Introduction

The term MeToo was coined in 2006 by Tarana Burke, an activist and sexual survivors’ advocate from New York who aimed to create a sense of community to empower women. This initiative gained further momentum in 2017 when women started speaking out against the obstacles they faced to attain positions of power. The rise of the #MeToo movement marked a significant shift in how the media addressed women’s trauma surrounding sexual abuse.

Undoubtedly, the perception of rape as dismissible to the public eye is deeply rooted in patriarchal views that portray women as passive sexual objects. Donald Trump’s dismissal of sexual allegations made against his Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh1 illustrates how women are often forced to silently bear the responsibility for men’s actions. As a result, rape culture often perceives the act as a mere misunderstanding between two people rather than a serious crime. Tracey Nicholls argues, “A rape culture is one that normalizes and excuses rape, creating a social context in which the desires of privileged aggressors are prioritized over the comfort, safety, and dignity of marginalized populations seen as targets, as prey” (Dismantling Rape Culture 26). In essence, as society excuses and justifies toxic male behavior, the danger of rape culture lies in the failure to understand the politics of consent.

The #MeToo movement emerged at a time when feminist discourse focused on abusers and their defenders who believed that their assaults were simply misreadings of situations rather than criminal acts deserving punishment. Additionally, the protests and criticism sparked by the movement led to a wave of new media that offered a more in-depth exploration of gender exploitation, violence, and abuse, such as The Handmaid’s Tale (2017), I May Destroy You (2020), and The Morning Show (2019). As my article will argue, exploring these shows as well as comics will allow me to highlight how patriarchal culture turns a blind eye to small mistreatments, leading to the weaponization of consent and the oppression of women into silence.

1. Jessica Jones : Navigating the Alias Divide

The character of Jessica was first introduced as the alter ego of the superhero Jewel in the first R-rated graphic novel Alias, created by writer Brian Michael Bendis and artist Michael Gaydos, which ran from 2001 to 2004. The protagonist is a failed costume vigilante turned private investigator who now uses her superstrength and ability to jump high to solve superhuman cases. From the get-go, the comic presents her as a heavy drinker and smoker with a very bad temper. She lives and works alone, but she is still always seeking male validation. The last arc of her comic run, Alias: The Secret Origin of Jessica Jones, sheds light on Jessica’s backstory.

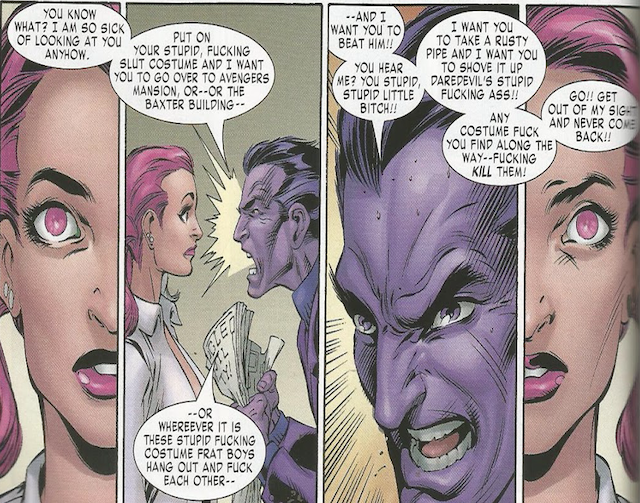

Fig. Brian Michael Bendis, Alias vol. 4, p13, 2004.

Jessica is revealed to have a past as a costumed vigilante named Jewel before she was abducted by the mind-controlling villain Kilgrave (Purple Man). Using his power of persuasion, he enslaved her for eight months during which she was forced to sleep on the floor, lie at his feet, and bathe him (Bendis 13), as well as steal, mutilate, and destroy at his command, ordering her to “beat” his enemies (Bendis 17). However, after being sent to kill Daredevil2, she mistakes the Scarlet Witch for him and attacks her instead. This leads to her finally mentally freeing herself with the help of Jean Grey—a fellow superheroine—only to be beaten up by the male Avengers superheroes who do not recognize her.

