets and snacks, 50% for the cosmetics category, and 33.33% for Information and Communication Technology (ICT) providers. It could be posited that these products usually target the younger strata of society which are still developing linguistically and culturally. This leads us to consider other category products such as groceries and dairy products, as well as detergents and other cleaning products traditionally taken care of by parents or older family members. The results show the latter items predominantly using French, confirming that they are addressing an older class of age which is linguistically settled and is still operating with the old linguistic norms. Services, on the other hand, are mainly related to mobile or internet offers with the three mobile operators Mobilis, Djezzy, and Ooredoo. In the case of mobile and internet services, young people are usually proficient users of ICT and their needs are more specific; however, older people do constitute potential users, hence the language choice seems rather balanced in this type of commodity.

All in all, these results show that there is little correlation between the presentation of the products on TV and the linguistic choices on the net. This shows that there is a divergence between bottom-up and top-down linguistic orientations, portrayed by the linguistic choices dictated by law and implemented in official mass media on the one hand, and the linguistic preferences of economic operators. On the other hand, English is not used to communicate substantial messages to consumers, as the level of linguistic complexity is below elementary. It is noteworthy to mention that some phonetic similarities between English and Arabic have been used for the sake of marketing strategies (e.g., “kool break” instead of “cool break,” “kool” which may be read in Arabic as “eat”). At the same time, the reluctance of official media such as TV channels to use English shows that the advertising political decisions are not really backed up at the sociolinguistic level.

The present study focuses on one aspect only of the linguistic landscape. The holistic interpretation of the results seems to imply that English is not used as a language but rather as an image to portray the values transmitted by this language. So far, the use of this language does not seem to play a semantic role by conveying meaning and thus does not deliver substantial messages. The selected brands’ producers are simply making use of the symbolic associations that their audience is prone to make whenever they come in visual contact with English. As Piller (2003) points out, English is used to suggest a monolithic form of modernity, progress, and sophistication not only to present the products or brands but also to attract their consumers. The Western and American way of life specifically is the one that is regarded by many consumers as ideal (Tsuda, 2008).

The growing presence of English in the streets of Algerian cities and towns (Nakla, 2020; Maraf and Osam, 2022) and in the marketing of different products is an instance that this language benefits from total tolerance, unlike the other used languages that might be resisted for historical, ideological, or political reasons, as is the case for French. Often believed to be the lingua franca of the world, English provides a general feeling of inoffensiveness that is pervasive in most environments. Policymakers and educators are no doubt aware that no language is ideology-free. Indeed, language policies go beyond the content of language textbooks, as languages are also used for symbolic reasons, with a direct impact on culture and identity. The use of English can promote a humane version of globalization if other (foreign) languages are not sacrificed for capitalist values. Tsuda (2008) introduced the Ecology of Language Paradigm to slow down the hegemony of English. He stressed that the maintenance of other languages is not only a human right but also an environmental issue. Therefore, the teaching of a variety of other foreign languages is likely to reduce occurrences of “linguicide” and hammer home respect for cultural diversity.

Conclusion

It seems axiomatic that the presence of English around the world both nurtures hopes and ignites tensions, making reactions swing between its prohibition and its endorsement. The position of Algeria is quite fortunate, as possibilities are still fully offered to place English in a position that would meet the Algerian user’s interests and needs. Currently, the form of English that is popular and spreading fast via the Internet and social media particularly, is more akin to Globish (Nerrière, 2006) or Global English than to English, relying mainly on the symbolism of English as a modern and fashionable language. Nerrière explains that Globish is useful, though it is a simplified version of a part of English intended to meet the basic needs in tourism and trade. In the same vein, Tychinin and Kamnev (2013) remark that simple sentences are perfect to express simple ideas, but complex ideas or descriptions in research require the mastery of complex grammar and a large vocabulary. The most valuable forms of English are thus the ones which will facilitate comprehension and production of knowledge. To attain this target, multidisciplinary actions are needed to design language policies that fit each nation’s needs and objectives.

As a final point, the language of globalization that is desirable and is worth promoting through official and non-official media should offer Algerian learners and educational institutions a smooth insertion into the economy, science, and knowledge in general. At the same time, Algerian policymakers should be wary of the stakes engendered by a massive promotion of English and should take into account the calls for caution made by renowned linguists who warn that attributing to English the power for integrating minorities, or for ensuring universal equal opportunities is pure fantasy (Tsuda, 2008; Phillipson, 2015). Such specialists agree that “Explicit language policies are needed that can ensure a balance between English and other languages” (Phillipson 2015). The present world is deemed to use English, but this should not imply the exclusion of other languages.