Dedication to the illustrious dead shadows, arise, and read your fall ! Behold the history of the. Last man. (Shelley, The Last Man, 407).

“He who was living is now dead

We who were living are now dying” (T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land, 328-329).

“Here was a new generation dedicated more than the last to the fear of poverty and the worship of success ; grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken…” (215-216)

Introduction

These are the words of the American author Francis Scott Fitzgerald describing Americans during the 1920s as the Lost Generation in his novel “This Side of Paradise.” Frederick Nietzsche then gives this sense of “loss” a global and philosophical dimension, explaining that the Western world is living in a state of “mythlessness.” According to the author, the lack of myth and mythic beliefs puts humanity in a state of illusion1. Hence, modern artistic productions respond to these states of delusion and alienation in an attempt to transform history and shake consciousness. Relying on theories of adaptation and a Barthesian perspective on myth and connotation, the focus of this article is to look at the adaptation of the dystopian novel through twenty-first-century apocalyptic films as a reaction or response to the disillusionment of Man and modern life. These films look at and question humanity and the sense of despair, emptiness, and lack of purpose that has been spreading and invading the human mind since the end of WWII. The artistic response consists of creating new myths reviving the mythological archetype that would guide Man in his quest for purpose and truth.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851) is an English novelist famous for writing the earliest examples of science fiction novels and the most celebrated vampires in modern times, “Frankenstein.” Born to the political anarchist philosopher William Godwin and the feminist and Enlightenment philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, Shelley received an informal and unconventional education for the women of the time. She married Percy Bysshe Shelley, who encouraged her writing. Her novel “Frankenstein” was published in 1818, tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, the young scientist who creates a sapient creature in a scientific experiment2. The novel is among the most famous stories that have inspired multiple adaptations and vampire movies. Her second most famous work is probably “The Last Man.” It is an apocalyptic, dystopian science fiction novel, first published in 1826. The events, however, take place in the twenty-first century in Europe, starting in 2037 and ending in 2100 when the world is ravaged by the bubonic plague that led to the near-extinction of humanity.

The selected films are post-apocalyptic action thriller films, a subgenre of science fiction in which the earth and human civilization have collapsed or are collapsing. The stories are built on the last judgment and end-of-the-world plots caused by devastating climate change and pandemics. The selected visual texts are three post-apocalyptic thriller and survival films: “I am Legend” (2007) directed by Francis Lawrence, “The Road” (2009) directed by John Hillcoat, and “The Book of Eli” (2010) by the Hughes Brothers. The characters are involved in an attempt either to stop or deal with the consequences of the apocalypse. The production of this genre flourished since World War II, and since then Shelley’s novels re-emerged. The adaptation of the dystopian world designed in the literary work by Shelley re-evaluates the myth of the last man. I shall argue in this paper that these films adapt the notion of “The Last Man” used by Shelley. The Last Man is revived through dystopian apocalyptic works celebrating the survival of the last man. The purpose of this article is to provide a clear understanding of the nature of the interaction of various signs in selected snapshots to adapt the image of the last man in twenty-first-century cinema. My argument is that image-makers appropriate notions and concepts to adapt them to different eras and not literary works.

Shelley’s works came to prominence and interest in the twenty-first century with the success of vampire movies. Then, COVID-19 came to emphasize the prophecy of the author. In 2020, Eileen Hunt Botting writes that Shelley created “a futuristic” world of chaos and collective anxiety through a global pandemic3. In a different article by the same author, Shelley’s patriarchal world in “The Last Man” is compared to Octavia Butler and Margaret Atwood, where the masculine is the main driving force. Rebecca Barr, for her part, explains that the novel “resonates with contemporary feelings” of climate grief and the desperate circumstances of the twenty-first century. Looking at the review of the literature, critics also consider the issue of faithfulness. With its release, “The Road” attracted the attention of critics looking at the movie as an adaptation of the post-apocalyptic Pulitzer Prize novel by the American writer Cormac MacCarthy. The issue of faithfulness to the novel often preoccupies critics4. “I am Legend” is considered about Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel5 of the same title. Richard Corliss writes, “It’s funny that filmmakers” are interested in Matheson’s works but at the same time “feel the need to ‘fix’ the story and welsh out on its conclusions.” The author wonders if these newly created stories work, using “a qualified maybe” for “I am Legend.”6 Christopher M. Moreman also considers the issue of faithfulness7. “The Book of Eli” received positive responses from both critics and moviegoers.