While, arguably, this arc follows the pattern of previous comic narratives in which the woman is injured, abused, and disempowered, I would highlight that Alias still attempts a subversion to the narrative. Anna F. Peppard underlines in her article, “I Just Want To Feel Something Different,” how the narrative, “[emphasizes] Jessica’s complex subjectivity as well as [implicates] male superheroes and superhero comics’ sexist conventions in her multifaceted abuse” (Peppard 158). Indeed, through this arc, the creators demonstrate how Jessica’s abuse was perpetuated not only by the villain but also by the male superheroes. This highlights how even the superheroes benefit from patriarchal violence as they feel justified in their assault.

Yet, despite this commentary on gendered abuse, the character’s last arc ends not with Jessica healing from her trauma but rather by her declaring her love to her partner Luke Cage and deciding to raise a child with him which fails the character as motherhood becomes the solution to her abuse. That is why it is important to note how Rosenberg decided to explore this storyline in the first season of Jessica Jones without using the themes of motherhood. The series chooses instead to heavily lean on its “grittier socio-political edge” (Green 174). It seems that with the change in medium, the show prefers to focus more on exploring the impact of sexism and rape culture on the characters as well as re-evaluating the abuses enacted upon them. While the comic book showcases Kilgrave’s power through acts of sexual humiliation, Rosenberg chooses to demonstrate his powers not through such explicit acts, but rather by a continuous battle over Jessica’s agency as he repeatedly commands her to “smile” for him. Thus, by choosing to avoid such graphic displays of gratuitous sexual violence, Rosenberg, it can be argued, displays a more vicious form of aggression.

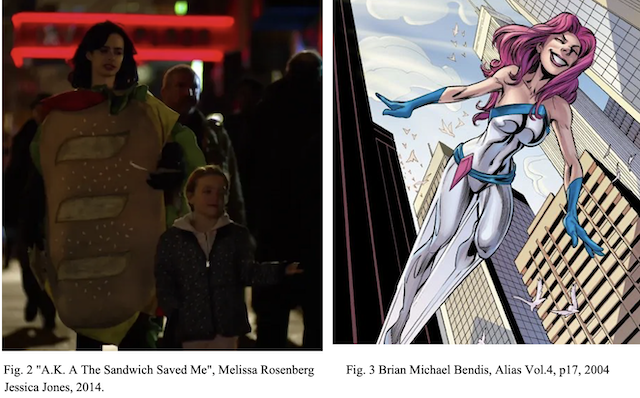

Another aspect that was altered in the show is Jessica’s costume. Indeed, even though Alias introduces Jessica as a character that hung up her costumed vigilante days behind and only wears normal attire, she still had a long period of wearing a tight conventional “silver and blue costume” where her figure is on display (Green 177). On the other hand, the show rejects this idea during the fifth episode of the show, “A.K.A the Sandwich Saved Me,” in which Trish – Jessica’s best friend – tries to convince her to wear a similar costume. Not only does Jessica reject the outfit, but she also scoffs at the idea by saying that, “the only place anyone is wearing that is trick or treating” (“A.K.A The Sandwich Saved Me” 23 :30-23 :32). In other words, the show seems to distance itself from the comics and their interpretation of a superheroine. Later in the same episode, Jessica saves a person while wearing a sandwich costume. Furthermore, the comic showcases Jessica being forced to use her femininity to get what she wants, “[She] has to put on makeup and a skimpy dress, and then she has to submit to an inspection […] the comic devotes most of a page to depicting her in the getup in a sultry pose” (Green 136)3. In contrast, Rosenberg asserts her lack of desire to see Jessica in, “high heels and a miniskirt using her feminine wiles to get information out of a suspect.” (Hannah Shaw-Williams)

Thus, even though Gaydos and Bendis’s work attempts to foreground a departure from previous female superheroes representation they still fall victim to the same conventions. Furthermore, even if the comic tries to explore female trauma and highlight surviving assault, it still does not explicitly explore the abuse shown by Kilgrave nor does it consider it as rape. The character in the comic repeatedly denies being sexually assaulted as she doesn’t consider Kilgrave’s treatment of her or other women he put under his command as rape. By refusing to acknowledge Kilgrave’s treatment as such, Bendis proves how patriarchal society dismisses rape so easily.

