Introduction

Macrosomia is defined as a term birth weight greater than or equal to 4000g. Its frequency worldwide is 8% [MERGER R. et al; 1995], and in Algeria, it is 14.9% [AI KOYANAGI et al; 2013]. In France, it is 6.4% [MERGER R. et al; 1995], in the United States 7.8% [NOGON JJ. et al; 1990], in Morocco it is 7.68% [Mounzil C. et al; 1996], and in Tunisia 6.8% [OUARDA C. et al 1989]. This phenomenon becomes a public health problem due to the poor prognosis during childbirth, whether for the mother (tears: vulvar, cervical, subperitoneal; hematomas: vulvar, vaginal, subperitoneal; hemorrhages; endometritis) or for the newborn (traumatic: shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, fractures, sero-sanguineous boss, hemorrhages; neurological: asphyxia; hemodynamics: respiratory distress syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; metabolic: hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyperbilirubinemia, polycythemia). In addition to complications during delivery, these macrosomic newborns could later develop chronic pathologies (arterial hypertension, diabetes, Cushing’s syndrome) that can be avoided with proper care from birth and for their mothers before pregnancy.

1. Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive retrospective study conducted on newborn records at the neonatology department at EHS NOUAR FADILA in Oran. It involves 40 cases of newborns born from January 1 to March 31, 2019. The statistical analysis was performed using Epi Info software for calculations and Excel 10 for graphical representations.

2. Results

-

Frequency: Among the 40 files studied, 11 are considered macrosomic, accounting for 27.5%. We found a very high frequency, which could be due to the small sample size.

-

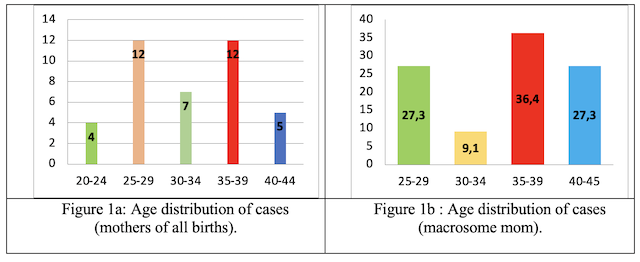

Maternal Age: The peak is equal for the age groups [25–29] and [35–39] (Fig.1a). For mothers with macrosomic newborns, 63.5% are over 35 years old (Fig.1b). Tables I and II show the age characteristics of mothers.

-

Place of residence: Mothers hospitalized at EHS are mostly residents in Oran (52.5%). (Fig.2 a- 2b).

-

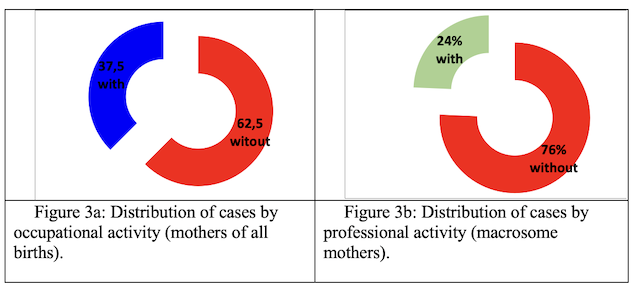

Professional activity: Mothers without a profession had more macrosomes than working ones. (Fig.3a-3b).

-

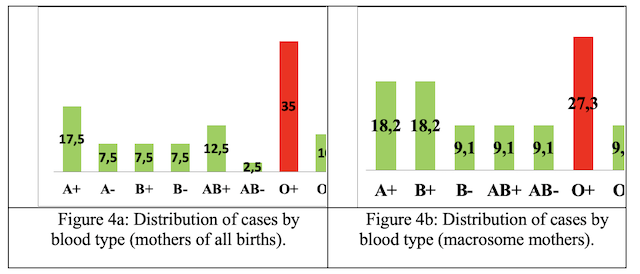

Blood types: Mothers with blood type O+ are in the majority, either for the mothers of all births (35%) (Fig.4a) or for those who gave birth to macrosomes (27.5%) (Fig. 4b)

-

Existence of previous diabetes: One-fifth of mothers are diabetic (mothers of all births) (Fig.5a), and 54% of mothers given macrosomes are diabetic (Fig.5b).

-

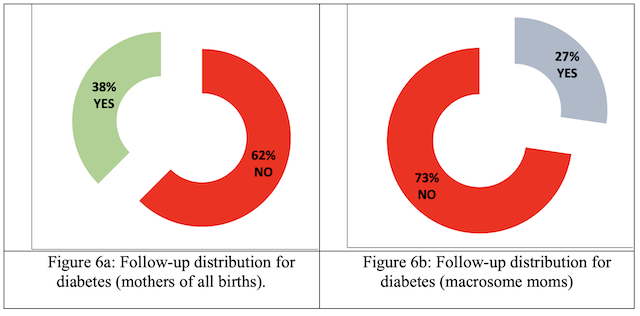

Followed for diabetes: Most diabetic mothers are without therapeutic follow-up either for the mothers of all births (62%) (Fig.6a) or for those who have given birth to macrosomes (73%) (Fig.6b).