On the one hand, and despite the fame of the notion of the last man, rare are the works devoted to the adaptation of this notion in cinema as a response to modern world alienation. On the other, adaptation is a motivated process, and a response is, in my view, the best reason to adapt literary works; however, critics are still very limited in their analysis of the filmic text. Shelley’s setting is the twenty-first century, and the films are set and released during the twenty-first century. Thus, the adaptation of the image of the last man has an interesting recurrence that deserves attention.

1. The Theoretical Framework

Two theoretical perspectives are going to be used in this article. The first concerns the adaptation of the image of the Last Man and the Waste Land in the American selected films. The second examines the connotative message behind the popularity of dystopian and apocalyptic novels and the adaptation of the image of the last man, transforming him into “an eternal ‘culture’” (Barthes, 1972, p. 82). These perspectives summarize Noel Carroll’s establishment of the difference between “classical film theory,” in his essay “The Power of Movies,” and the works of André Bazin, who argues that “film image was an objective re-presentation of the past,” and contemporary theories, which reject the idea that film depicts reality. In very memorable words, he states that film “gives the impression of reality itself; film causes an illusion of reality; or film appears natural” (Carroll, 1979, p. 78). In the same vein, Stuart Hall claims that films are not transparent bearers of meaning but “coded” messages that need ways of “decoding” (Hall, 1973, pp. 104–109).

The coding formula implies that the process of filmmaking and adaptation is controlled by many aspects that are related not only to the specific literary work but also, and most importantly, to the context of the adaptation. In her work, “The Theory of Adaptation” (2006), Lynda Hutcheon explains adaptation as a process of transformation that is carefully supervised by filmmakers. What to adapt, who, why, and how, and finally, what is the context of the adaptation, that is, the where and when, are all important aspects that determine the content of the final product more than the original text. She argues that directors act like “interpreters” and “creators” of meaning through “an acknowledged transposition of a recognizable” literary material. The work of the directors and the producers becomes a creative “appropriation”, interpretation, and “salvaging” (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 8). This is on one hand. Julie Sanders, on the other hand, explains the process of adaptation concerning Julia Kristeva’s notion of Intertextuality, which consists of the “interleaving of different texts and textual traditions” (Sanders, 2006, p. 21). In this case, it is not only literary traditions that are intertwined but also the arts. Literary texts are relocated to produce new meanings outside the context of literature. The multimodality of visual texts is one of the most important aspects that encourage the production of authentic literary works of art.

The connotative dimension of visual texts can be explored via Semiotics, a discipline that takes into consideration “the study of signs”. A field that is not limited to the study of linguistic signs but includes other types of communication such as film as multimodal material that functions like a language through shots and scenes that contribute to the construction of the whole. Semiotics also take into consideration the context of production and release. Actually, any film represents a clear and distinguished background and cultural commitment, which influences its content. Every camera move, object included in the scene, and every pose and color involves a message. Both the director and the production company contribute to the film’s multiple interpretations. As a result of the use of these different signs, “reality is not represented as it is but as it is when refracted through ideology” (Comolli & Narboni, 1969, p. 30).

Applying a Barthesian perspective on media texts allows not only an understanding of the sign system at work but also a way to consider the ideological implications of the visual texts. Roland Barthes (1915–1980) was among the first who drew attention, during the 1950s, to the importance of studying media and popular culture substances. Marcel Danesi explains that, together with Jean Baudrillard, Barthes “may have unintentionally ‘politicized’ Semiotics far too much, rendering it little more than a convenient tool of social critics” (Danesi, 2004, p. 33). Currently, Semiotics is one of the best ways of making explicit what is implicit, whether in literature, films, or photographs to investigate the “naturalized” ideologies, to use Barthes’s words.

2. Adaptation as a Response

Sanders and Hutcheon agree on the fact that adaptation is a motivated process that transforms literature into a visual text in different circumstances making “an autonomous creation” (Sanders, 2006, p. 85). Hutcheon explains that, among others, the Cultural Capital and Personal and Political Motives for adaption are the most important ones (Hutcheon, 2006, pp. 91–92). The author then refers to the historical circumstances considering the context of the adaptation (Hutcheon, 2006, p. 142). Sanders calls the final product an appropriation since it is largely defined by the context of the director. This is one of the reasons I consider that adaptation is not an issue of reproduction but of answering and revising the same issue to transform certain realities. At this point, adaptation is a cultural product that uses other cultural aspects; it becomes “the language of the language of culture,” to use Barthes’s words.