2. Exploring the World of Jessica Jones: Kilgrave, A.K.A. a #MeToo Movement Representation

As I mentioned before, Rosenberg chose not to show explicit scenes of rape on screen but rather to explore its damages. While the show aired before the start of the #MeToo movement, it is still worth noting how much attention the hashtag garnered around the violence and the abuse women must endure. These discussions led to the show being retroactively read as an important #MeToo text since it resonated with rape culture and power imbalances.

Indeed, the show used the popularity of the superhero genre to discuss the complexity of surviving assault. Rosenberg notes in an interview given to the Los Angeles Times that, “With rape, we all know what that looks like […] We’ve seen plenty of it on television […] I wanted to convey the damage that it does. I wanted the audience to really viscerally feel the scars that it leaves.” (Hill). Thus, while both texts attempt to illustrate how Kilgrave exploits Jessica and humiliates her to assert dominance, I would argue that the comic uses the abuse as titillation ; the show, in contrast, openly tackles the matter. For instance, during the eighth episode of the first season, Jessica confronts Kilgrave in the following dialogue :

Kilgrave : We used to do a lot more than just touch hands. Jessica : Yeah, it’s called rape. Kilgrave : What ? Which part of staying in five-star hotels, eating in all the best places, and doing whatever the hell you wanted, is rape ? Jessica : The part where I didn’t want to do any of it ! Not only did you physically rape me, but you violated every cell in my body and every thought in my head. Kilgrave : That is not what I was trying to do. Jessica : It doesn’t matter what you were trying to do. You raped me. Again, and again, and again. Kilgrave : No. (“WWJD”, 00 :28 :48 – 00 :29 :19)

This exchange perfectly highlights the unaccountability of rape culture. Kilgrave not only rejects Jessica’s claim but is confused by it. Similarly, during the #MeToo movement, many accused individuals claimed in their apologies to have misunderstood where and when to stop4. As Pasco and Hollander define in their work, “Good Guys Don’t Rape,” “[Rape culture] includes not only engaging in activities legally defined as rape but also engaging in other forms of sexual assault and non-consensual sexual interaction […] blaming sexual assault survivors for their victimization” (69–71). In other words, the idea of rape culture is that society upholds shared behaviors regarding gender performance. It is, then, understood that rape in a patriarchal culture reinforces shared cultural views around gender and sexuality.

In other words, the institution of rape will not only defend the man who committed the assault but will also reinforce the oppression of women if he strongly believes that rape did not occur. In fact, Mathew Thompson notes in his work, “Challenging Typical Ideas of Heroism and Toxic Masculinity in Alias and Jessica Jones”, “While the first series of Jessica Jones came out before the #MeToo movement began in earnest, it emulated ideas shared by institutions that were unwilling or even outright refusing to listen to the claims of victims” (156). This idea is reflected in the show by Jerri Hogarth, Hope’s lawyer, who not only denies Kilgrave’s rape but also denies the possibility of it, as she says, “if there really was a man who could influence people like that, I would hire him to do all my jury selection.” (“A.K.A Crush Syndrome” 10 :53-10 :56). This emphasizes the idea that rape is not only rare but that false accusations of it are more common.

The #MeToo movement underlined how the idea of victimhood is weaponized by aggressors as well as their misunderstanding of consent. Banet-Weiser defines this idea in her article, “Ruined Lives”, as “Powerful and (almost always) white men in positions of privilege took up the mantle of victimhood as their own in earnest, often claiming to be victims of false accusations of sexual harassment and assault by women” (61). So, Rosenberg’s choice of making Kilgrave a white Englishman instead of the purple man depicted in the comics offers a perfect representation of the movement’s main criticism. As such, by having the culture around gendered abuse influence the director, Kilgrave becomes an embodiment of patriarchal oppression that works to suppress female identity and subjecthood.

