Introduction

Drawing is a method of communication that humanity has developed since its first desire to narrate stories about life and existence. Humans used images for the transmission of ideas, and feelings, and for sharing their vision of reality. Alongside painting, sculpture, and pottery, giving shape to ideas has always been an effective means of expressing them. As time passed, these forms of expression became part of what is now known as “artistic expressions,” embodying the identity of specific cultures. Among these artistic expressions, we can include a phenomenon that came into its fullness in 1939 in the United States: the comic book.

During the 20th century, the United States positioned itself as the greatest power not only economically and politically but also culturally. Undoubtedly, American culture highly influences our sense of reality, whether through music, cinema, or literature. Despite its limited penetration compared to earlier mediums, the comic book is no exception. Initially considered mere entertainment for teenagers, it has been able to position itself as a serious and educational art form, no less important than other literary genres. One of the most significant contributions that comic books have made to popular culture is the creation of the superhero myth. Indeed, superheroes, as they are constructed, offer a window to a world where power balances, competing ideologies, and power conflicts are depicted through allegories and metaphors. Like any other artistic expression, the produced art is not created in a vacuum; it responds to the fears, aspirations, desires, and hopes of its society and the historical context in which it appears and develops.

This article suggests a social constructivist reading of the comic book Captain America: The New Deal, which appeared in 2002. The comic book is presented in six episodes, all completing the storyline of a captain declaring “war on terror.”1 It was published by Marvel Comics, one of the most important leaders in the comic industry in the United States.

After the 9/11 attacks, Marvel Comics used the character of Captain America to send a message of hope and unity to its readers. The importance of the event cannot be denied; it is perceived as a modern event that has significantly affected American domestic and international policy. American policy entered a new phase of expansion with a solid argument: the war on terror. It then announced a war against the abstract concept of terrorism.

Captain America: The New Deal creatively reflects the reality of the United States after the event. To demonstrate the importance of cultural products in constructing social realities, the analysis of “Captain America: The New Deal” enables us to show that art, as a response to 9/11, is part of the natural power that influences social imagination. Additionally, it contributes to the construction of a social reality by supporting the social hegemony that empowers the American government. This work offers an understanding of the propagandistic American discourse used to fuel feelings of patriotism and construct the concept of terrorism in the American imagination.

1. Social Constructivism and Terrorism

To conduct this research, social constructivism has been selected as a tool to demonstrate how the concept of terrorism has been socially constructed in order to empower the social doctrine of the United States post-9/11 attacks. “In particular, post 9/11 and with the rise of Critical Terrorism Studies, a discourse-centered terrorism studies have emerged. Here terrorism is not understood as a physical fact but as a social construction” (Jackson, Smyth, and Gunning 2007:2). Terrorism gained more attention in academia after the attacks. Nonetheless, its abstract nature made it difficult to give it a definition and explain it by critical theories.

Social constructivism advocates the idea that the construction of reality within a society is a two-way process; people are constructed by and construct their societies. Besides, it puts into question the legibility of reality by proving that the knowledge acquired is not true but becomes true through social agreements or a “social contract”2, which represents a set of rules that people are supposed to follow. In addition, fundamental to constructivism is the proposition that human beings are social beings, and we would not be humans but for our social relations. In other words, “social relations make our construct people – ourselves – into the kind of being that we are” (Onuf, Kubalkova, and Kowert 2009 :59). It means that knowledge arises out of human relationships and interactions; what we know has been constructed within a cultural and historical context.