In “Rhetoric of the Image,” Barthes proposes a useful theory to deal with image analysis. In this perception, denotation is the first-order signifying system where the literal and obvious meaning appears, whereas, connotation is the second-order signifying system where an additional cultural meaning is implied (Barthes, 1977, pp. 41–42). In the same perspective, he explains myth as “the connotative level of signification, in which cultural and ideological meanings are attached to the sign through codes” (Dicks, 2003, p. 554). He then clarifies that connotation is related to the hidden messages that are ideologically coded. Historical knowledge and contextualization are needed to decode the possible implications lying behind them. Barthes says: “the reading depends on my culture, on my knowledge of the world” (Barthes, 1977, p. 29). This is the reason why the examination of the films cannot be accomplished without referring to the context in which the films are released.

In a broader sense, myth can be explained from different angles. It is a reference to “myths of genealogy” synonymous with stories and legends that include gods and superheroes used to explain natural phenomena like rain, birth, and shaped ancient times (Bronwen & Ringham, 2008, p. 89). Then, there is the cultural theory meaning of myth as a “semiological system” as defined by Claude Lévi-Strauss and Barthes. Myths, in the modern sense, are timeless cultural elements that are incorporated and used in a very natural way in media texts. Barthes’s use of myth is challenging since he sometimes uses it to refer to connotation, ideology, and sometimes discourse and “a type of speech” (Barthes, 1972, p. 107).

I will proceed with my analysis starting with the denotative description of the content of the snapshot then I will refer to the connotative meaning implied. The words of Shelley are used in parallel with selected snapshots as a form of visual connotations. I will refer to the dialogue in the films for emphasis only. Three important similarities are going to be used as illustrations: the image of the wasteland and the last man. I will finish with the twenty-first-century dimension of the issue of the last man like an attempt to restore the father archetype as an example of the mature positive masculine figure.

2.1. The “Waste Land”

Twentieth-century cinema is obsessed with the notion of the end of the world, the “no man’s land,” and the perception that “there are no good men on the road.” This idea is contrasted with the “Paradise Lost” or the “City upon a Hill” that the American founding fathers dreamt of building. The dissatisfaction with modern culture and the loss of the mythical home of the “maternal womb” recalls movies like “The End of World” (1916) and “Planet of the Apes” (1968). This notion of a lost land is dominant in the British gothic novel “The Last Man”. Shelley writes:

“Images of destruction, pictures of despair, the procession of the last triumph of death, shall be drawn before thee, swift as the rack driven by the north wind along the blotted splendour of the sky. Weed-grown fields, desolate towns, the wild approach of riderless horses had now become forms which were strewed on the roadside, and on the steps of once frequented habitations.” (350)

The quotation above refers to a world trapped in fear where death, destruction, emptiness, and desolate towns are invaded by vegetation and animals. The last man is often portrayed in a vacant land. Shelley’s novel takes place in the desolated Europe through different countries like England, Greece to the Ottoman Empire. It is a futuristic vision of a Europe ravaged by the Plague, severe climate change, deserted cold land, population decline, famine, and cannibalism. These descriptions belong, par excellence, to the apocalyptic world of Shelley. Lionel Verney is the last man raised with his sister to embrace civilization thanks to his son’s enemy Adrian Earl of Windsor. He grows to witness the transformation of the world to a muddled grey shadow. He says:

“I contracted my view of England. The overgrown metropolis, the great heart of mighty Britain, was pulseless. Commerce had ceased, seemed already branded with the taint of inevitable pestilence. In the larger manufacturing towns the same tragedy was acted on a smaller, yet more disastrous scale. There was no Adrian to superintend and direct, while whole flocks of the poor were struck and killed.” (229)

Looking at the selected media texts, “I Am Legend” is a 2007 American film directed by Francis Lawrence. Lawrence is also the one behind “The Hunger Games” film series. It is a feature film adaptation of the 1954 novel “I Am Legend” by Richard Matheson. The movie is filmed in New York City. It stars Will Smith as Dr. Robert Neville surviving in an after-apocalyptic world with his pet, the German Shepherd Samantha. The events take place in the year 2015, a world where 99 per cent of the population is infected by the genetically re-engineered measles virus that transformed them into cannibalistic vampires called Darkseekers.