-

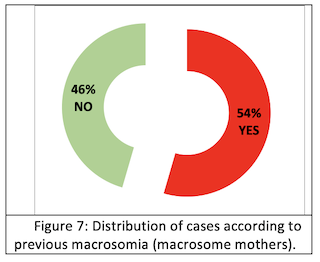

History of macrosomy: More than half (54%) (Fig.7a) of mothers who have given birth to macrosomes have a history of macrosomia.

-

Current HTA: The notion of hypertension is low for the general population and also for those who have given macrosomes) (Fig.8a-8b).

-

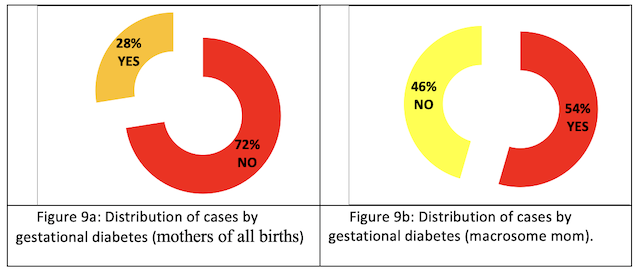

Gestational diabetes: More than half (54%) of mothers who gave birth to macrosomes developed gestational diabetes (Fig. 9 a-9b).

-

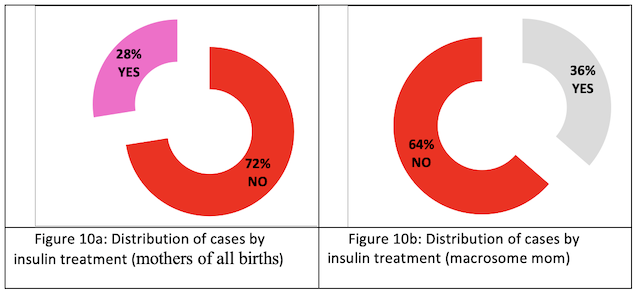

Insulin treatment: Insulin treatment was not given to all diabetic mothers (72%) (Fig. 10a). More than a third of diabetic mothers of macrosomes were treated with insulin (Fig.10b).

-

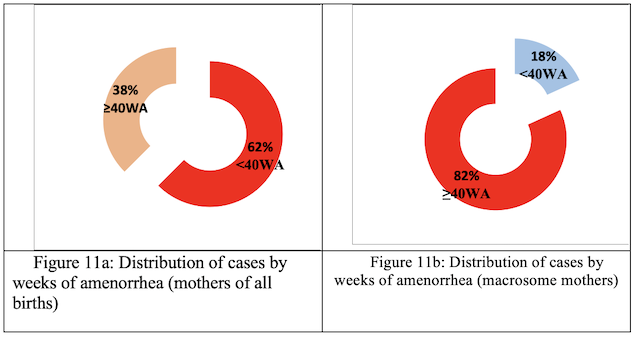

Term (WA): More than 80% of mothers who gave birth to macrosomes went beyond term. (Fig.11 a-11b)

-

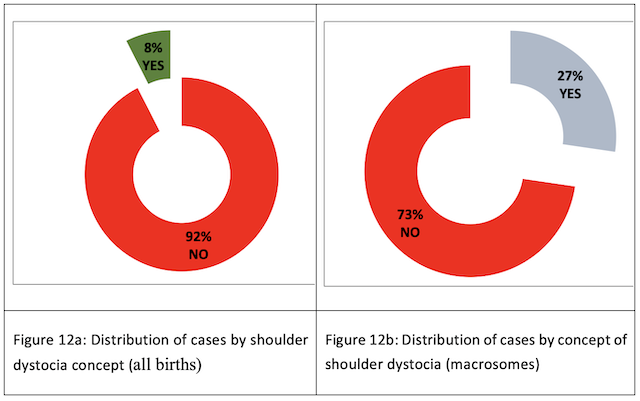

Shoulder dystocia: Shoulder dystocia in all births is minimal (8%); it is found much more commonly in macrosomes (27%) (Fig. 12 a-12b).

-

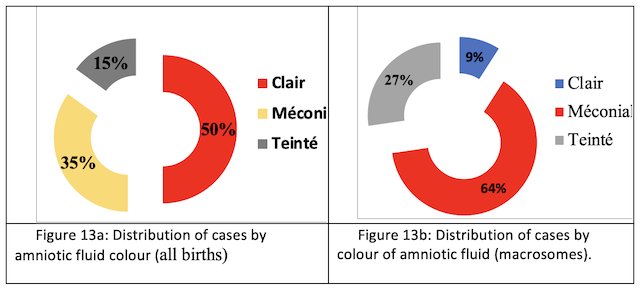

Amniotic fluid (AF): Amniotic fluid is predominantly clear in all births (50%) (Fig.13a), while meconium is present in neonatal macrosomes (64%) (Fig.13b).