Furthermore, human interactions are mainly shaped by language. Language is part of culture, and thus, it unifies people within a linguistic community. “The primary function of language is communication rather than representation, so language is a social phenomenon” (Chen 2015 :88). Within a society, people share a common culture, and language is part of this culture. A specific use of words and metaphors becomes part of it and is only understood by people within that culture. This linguistic meaning is transmitted by social agents and becomes part of their sociolect. The significance of the American dream, for instance, would be understood entirely differently by non-Americans. The American Dream revolves around the idea that the United States is a land of opportunities for people. For an American, it is part of their national identity. Thus, interpretation of a word is linked to a person’s cultural background and their social experiences. Therefore, “linguistic meaning consists in the correlation of language to the world established by the collective intentions of a language community” (Chen 2015:88). People develop knowledge about the world via social interactions, resulting in a linguistic meaning shared by a linguistic community; hence, social reality is socially constructed through people’s manipulation of language, and this reality will be transmitted from one generation to another until becoming deeply ingrained in society and becoming “common sense”3

Another important element in the construction of language is social hegemony. Knowledge construction is politically driven because, in a hegemonic state, “the superstructure”4 is controlled by the elite, and thus, they control the information circulated in different institutions: schools, churches, mosques, and even the media.

The distribution of power in society certainly has effects on the meaning-conferring and the popular degree of linguistic expressions, since it is much easier to popularize words, utterances, meanings, and even speech styles used by political leaders and other public figures than to popularize those used by ordinary people. The conveyed linguistic meaning becomes doctrinally oriented, accepted by the linguistic community, and becomes fixed and unchangeable (Chen 2015 :96).

Terrorism has been selected in this work as an example of a socially constructed term in American society. Richard Onuf, one of the proponents of social constructivism, suggests that terrorism is constituted through discourse; in other words, we all make terrorism what we say it is (Onuf 2009:54). After 9/11, terrorism needed an American definition for the American people, and since terrorism is constituted through discourse, political discourse, the institution gave it a sociolinguistic meaning. Indeed, “politics, in particular counter-terrorism policy, are one among many linguistic devices which play a role in the discursive construction of reality” (Spencer 2012:7). The political institution makes assumptions about people’s reactions and selects the appropriate policy to generate the required popular reactions.

People, in moments of disillusionment or when affected by phenomena, natural or social, that they do not or cannot see, respond as agents by putting what has happened to them in an institutional context (Onuf, Kubalkova, and Kowert 2009:62). When people of a nation live under the same fear, in this case, the fear from terrorism, they look for protection and gather around their nation or the government.

Accordingly, the words of the government were not doubted or criticized; there was a strong unity and unwavering patriotism. Terrorism was defined by George W. Bush as “terror”. Since language is an important element in the social construction of reality, terrorism for Americans became terror exercised by the enemies of peace, democracy, and the free world. It also signified terror guided by religious fanatics; Al Qaeda5 Undoubtedly, this does not doubt the existence of the violent act itself but the interpretation of the actions and their long-lasting meaning.

2. The 9/11 Attacks and Heroism

September 11th, 2001, was an important day in American history. Two planes were hijacked by a group of terrorists and targeted the Twin Towers in Manhattan.

The event was traumatic for Americans. “The truth that showed itself at the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon for the time being unspeakable because, unlike other countries, this truth had yet to be conveyed to the Americans” (Hyde 2005:5). Up to that date, Americans had heard about acts of violence in other countries; however, the threat had always seemed far away from their safe place. It was shocking because Americans knew that the United States was the most powerful nation in the world, and it was inconceivable for them that an attack could be directed towards it.

The general sentiment in America was defined by feelings of sadness, anger, and fear. It was the right time for political influencers to make sense of the chaos and participate in healing a terrorized population. Besides, an anxious public could be easily misled and was more likely to act in favor of its government than against it. It was the right moment to show their patriotism. What was important about the event is that the government received little criticism because the event ‘prompt[ed] senses of unity against the foreign enemy and accept[ed] personal sacrifice for the sake of protecting American ideologies of freedom’ (Garcia 2016:4). The American values of freedom and democracy were used and advocated to keep the people united by both the government and the media. Indeed, “Popular geopolitics, or the construction of scripts that mold common perceptions of political events” (Dittmer 2013 A: 1). After the attacks, there was a political anti-terrorist discourse aiming at influencing individual and collective understanding and orienting public opinion in a pro-governmental direction.