Figure 01: Wall Street in I Am Legend

(Lawrence 00: 02: 31)

The metropolitan center of England, in Shelley’s work, is transformed into the USA. The snapshot above is taken from “I Am Legend”. It represents Wall Street, the busiest street in the world, transformed into a jungle for animals and cannibals. It became the real “ground zero” where human life is impossible, and even the idea of death is distorted to horror since it is linked to cannibalism.

“The Book of Eli” is also an American post-apocalyptic movie produced by Joel Silver and Denzel Washington. It is directed by the American-English screenwriter and game designer Gary Leslie Whitta. The filming takes place in New Mexico. It stars Denzel Washington as Eli. The events take place thirty years after a nuclear holocaust caused by ecocide. Eli is a lonely traveler carrying and reading the Bible, the book that Carnegie wants. Eli is also “the last man,” like a passive figure who stays off the road as he often refuses the company of other people or helps them. In one instance, talking to himself, he says: “It ain’t your concern. Stay on the path. Stay on the path,” repeating this to himself. Eli is a wanderer in a deserted gray land with very rare empty and dangerous houses.

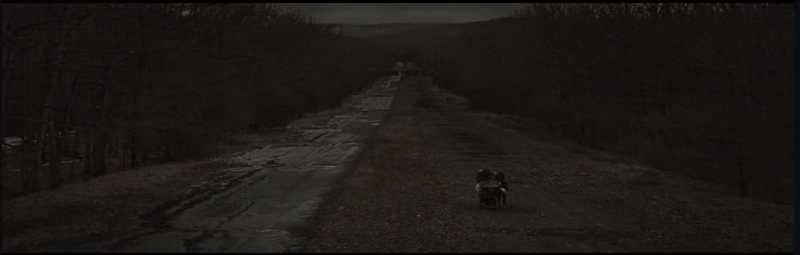

Figure 02: A Destroyed Highway in The Book of Eli

(Hughes Brothers 0 :05 :35 a.m.)

The third movie I’m analyzing is “The Road”. It was directed by John Hillcoat and based on Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. It stars Viggo Mortensen and Kodi Smit-McPhee as father and son, struggling to survive in an apocalyptic world where an unspecified catastrophe led to mass extinction, transforming the survivors into cannibals. They travel eastward in search of the coast. The film was shot in Pittsburgh and later in Pennsylvania, Louisiana, and Oregon. Paul Byrnes describes the film as “relentless but beautiful, harrowing but tender”8. The selected visual texts appropriate Shelley’s apocalyptic and deserted world from a twenty-first-century perspective.

Figure 03: The Empty Destroyed Street in The Road

(Hillcoat 00 :05 :05)

The directors in the three chosen snapshots intend to use the extreme long shot from a low-angle camera gradually raising to become a high-angle camera, especially at the very beginning of the movies. It demonstrates the immensity of the empty world around the protagonist. The low camera angle offers the chaos around the characters power on both the viewer and the characters; the high camera angle allows the viewer to regain control. This explains the reason why the movies start with a low to move to the high. According to Carl Casinghinon, the camera above the subject makes the character or the filmed events seem weak and allows the audience and the protagonist to have control (23). It is also a connotation of finding the road in the middle of chaos, which takes the viewer with the protagonist on a journey to penetrate chaos and establish order.

The four senses that are emphasized in gothic literature are amplified through sound and image in the visual text as “the sound of silence”, in Shelley’s words, imports “the rushing sound of the coming tempest”, “while the air is pregnant with shrieks and wailings, – all announcing the last days of man?” (276) The immense settings exemplified in the bare land, silent cities, an impenetrable void that are all emphasized through the presence of very few isolated characters that are at the mercy of the unknown.

Barthes, in his discussion of “cultural mythologies”, asserts that they are objects that gained a cultural meaning and then used as natural substances to serve an external ideological motivation. It is “a language-robbery” (1972 131). He later gives the example of “the negro saluting the French flag” or “the seasonal fall in fruits prices” to explain that they are not symbols of nationalism, but signifiers used to connote the French imperialism. These “naturalized” aspects “naturalize” the implemented ideology. He adds: “nothing can be safe from myth”, myth in this case is synonyms with ideology. I shall argue that the image of the empty and destroyed cities become mythic and repetitive in the American cinema and television. As if it is, only, in the nothingness that meaning is found.