-

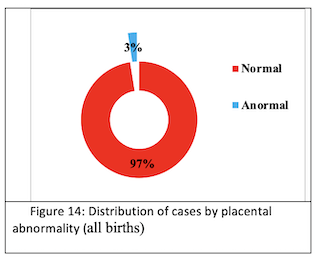

Placental abnormality: Placental abnormality is rare for all newborns (3%) (Fig.14) and macrosome neonates (0%).

-

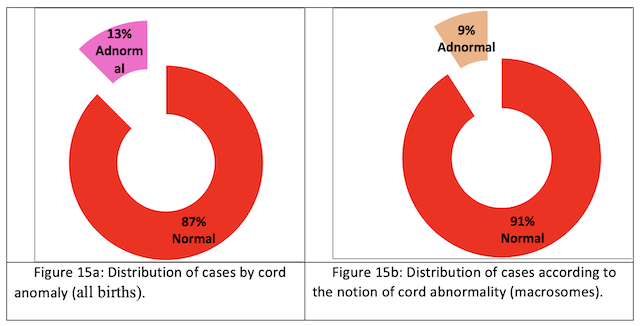

Cord anomaly: The normal state of the umbilical cord is more commonly observed than the abnormal state for all births (87%) (Fig. 15a) and for newborn macrosomes (91%) (Fig. 15b).

Ways of delivery: The majority of deliveries are via the vaginal route for all births (60%) (Fig. 16a), while 73% of mothers with macrosomic infants gave birth by cesarean section (Fig. 16b).

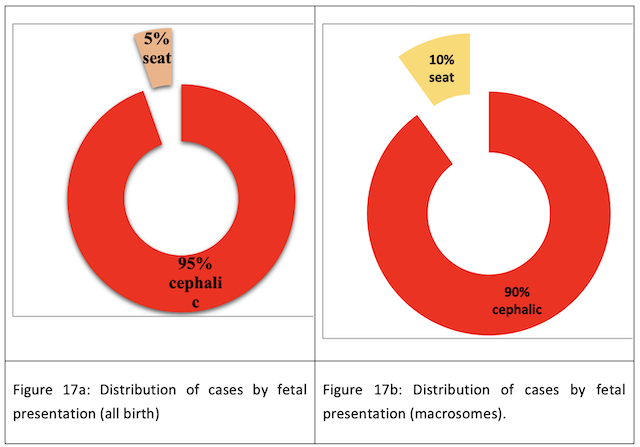

Presentation: The majority of cephalic fetal presentation is observed for all births (95%) (Fig. 17a) and for macrosomic births (90%) (Fig. 17b).

-

Gender: The sexes are equal for all births; however, the male sex is in the majority among newborn macrosomes (64%).

-

Height (cm): the macrosomes are all 49 cm or larger in size. (Tab III, Tab IV)

-

3.21. Head circumvention (cm): The macrosomes all have cranial circumferences greater than or equal to 34 cm. (Tab V, VI)

-

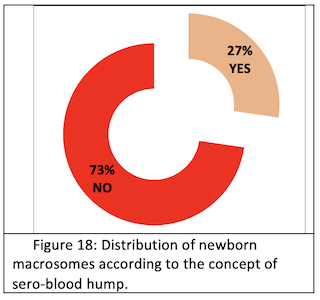

Sero-sanguine bump: Serosanguineous bumps are found in 27% of macrosomes. (Fig.18)

-

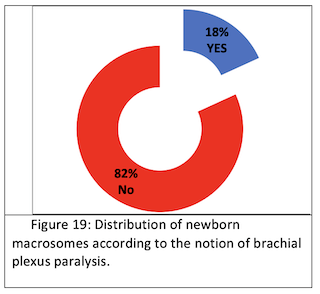

Brachial plexus paralysis: We found 18% brachial plexus paralysis. (Fig.19) We found 3% of neonatal suffering and resuscitation.

-

Respiratory distress: We found 27% respiratory distress. (Fig.20)

-

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: We found 9% hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Fig.21).

-

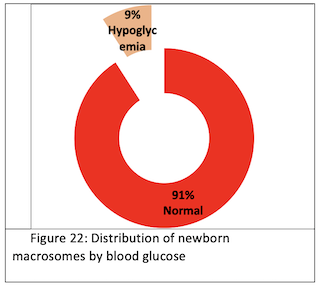

Blood glucose (g/l): We found hypoglycemia in 9% of cases (Fig. 22).