It is the articulation of 9/11 that the Bush Administration used to make security a goal for the American people. “Americans had to live with the new mantras, with us or against us. They had to live under the cloud of daily reports of color-coded terror alerts telling them how likely another attack would be, forcing them to live with the fear of reliving 9/11 each day” (McGuire 2014:12–13).

Moreover, there was high media coverage of the events. The media succeeded impeccably in showing the terror, sadness, and fear left by the attacks, and they were also able to create a highly patriotic reaction. “Just because we can identify rulers, we should not conclude that they alone do the ruling” (Onuf, Kubalkova, and Kowert 2009:75). What is meant by this quote is that the government alone would not have been able to reach its goals without the help of other institutions, for example, the media. Television and the press relied on photography to create the required emotional impact on people. By showing photographs of all the victims and putting a small biography under each one of them, they made the victims closer to people. It was a way to create a personal link between the victims and the audience and make the attacks more relatable. Photographs are endowed with a powerful silence in engraving the attacks in individual memory; “they speak no words, use no rhetoric, flourish no linguistic embellishment or evasions; they freeze transient motion into lasting stillness” (Kroes 2009:71). Besides, the media were also able to create a strong feeling of patriotism by showing the heroism of police officers and firemen in helping people in Ground Zero. This was ‘mere opportunism in seizing a cultural moment. Rather manipulators of the image of firefighters as heroes tapped into a deeply entrenched and long-standing American popular culture script that defines the most compelling forms of heroic action […] to advocate for war’ (Connor 2009:93). The notion of heroism is part of American popular culture and has been used by the media and in comic books to endorse the political discourse of 9/11.

3. Captain America: The New Deal (2002) and Nationhood

One way in which linguistic meaning is associated with culture is through the consumption of popular culture. Jason Dittmer suggests that “producers of comic books view their work as more than just lowbrow entertainment; they view their works as opportunities to educate and socialize” (Dittmer 2005 B: 672). Accordingly, one of the aims of the writer is to influence the reader’s understanding, construct a social reality for him, and thus, influence his attitude.

Within American popular culture, there is a sociolect constructed by and for the American people. For instance, after the attacks, George W. Bush did not have to explain what nationhood and patriotism were because they were already ingrained in American culture. He knew that his people already had the social background that would enable them to understand his speeches and the messages he wanted to convey. Societies have a popular discourse that makes particular diction easily understood by its members. Popular culture, whether music, graffiti, street dance, or comic books, plays a part in the creation of a collective identity. The main contribution of comic books to popular culture is the introduction of the concept of superheroes. These characters represent greatness, generosity, and altruism.

Captain America, the comic book character, embodies the American Dream. He was first introduced in 1941, before the American involvement in World War II, at a time when American patriotism was at its peak. “Captain America’s narrative of origin is a 1941 nativist fantasy of individualist patriotism, with Captain America and, by extension, American values contrasted against his un-American enemy” (Dittmer 2005 B: 631). Captain America: The New Deal (2002) was not the first time Captain America was used as a pro-American symbol. He is not only a traveling propaganda emblem but also a symbol of America as a peace-loving nation in the face of barbarism. The comic book has always taken a political stance, specifically, a pro-American one. This was evident, for instance, in the comic book before Pearl Harbor, where the cover depicted the captain punching Hitler, demonstrating America’s alignment with the Allies and its anti-Nazi sentiment. Captain America has always played a role in constructing political reality and emphasizing the importance of the United States in promoting democracy worldwide.

After 9/11, the situation was no different. In fact, “the events paralleled the bombing of Pearl Harbor in many ways, including garnering nationalist responses against the offenders, triggering a unity sense of patriotism and dedication to the country” (Garcia 2014:11). Similarly, the government called for unity and support.

3.1 Captain America: The New Deal

The New Deal itself is already part of the American sociolect and history, referring to an era of change and ambitious decisions. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt made social reforms to overcome the economic crisis of 1929. Readers of the comic book are likely to make the connection between the New Deal and the new challenge the United States faced during the attacks.