Shelley describes the twenty-first century as a world of “heart-breaking tales”, of “gasping horror of despair over the death bed of the last beloved”. The protagonist Lionel mentions that with Adrian, his best friend, they drove the empty streets of London, which are “grass-grown and deserted.” Shelley writes:

The open doors of the Empty mansions creaked upon their hinges; rank herbage and deforming dirt, had swiftly accumulated on the steps of the houses; … the churches were open, but no prayer was offered at the altars; mildew and damp had already defaced their ornaments; birds, and tame animals, now homeless, had built nests, and made their lairs in consecrated spots. (291)

These words describing the empty London became a mythic image in the twenty-first century American cinema. These empty streets with the last man tracing his road leaving the familiar world behind and walking through the vacant dangerous streets to look for meaning in the unfamiliar. In I am Legend, Neville has to go back home before sunset to avoid darkseekers. He is “a survivor living in New York City”. The day belongs to the civilized and the night to the cannibals. In The Road, the cold takes over the days and nights. In The Book of Eli, the sun is burning. In both, the empty road belongs to cannibals murdering the last of the civilized men and women. All these men portrayed in the primary sources leave their homes and countries fleeing their lands and searching for safety. Like Lionel, these men come to believe that it is their “destiny to guide and rule the last race of man” (348)

The novel and the selected films portray a “world in severe trauma.” The despair noticed in the world is also translated in the absence of the notion of god and the lack of trust between men and the establishment of terror from “Man” the new god. In The Book of Eli, it is only Eli and Bill Carnegie who know about this “creature called god”. The Bandit leader on the road says upon hearing Eli that he has a message from god: “I got news for you, preacher man. God left these parts a long time ago.” A world without a god is a world of emptiness. In I am Legend, Neville reacts to the fact that everybody is throwing the responsibility on god saying that “It is not God. It is us” trying to imitate the power of god”. In The Road, the man speaks of the god and the presence of his son saying:

All I Know is the child is my warrant and if he is not the word of God, then God never spoke. (Script)

The dystopian empty world has terrible impacts on the characters, psychologically and bodily. Shelley writes in The Last Man:

Adrian welcomed us on our arrival. He was all animation; you could no longer trace in his look of health, the suffering valetudinarian; from his smile and sprightly tones you could not guess that he was about to lead forth from their native country, the numbered remnant of the English nation, into the tenantless realms of the south; there to die, one by one, till the LAST MAN should remain in a voiceless; empty world. (290)

In the selected film texts, Neville knows that he is the last man in New York City so he uses human-shaped dolls in stores to talk to them while shopping. Eli and the man in The Book of Eli and The Road know that they are the last humans to wonder with a purpose other than food so they are ready to die and sacrifice themselves to find a new home. Their struggle is a reminder of Shelley’s words as she writes,

The day passed thus; each moment contained eternity; although when hour after hour had gone by, I wondered at the quick flight of time. Yet even now I had not drunk the bitter potion to the dregs; I was not yet persuaded of my loss; I did not yet feel in every pulsation, in every nerve, in every thought, that I remained alone of my race, – that I was the last man. (290)

This apocalyptic world is not the world of Elle magazine. It is not pure and innocent. It is dangerous and powerful. Barthes explains this what makes Elle world a feminine one and the dystopian world a masculine one where “Man is everywhere around, he presses on all sides, he makes everything exist; he is in all eternity the creative absence” (Barthes, 1972 51).

2.2 The Last Man: the Solitary and the Only Man

Barthes explains that myth has the power to purify things, making them innocent and natural so that the audience can take them for granted. In Mythologies, he writes: “Myth does not deny things; on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, makes them innocent, gives them a natural and eternal justification, and provides clarity, not as an explanation, but as a statement of fact” (143). The principal myth that these films support is that of the image of the hero in the image of the isolated masculine alpha leader tracing his journey to the unknown world leading a life of purpose. Lionel, Neville, the man, and Eli are driven forward by responsibility and the need to achieve a noble aim that is beyond the reach of ordinary men. This leads the analysis to the representation and definition of the hero according to Joseph Campbell: male, heroic, with a readiness to accomplish extraordinary achievements.