-

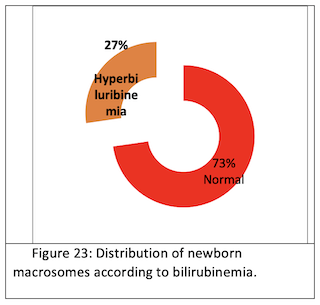

Bilirubinemia: We found 27% hyperbilirubinemia. (Fig.23)

3. Discussion

Fetal macrosomia lacks a universally accepted definition, leading to a prevalence range of 0.5-15% depending on the criteria — birth weight above 4000 g, 4500 g, 5000 g, or beyond the 90th percentile for gestational age. Our study aligns with findings by Martin et al. (2023), showing a 10% incidence of macrosomia, contrasting with lower frequencies reported elsewhere. The weight distribution in our study, predominantly between 4000 and 4400 g in 80% of cases, mirrors the majority consensus in the literature.

Consistently with Lee et al. (2022), we observed a higher incidence of macrosomia in males (58%) and a predominant cephalic presentation (95%), paralleling several other reports. Our cesarean rate of 45.72% diverges from the lower rates found in broader research, such as the cross-cultural examination by Wang et al. (2023). Normal delivery was estimated at 53%, with forceps usage being minimal in our series.

The maternal age profile, with the majority over 29 years, correlates with data from several authors and studies like that of Essel et al. (1995), which showed a small percentage of mothers under 20 years and over 40 years. Parity appears as a significant risk factor for fetal macrosomia; our study’s finding of a high percentage of multiparous mothers (47.27%) is supported by similar findings. The ACOG underscores the history of macrosomia as a highly predictive factor, which is mirrored in our study with a 14.16% rate of women with a prior macrosomic birth, supporting the diverse literature on the topic.

Diabetic mothers comprised only 1.81% in our series, a figure that aligns with some studies like BISH’s but stands in contrast to higher percentages found in others, such as Beta’s research (2019). Maternal obesity emerged as a key factor, with obese women having a fourfold increased risk of fetal macrosomia, echoing findings by Pillai et al. (2020).

Regarding neonatal outcomes, our study’s high prevalence of neonatal infections (88%) and shoulder dystocia deviates from the lower incidences reported by Rodriguez et al. We reported no neonatal mortality, which is not consistent with the literature, where studies like Abdallah’s and Ndiaye et al.’s reported mortality rates of 10% and 12%, respectively. The study by Beta et al. (2019) also indicated a significant mortality rate of 6%, highlighting that birth weights exceeding 4500 g substantially heighten risks for both maternal and neonatal morbidity, as confirmed by Kim et al. (2023).

To address the issues identified in our study, it would be necessary to adapt prevention strategies and manage them. These strategies are :

-

Identification and Monitoring of High-Risk Pregnancies: Assessing maternal risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, and advanced age is essential. Regular monitoring of these high-risk pregnancies can help prevent macrosomia.

-

Control of Maternal Weight and Diet: It is important to advise pregnant women on a healthy diet and appropriate gestational weight gain. Tailored nutritional guidelines can help prevent excessive fetal weight.

-

Management of Maternal Diabetes: Strict monitoring and control of blood glucose levels in pregnant women, especially those with gestational or pre-existing diabetes, are crucial. This may involve adjustments in diet, exercise, and, if necessary, medication. These management strategies are :

-

Planning of Delivery: The choice of delivery method should be individualized based on the estimated fetal weight, maternal health, and obstetric history. Cesarean section may be considered in cases of severe macrosomia.

-

Management of Labor Complications: Training medical staff in managing complications such as shoulder dystocia is essential. Appropriate delivery strategies should be in place to minimize the risk of birth trauma.

-

Postnatal Care: Close monitoring of the health of the newborn and the mother after delivery is important, especially in cases of complications related to macrosomia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study highlights the varied and complex nature of fetal macrosomia and its management. Despite the absence of a universally accepted definition, the correlation between macrosomia and maternal factors such as age, parity, diabetes, and obesity is evident. Our findings of a higher incidence in male infants and the predominant cephalic presentation align with other reports, yet our higher cesarean rate stands out from broader research findings. The significant impact of maternal obesity on the risk of fetal macrosomia, as seen in our study and supported by others, emphasizes the need for targeted prevention strategies, including monitoring high-risk pregnancies, controlling maternal weight and diet, and managing maternal diabetes. Additionally, the discrepancies observed in neonatal outcomes, such as the high prevalence of neonatal infections and shoulder dystocia in our study, underscore the importance of careful delivery planning and postnatal care. Our study underscores the importance of a nuanced approach to the management of macrosomia, which addresses not only the immediate clinical challenges but also considers the broader implications for maternal and neonatal health. As such, a multifaceted strategy involving both prevention and management tailored to individual cases is crucial to effectively address the complexities of fetal macrosomia.