Captain America, or Steve Rogers, is the main character of the book. He is the quintessential white American, with blond hair and blue eyes. Stan Lee, comic book writer and former writer of Captain America, says that the captain represents the best aspects of America: courage and honesty (Stan Lee qtd in Dittmer 2005 B: 629). He is undoubtedly the embodiment of the American Dream. What is peculiar about Captain America is that he is just a skilled athlete who wields a shield as his only equipment, emphasizing the symbolism of protection from aggression. Therefore, since the captain personifies the United States, he is rightfully portrayed as protecting himself from aggression. The impact that the captain has on readers is significant because of his “ability to both embody and narrate America, a feat that symbols like the bald eagle or the flag cannot accomplish” (Dittmer 2005 B: 630). He contributes to the social construction of the United States’ defensive rather than offensive image.

The book should be analyzed in the context of its raison d’être, as 9/11 shapes the entire story. Writing the narrative and storyline permitted the construction of reality and gave meaning to the chaos left by the attacks, providing a shape and a name to the enemy, which is terrorism. The captain has the “ability to connect the political projects of American nationalism, internal order, and foreign policy with the scale of the individual” (Dittmer 2005 B: 627). Another important aspect of the comic book is its target audience, usually a young audience with little interest in politics and little understanding of the complexities of geopolitics. As a result, the construction of political awareness and social reality will be shaped by the content conveyed in the comic books. In the context of 9/11, Captain America: The New Deal participated in framing terrorism and influenced readers to adopt a pro-American stance in the fight against “terror” in Iraq and Afghanistan. Since the captain embodies American values and policies, he promotes the United States and its overall policies.

3.2 American Nationhood

Following 9/11, and amidst the high patriotic reactions, the notion of nationhood strengthened the public’s connection with the government. They both wanted the best for the nation, for America. This sense of belonging and the incorporation of real settings in the book were among the techniques used by the writers to foster nationalism and create an emotional connection with the fictional work.

The call for patriotism in the work was not only demonstrated through the words of Captain America but also the depiction of different American landscapes. The importance of incorporating real landscapes in the comic book is evident in the creation of a direct link between the reader, the book, and reality. Centerville, in the book, which signifies the center of the city, is a fictional representation of New York, expertly illustrated by the artwork of John Cassady. American readers would easily recognize the streets and the town. Similarly, the Twin Towers in the comic book are a direct allusion to the setting of Manhattan. The use of real settings helps strengthen cultural bonds. The World Trade Center and all the illustrations of New York exist in the imagination of the readers and are part of their identity.

American television dubbed “Ground Zero” as a “sacred place”. The sanctity of the site of the attacks cannot be violated. Furthermore, it became evident that everything said and done by the government and the media was for the sake of the nation. The feelings of pride, anger, and the desire for revenge were all key emotional factors for the American people. The term Ground Zero did not emerge out of nowhere at that time; it was already familiar to Americans. The term “emerged quasi-spontaneously as a proper name in the American mass media immediately after the attacks. As a proper name, uncontextualized and capitalized, it refers to the site formerly occupied by the World Trade Center towers; as a more general idiom, it refers to the impact of a bomb” (Redfield 2007:62). Hence, the term was already part of the American sociolect since it was first used to describe the bomb impact in Hiroshima and Nagasaki6