The notion of the last man is also famously used by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra as the antithesis of the Übermensch. This conception is contrasted with “the Übermensch” or the superman (06). In a broader sense, the last man, in Jordan Peterson and Campbell’s words, is the hero who struggles to achieve his destiny and face the dragon and chaos; this story is the story of humanity.

Lionel Verney in Shelley’s novel The Last Man, Robert in I am Legend, the man in The Road, and Eli in The Book of Eli all share the reality of being the last man struggling alone in a journey of self-discovery and survival. In Shelley’s novel, Adrian says: “Again I am a solitary man; I will become again, as in my early years, a wanderer, a soldier of fortune” (329). Through the protagonist in Shelley’s novel, we meet an image of the hero warrior facing his interior fears and exterior enemies.

Figure 04: The Last Man on the Front Cover of the Primary Sources: Novel and Poster Teasers

The Last Man Novel Cover9 I am Legend10 The Road11 and The Book of Eli12

The first illustration above on the left is the Oxford cover of the 2008 edition of Shelley’s novel. The three selected posters are teaser posters that appear at the pre-release of the movie. The cover is an extreme long shot of a view of the mountain. It shows a natural view of a covered snow area and greenery. On the green hill, a man is climbing. The iconic image is accompanied by a linguistic message that refers to the author’s name, which is written in red, and under it comes the title of the novel in the house of publication. This cover is a close reminder of Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). The painting, famously, portrays a young man with a stick, wrapped in an overcoat, standing facing an open space of thick fog.

The painting that is often associated with the romantic literary movement becomes an image of the last man facing the void. This cultural element that used to have a clear association is reproduced and adapted to the needs of the time. It converts, as Barthes argues, its particular “historical class-culture” meaning into “a universal nature” (1972 08). His critical look on wrestling, soap powders and detergents, the drinking of wine, toys, and his analysis of the young black man in French military uniform, appearing on the cover of the Paris Match magazine, are all used to elucidate that no matter how simple and innocent the image is, there is always a second level meaning. Hence, his framework, as he confirms, is “an ideological critique” of the language of mass culture (1972 08).

The film posters reproduce or adapt the representation of the last man through the three protagonists: Will Smith, Viggo Mortensen, and Denzel Washington. The shots used in the posters are either long as is the case with I am Legend or medium as is the case in The Road and The Book of Eli. I am Legend is designed on a lighted golden background; The Road and The Book of Eli are grayer. Gray refers to the climatic apocalypse that ruined vegetation on earth and transformed the blue planet into gray. In I am Legend, the near extinction of human life and human activity revived Mother Earth. From the background emerges the last man to survive the apocalypse. In his account of appropriation, Sanders explains how the hero of plays or literary texts is transformed through the image into a “histrionic”, that is exaggerated, character through the process of “defamiliarizing, and displacing.” (56–57) Like Neville in I am Legend, who cannot be infected, the man and Eli are also immune to the evil in the world around them. They are representatives of the man who can swim in dirty waters but remain pure; the last man becomes the Übermensch.

All of the protagonists seem to become mature individuals who have or had families and know two different worlds: order and chaos. The three characters are standing wearing heavy coats, armed, and with a severe posture. Many linguistic texts accompany the iconic text, like the title, the actor’s names, and contributors. Two particular messages are attention-grabbing, the first is “The Last Man on Earth is not Alone” on I am Legend’s poster and “Some will kill to have it, He will Kill to protect it” on The Book of Eli’s poster. The presence of the man’s son in The Road cover brings a stronger and additional meaning to the iconic text and thus to the adapted image. The boy is the heir of the journey.

The reappearance of the same signs reveals the hidden intention of the film. In Barthes’s words, “this repetition […] allows the mythologist to decipher the myth” (1972 119) i.e., it is thanks to the reappearance of such signs that we recognize the connoted ideological meaning lying behind. In other words, the unlimited repetition of the image of the last man surviving is a connotation of the male hero who establishes order, a notion that Peterson refers to in his works Beyond Order (52) and in Maps of Meaning (105). They are “the good guys” who “carry the fire” as the boy describes himself and his father in The Road (0 :24 :00 a.m.).

2.3. The Last Man or the Archetype of the Father

In a world where “Everyone is dead,” Adrian desires a safe place to protect his family. He says:

“I spread the whole earth as a map before me. On none of its surface could I put my finger and say, here is safety. In the south, the disease, virulent and incurable, had nearly annihilated the race of man; storm inundation, poisonous winds and blights, filled up the measure of suffering. In the north, it was worse – the lesser population gradually declined, and famine and plague kept watch on the survivors, who, helpless and feeble, were ready to fall an easy prey into their hands.”