This is further proved by Kilgrave’s lack of desire to control the world ; he prefers to control women instead. His commands and abuse as a result become, “an act that is at once sexual, violent, gendered, and political, and that attacks not only a woman’s body but also her claim to subjecthood” (Banet-Weiser 164). By forcing Jessica to smile, to wear dresses, and perform femininity according to Kilgrave’s own interpretations of gender, she is objectified and forced to appeal to his idea of femininity. While he is drawn by her power, he still seeks to own and control it for his interests. As Lili Loofbourow notes in her article for The Guardian, “Kilgrave’s obsession with smiling is a pointed comment on the widespread phenomenon of men hectoring women to smile on the street” (Loofbourow). In fact, this objectification is proven by the fact that during their first meeting, after seeing her exploits, Kilgrave starts describing her physical features as he calls her a “vision” despite her lack of “sense of fashion” (“A.K.A The Sandwich Saved Me” 37 :24-37 :30) then commands her to follow him for dinner. These interactions showcase how Jessica’s body becomes Kilgrave’s ultimate symbol of control as he turns her, literally, into a passive object that enacts his every fantasy.

Lastly, the comic attempts to tackle an idea of sisterhood through Jessica and Carol Danvers’ friendship. Yet, Jessica is depicted as jealous and erratic ; her friendship with Carol is depicted on a very surface level and never detailed further beyond talks of boys (Johnson 138). This, arguably, goes against the idea of sisterhood as understood in Rodak’s article “Sisterhood and The Fourth Wave of Feminism” as their bond is based solely on defeating male oppression resulting in a sisterhood that becomes, “based on resentment … as it creates relationships understood as a type of alliances between women to confront the male oppression. Such an approach … represents a very narrow concept of sisterhood, if any.” (Rodak 131S). By contrast, in the show, Jones’s driving narrative is her desire to free Hope and protect Trish. As a matter of fact, throughout the season Jessica works closely with Trish to free Kilgrave’s victim Hope Shlottman.

Additionally, Jessica’s interaction with her best friend, Trish, and Kilgrave’s latest victim, Hope, brings to mind Rodak’s description of sisterhood. She notes, “The two main characteristics of sisterhood […] are the following : i) a concern with identity […] ii) An emphasis on solidarity, declined into […] supporting each other.” (Rodak 5). These characteristics are not only displayed throughout the first season but they are solidified by the last episode as Jessica chooses to save Hope instead of running away. For instance, her bond with Hope goes beyond facing male oppression as she feels a kin desire to liberate her from his control and push her towards finding her agency. Furthermore, her last words before defeating Kilgrave are a declaration of love directed to Trish (“A.K.A Smile” 41 :51-41 :53), this heightens the sisterly bond between the two friends and emphasizes their solidarity with one another. Furthermore, Trish’s support is shown repeatedly as she becomes the person who pushes Jessica to use her powers, to rescue Hope, aid Kilgrave’s victims and finally face him. As Steiner notes in her article “Jessica Jones and its Legacy of Female Anger”, “All of the women in Jessica Jones are in pain, but they refuse to be passive. They cry, they rage, they self-destruct, but they are always active, […] they can only save themselves and each other.” (Steiner). Thus, these moments emphasize the collective identity that Rodak describes and are what leads to Kilgrave’s downfall.

Conclusion

All in all, while the comic creators, on the one hand, attempted to subvert norms, their characterization of gendered abuse highlighted how dismissive acts of rape become in a society that upholds patriarchal views. Their characterization of Jessica Jones offers a good attempt at showcasing the objectification superheroines underwent in the superhero genre. The show, on the other hand, managed to offer a more in-depth characterization of gendered abuse not only through its exploration of trauma after rape but through its examination of how gendered performativity sustains rape culture. Moreover, although the show came out before the #MeToo movement, I would argue that it offers an understanding of the movement’s key aspects as it must be read as a backdrop to the show’s exploration of the complexities of sisterhood, trauma, and recovery.