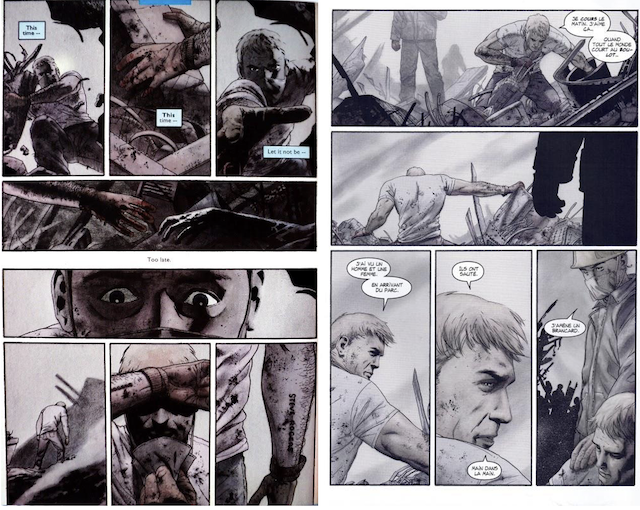

From the opening pages, Captain America: The New Deal portrays a somber image of “Ground Zero”. John Cassady chose a bleak panorama to convey the sadness, hopelessness, and chaos in New York at that time. The captain appears terrorized by the attacks. The absence of colorful images and the use of black, white, and gray symbolize the sadness of America, the loss of the victims, and the dust in the city.

Source: The New Deal, John Ney Reiber and John Cassady, 2002, 5–6.

Observing these images, the reader would immediately recognize the sacred place. He would also feel a connection with the terrorized character. Therefore, the setting plays an important role in making the reader realize that it is a fictional reality.

4. The United States and the “Other”

When President George W. Bush declared that one could either be with the United States or against it, he made the American individual involved by a moral duty towards his nation. Therefore, opposition to whatever the government decides is considered an act of betrayal. Additionally, the use of the expression “with us or against us” creates different dichotomies to define the enemy and to place him in the position of the “other”.

The concept of Otherness is very significant in this regard since it participates in the fabrication and construction of the enemy. The 9/11 attacks demonstrated that the enemy was an Arab Muslim man who belonged to a terrorist organization called Al Qaeda. The official discourse accused Osama Bin Laden of Terrorism against the United States. Accordingly, the position of the American government participated in the social construction of terrorism in the American mind. It was an attempt to “re-establish the definite binary of us-versus-them […] thus re-establishing the US sense of self-righteousness” (Garcia 2014:11). As mentioned before, there was a set of dichotomies that gave shape, a name, a religion, and an identity to terrorism. There was a clear distinction between good and evil, between religion and Islamic fanaticism, and between democracy and religious dictatorship.

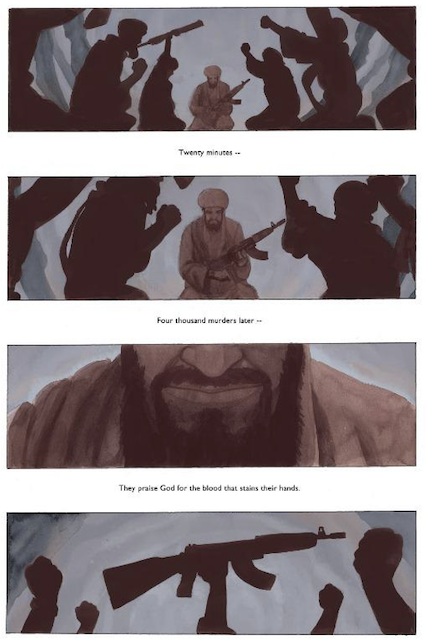

In addition to the real American heroes presented in the American media, the firefighters and policemen were not the only heroes. The fictional superheroes such as Captain America were equally utilized. The hero is determined to protect the United States from the Muslim terrorist group attacking Centerville. The story presents a man who holds a knife in the aisle of a jetliner, surrounded by terrorized passengers. Besides, the book shows images of a group of men with long robes and long beards, likely to be Middle Eastern, gathered around a radio station waiting for confirmation that the terrorist attacks were successful. The men, after hearing the news, grab their assault rifles and start celebrating. This is to say that the book offers an allegorical scene of the passengers on the real jetliners and the reaction of the terrorist group as it is assumed to have happened during 9/11.

Source: The New Deal, John Ney Reiber and John Cassady, 2002, 2.