The map becomes a sign of insecurity as it is often laid out in the world of chaos. The selected film uses this image of the desperate man unable to act but then comes to his senses as soon as he remembers his family. Barthes claims that the contextualization of signs is an important stage in understanding their connotation; it becomes potent only if it is used “to refer to the socio-cultural and ‘personal’ associations (ideological, emotional, etc.) of the sign” (1977 135; 1972 162). The lonely last man finds a purpose that would give meaning to his quest. In the three selected films, the image of the last man is associated with the archetype of the father. The apocalyptic world of Shelley is masculine. The absence of the feminine or her limited presence in the novel and the selected films reinforces the position of the masculine as the protector. Once again, the father, the masculine, is the source of Order. The feminine is the source of chaos. The image of the father as a fixer is a mythic image built “on use,” that image-makers “depoliticize according to their needs” (Barthes 1972 144).

The father-son relationship is an important element in the representation of the father archetype. It is a life-crisis ceremony relatable to “the rites of passage,” that guide the path of the son to adulthood. It is connected to the acceptance of the father of the status of “the old man” and allowing the son to leave by blessing him (Van Genne). The father has the power to heal and guide by teaching his son responsibility. However, as explained by David Cheal postmodern families are facing one type of poverty and it is the dominance of solo-mothers and the absence of the father. (58) Norman Denzin, in a pessimistic tone, says: “the typical postmodern child probably does not know his or her father.”13 This breakdown of the traditional family structure led to the almost automatic either emotional or physical disappearance of the father.

Gillette and Moore name the archetype of the father or the father energy as the King energy. It is thanks to the presence of this energy that a psychological balance is created inside the masculine psyche (1992 126). The authors write that the gender identity of the children, males and females, depends on the father. The weak, absent, and immature father cripples the identity. (1990, xv) Men who failed at their fatherhood are “Boys pretending to be men” because “nobody showed them what a mature man is like.” (Ibid 13) The controlling hostile behaviors of these fathers hide vulnerable wounded boys, as well. Thus, the father is the holder of the “map of meaning” that the children need. The death of the father causes a “life-threatening imbalance in the powers of the constituent elements of experience.” (Peterson 126) Adapting the dystopian world is a reaction to the shaking in the gender balance and roles in the West and in the world.

Figure 05: Restoring the Image of Father Archetype through the Last Supper

(Hughes Brothers 0 :44 :51 a.m. —Lawrence 01 :07 :31 – —Hillcoat 0 :55 :10 a.m. –

The adverb “last” in Shelley’s novel becomes associated with “moments of happiness”, last hope, last bed, last words, last sun rays, drops of water, and the last pieces of food and last traces of humanity, and last moments in a familiar world turning into the antithesis of civilization. It is, most of all, the last of the “race of Englishmen” and the “civilized men.” These “last times” are appropriated in the chosen movies through “The Last Supper” scene. It is the last attempt to restore faith in civilization, in the notion of the family model, and in the image of the father archetype. It is the representation of the last moments of happiness. Shelley writes: “The last hour of many happy ones is arrived, nor can we shun any longer the inevitable destiny. I cannot live – but, again and again, I say, this moment is ours!” It is also the last prayer where each one “held the hand of his last hope.”

Flashbacks in “The Road” and “I am Legend” are a reminder that these men are husbands and fathers. Neville rediscovers the father role after meeting Anna and her son Ethan. When lifting him to sleep in his daughter’s room, he says: “He is heavy”. The scene is filmed through a close-up with Ethan sleeping while putting his arms around his father.

The death of the father marks the final stage of the passing. The boy and the young are officially carriers of the fire of life. In “The Road,” The father refers to the child as “the word of God.” The fear of any moment being the “last” amplifies the power of death but also the attachment to life and love. “This, my friend, is probably the last time we shall have an opportunity of conversing freely.” The man in “The Road” teaches his son that death is not “the worst state of savagery” preparing him for the day he is not with him. The Presence of Solara, the Boy, and Ethan in the movies brings hope and keeps the father; or the male adult moving on to a safer land. Shelley writes: “If manly courage and resistance can save us, we will be saved. We will fight the enemy to the last. Plague shall not find us a ready prey; we will dispute every inch of ground; and, by methodical and inflexible laws, pile invincible barriers to progress of our foe.”

Teaching the goodness of the human spirit is transmitted from the father to the son in “The Road.” He clearly explains that hunger is not a reason to transform into cannibals. The mise-en-scene represents a mythological fight between good and evil where the father is the main representative of the powers of goodness. In this context, Lionel, in Shelley’s novel, mentions that Adrian is the one who taught him that “goodness, pure and single, can be attribute of man.”

It is in this perspective that Barthes clarifies that during critical times and within new circumstances, a new meaning or “a whole new history is implanted in the myth.” In the Barthesian view, myth is the third level of meaning where the ideological intentions of the bourgeoisie become apparent. Nevertheless, Barthes speaks of cultural myths that are used as instruments to transform “history into nature.” Thanks to myth, he adds, everything is “immediately frozen into something natural.” To clarify this point, Daniel Chandler says that “Barthes did not see the myths of contemporary culture as simply a patterned agglomeration of connotations but as ideological narratives.” Working on this argument, one can say that the different versions of the last man as dealt with in the selected films are copies based on material that has been worked on several times. Likewise, “mythical speech is made of a material which has already been worked on so as to make it suitable for communication.”

One important component of the selected visual texts that appear in the novel is the dog pet. Samantha is Neville’s Dog Pete, a German shepherd that belongs to the family. Neville keeps the dog when he separated from his wife and daughter who died shortly after. She becomes Neville’s only family. Neville and Samantha develop a very close relationship that when the dog dies, Neville feels desperate and throws himself into the night to the dark seekers. A nameless dog appears also in “The Road.” The dog becomes a sign that connotes safety and hope. The animal is also an important character in Shelley’s novel:

“My only companion was a dog, a shaggy fellow, a half water and half shepherd’s dog, whom I found tending sheep in the Champagne … from that day has never neglected to watch by and attend on me, and from that day has never neglected to watch by and attend on me, showing boisterous gratitude whenever I caressed or talked to him. His pattering steps and mine alone were heard.”

Conclusion

Shelley’s dystopian novels are the fertile background that makes up successful cinematic adaptations and offer a chance to question modern lifestyle aspects. Contrary to the rejection that these novels met during the 19th century, these dystopian imaginary worlds are adapted into modern horror, incorporating the gothic and the apocalyptic visions of the world that are often met with positive reviews and enormous box office revenue from audiences.

Shelley’s novel is revolutionary in its portrayal of the twenty-first-century apocalyptic world. The image of the last man is the image of the masculine hero that has been invading the screen since the Second World War not just through the horror genre but also in drama, action, and comedy. The adaptation of “The Last Man” sheds light on the representation of the image of the father and the revaluation of the postmodern relations between the mature and the immature masculine. It is also an opportunity to produce new myths and use them. The last Man and the wasteland are among the most famous images that reappear in literature and visual texts. They are the new myths that are purposefully built up and that Barthes allows through his theory to study and examine these myths as ideologies that transform the language of culture.

The last man is the lonely man, a modern “mythic hero” who is “lost in translations” but struggles to make sense of this void. He is also a survivor who struggles against the world and himself. He becomes a representative of the unknown that nobody understands and dares to come near and then, sometimes, the murderer, as is the case of Eli. The last man is the supportive friend, but then the father initiates the son and offers him a positive masculine archetype. The loss of faith in humanity and the shaken belief in the notion of masculinity gave birth to the necessity to establish the positive masculinity that brings order. The post-apocalyptic movies use the image of the last man to restore the image of the heroic father.

Adapting the image of the last man in American cinema from the British novel by Shelley is an artistic response to the despair and the sense of mythlessness that the modern Man is going through. The studied movies attempt to restore faith in Man, god, and the mature masculine and the father as the protector and the savior. The adaptation of literary works and the question of faithfulness in the twenty-first century is debatable. However, it is adapted and appropriated as the representation of the lost world of the last man through the post-apocalyptic cinema productions of the twenty-first century. Shelley’s gothic and dystopian world is an avant-gardist perception of an apocalyptic empty world destroyed by the plague. Visual arts celebrate literary works and transform certain figures into myths. The last man becomes the mythical figure of twenty-first-century cinema that is a representation of the modern hero. The male hero who acts alone during the plague transforming Europe to a vacant land, which is simply a prophecy of the COVID era.