It should be maintained that no direct or explicit allegation was made against Arab Muslims. However, the presented images and the allegories used by the authors reaffirm the official social construction of terrorism, and emphasize the otherness of the Arab enemy. The key evidence in this is the portrayal of Faysal Al Tariq, the leader of the terrorist group in the book, as an Arab terrorist.

The book agrees with the official social construction of terrorism, with the association of terrorism with religion. The captain referring to the terrorists says, “They praise God for the blood that strains their hands” (Cassaday and Rieber 2002:7). This passage demonstrates a direct link between terrorism and religious drives. Besides, the religious fanaticism is shown when Captain America threatens a terrorist, and the latter answers “Death is peace for me” (Cassaday and Rieber 2002:13). It shows that these terrorists are not afraid of death because they are doing this for their God, it is a religious sacrifice.

The attacks in the comic book occur seven months after 9/11 which highlights the continuation of the threat on America. As a result, if terrorism is not stopped, is not fought, this is what would happen to the United States. War is demonstrated not as an option, it is not something chosen, it happens when you are attacked and when you must defend your nation. The war between Captain America and the terrorists is a war between good and evil.

The victory of Captain America at the end of the story shows the inevitability of violence to stop terror, the book gives a justification for the violence committed by the American government in the Middle East to stop terrorism.

When Captain America says in the last page “I killed Faysal Al Tariq, the responsibility the failure is mine” (Cassaday and Rieber), the reader feels the captain’s regret for taking a human life but he also understands that there is no other solution to stop terrorists but fight them, hence, this is a fictional reflection of what the Bush Administration did in Iraq and Afghanistan. Equally important, this “does not mean that such a constructivist perspective denies the real existence of terrorism, but what these people and their deeds mean is a matter of interpretation.” (Spencer 2012:2). The social background, the political discourse, the linguistic meaning conveyed by the language of a specific community, all participate in the construction of meaning and thus in the construction of reality.

Conclusion

The evolution of American ideological discourse within comic book storylines has been notable over decades. The content of comic books is therefore considered both a representation of reality and a response to specific historical moments. The creation of superheroic figures gained popularity and acceptance among the American audience, becoming a part of American popular culture. This underscores the importance of studying these artistic manifestations which portray a reality based on ideology and its social construction.

Captain America has always been a fictional character through which the political, social, and economic aspects of our world are projected as a reflection of social reality. The character of Steve Rogers has been one of the key creations in the world of adventure. Born during the Second World War as an anti-fascist fictional expression and as a representation of freedom and democracy in the face of oppressive regimes, he has always shown his devotion to protecting his nation from external threats, as he perfectly did in “Captain America: The New Deal” to protect America from terrorism.

Social constructivism, as a theory, participated in demonstrating the implications of Captain America in following a propagandistic logic to influence the social ideology of the United States after the attacks. The social construction of terrorism after the attacks contributed to the profiling of terrorism, making its conception easier for readers.

The propagandistic role of Captain America adapted to the socio-historical context of that time and demonstrated the artwork’s ability to play a political role. Firstly, by adhering to an official script and secondly, by portraying real American settings. The connections between the work and real life became only natural.

Captain America is an artifact that embodies American values and perpetuates its hegemonic position. The work succeeded in legitimizing American policies domestically and internationally. The character of Steve Rogers calls for patriotism and love of the nation. Undoubtedly, the work displays a degree of subjectivity since the character presents himself as a guardian of American values, an emblem of American ideals. After 9/11, Captain America acted as an ideological channel through which the terrorist evil was shown and constructed. The captain participated in defining terrorism as an opposing entity to America, to freedom. The work aids in the social construction of terrorism by providing sufficient elements for readers to link reality with fiction. The captain reinforced the American heroic identity, fulfilling his role in naturalizing the idea of going to war and defending the American position as a world liberator. The work served as a means through which the fears, concerns, and hopes of the American population were expressed, and certainties about terrorism were revealed.