Introduction

EFL teaching has witnessed a number of considerations in terms of the personal and affective factors affecting the second/foreign language learning. Various researchers have revealed significant relationships between foreign language performance and different learners’ variables; namely, aptitude, attitude, motivation, learning styles, and learning strategies. Among the various characteristics identifying foreign language learners, empathy has recently been given credit in research studies mainly with the emergence of emotional intelligence. It has been assumed that empathy can play an important role in foreign language learning and develops affective and interpersonal skills to comprehend and adopt different views of different people.

I vividly recall the number of misunderstandings and clashes in my EFL classrooms when discussing or giving kinds of debates especially about some specific cultural or religious matters. I often tried to explain to my students that they have to respect the others’ points of view and thoughts which imply empathy. The current paper is then an attempt to define empathy and its role in an EFL classroom, and why it should be developed at learners to favour their personal growth and at the same time to improve their language achievement. In addition, the importance of empathetic teacher to act as a model is also emphasised.

In this respect, the current paper has been carried out to study empathy and EFL learning at the level of ENS (Ecole Normale Suprieure) of Oran, and to explore how the teacher’s empathy as well can influence the learning/ teaching process in general and learners’ engagement in particular. Therefore, the main research questions the researcher tried to answer are the following:

-

What are the EFL learners’ perception towards empathy ?

-

To what extent does empathic teaching influence EFL learners’ engagement in their classrooms ?

Accordingly, It is assumed that through the study EFL learners would reveal positive perceptions towards empathy; and they would be zealous to engage in their language learning when empathic attitudes are displayed. That is, empathic teaching might affect students’ involvement and social interactions.

1. Empathy as a human characteristic

A common definition provided by the dictionary refers to empathy as “the psychological identification with or vicarious experiencing of the feelings, thoughts, or attitudes of another.” Empathy is also perceived as the ability to put oneself in somebody else's shoes as advanced by Krznaric (2012) who defined empathy as: “… the ability to step into the shoes of another person, aiming to understand their feelings and perspectives, and to use that understanding to guide our actions. That makes it different from kindness or pity.” (p. 78).

Accordingly, empathy involves various dimensions as it encompasses affective, cognitive, moral, and behavioural aspects. People with empathy are understanding and open; they understand and accept differences in thoughts, beliefs, cultures, and religions and then are receptive and unprejudiced. That is, the importance of understanding and accepting the ‘other’ is stressed by Krznaric (2012) as he maintains that empathic individuals can identify feelings, attitudes, situations, and perspectives; as such they can admit and appreciate the others’ interests and concerns. As a result, they can develop curiosity about foreigners, tolerate social change and expand a more responsive awareness.

Furthermore, Guiora (1972) described empathy as “a process of comprehending in which a temporary fusion of self-object boundaries, as in the earliest pattern of object relation, permits an immediate emotional apprehension of the affective experience of another, this sensing being used by the cognitive functions to gain understanding of the other.” (p. 142). Indeed, as a human aspect, empathy is required in all situations of life in which the human being needs to be able and ready to understand the others to manage communication and work with different individuals. It is deemed a vital trait of human resources professionals (Haberman, 2013). For instance, in the provision of patient-centred care Mercer and Reynolds (2002) argued that empathy refers to the capacity to understand the patient’s condition and feelings; to communicate such understanding and examine its certainty; and act on that understanding with the patient. Thus, the three key actions- understanding, communicating, and acting are the basic elements for an effective relationship. Moral, emotional, cognitive, and behavioural elements of empathy provide a professional satisfaction. (Stepien and Baernstein, 2006). In this respect, empathy as a complex notion to be understood should not be confused with sympathy that is a feeling of pity for a person experiencing a negative circumstance.

2. Types of empathy

Besides the fact that there are different elements that make up empathy, there are also different types of empathy as advanced by many psychologists; namely, cognitive, affective, and compassionate.

2.1. Cognitive empathy

Also known as ‘perspective-taking’ or ‘empathic accuracy’, it regards empathy as a cognitive skill in the sense that it refers to the ability to identify and understand the others’ emotions, thoughts and perspectives without necessarily feeling their emotions. Thus, it involves a logical and rational position. Generally, this kind of empathy is beneficial for debates and negotiations- when understanding the different views avoid tensions and clashes. Moreover, empathic people can acknowledge and value concerns of the others; they raise their curiosity and interest about foreigners, open up, and develop resourceful insight of the different cultures. (Krznarik, 2012). In this respect, empathy is crucial to avoid any established stereotype or determined prejudice.

2.2. Affective empathy

Also known as emotional empathy refers to sensations and feelings in response to the others’ emotions. Emotional empathy is also known as personal distress or emotional contagion; this is explained by the degree empathic people can literally feel the others’ good or bad situation as if they have themselves experienced it, and share their distress, suffering and joy. As Goleman (1995) pointed out, this type of empathy is connected with mirror neurons in the brain. Due to this system, people mirror what they see in others in terms of circumstances or emotions. The first example of affective or emotional empathy is reflected between a child and his/her mother and with our loved ones. For instance when the baby cries and his mother smiles and chills him up with a hug and then the baby gives a smile back. This kind of empathy generates behaviours to share the others’ feeling of pain. This tightens an affective affinity between individuals.

2.3. Compassionate empathy

“With this kind of empathy we not only understand a person’s predicament and feel with them, but are spontaneously moved to help, if needed.” Goleman (1995). This type of empathy is considered as optimal in the sense that it is a balance between the cognitive and affective empathy; when the former fits situations of workplace and health care, and the second best suits responses with children and for beloved individuals; compassionate empathy provides a coherence of the types. Goleman (1995) explained: “Compassionate empathy honours the natural connection by considering both the felt senses and intellectual situation of another person without losing your centre”. (p. 23). In this respect, the sensitivity of the heart is linked to the reflection of the brain to react with a perceptive understanding.

Furthermore, studies in neuroscience have indicated that the human brain is hardwired for empathy. According to Warrier & al (2018), the different components of empathy relevant to thoughts, feelings, and actions are sustained by different brain networks. Neuroscientists explained that when individuals see others’ actions, they involuntarily react as ‘actors’ not ‘observers’ through what is called mirroring; that is, the use of the mirror neuron system. In this respect, Iacoboni (2008) clarified: “empathy occurs via the minimal neural architecture for imitation interacting with regions of the brain relevant to emotion. All in all, we come to understand others via imitation, and imitation shares functional mechanisms with language and empathy.” (p. 57).

Finally, individual irregularity in empathy has been demonstrated to be highly recorded in mature people and females (Fields & al., 2011). However, research has proved that the degree of empathy is not linear; it can diminish or increase during the lifetime. (Konrath, Chopik, Hsing, O’Brien, 2014)

3. Empathy and Emotional Intelligence

The notion of emotional intelligence (EI) has recently emerged to witness an important renown in many fields. Indeed, EI is crucial in our daily life and for human relationships, it encompasses intrapersonal and interpersonal relations. Emotional intelligence was perceived as "the ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions." (Salovey and Mayer, 1990).

In fact, the principle of EI was first noticed in the work of Thorndike in the 1930s within the aspect of ‘social intelligence’ which refers to the skill to get on and cope with other individuals. Later, the 1950s witnessed the emergence of the Humanistic Approach, and through this perspective, scholars like Maslow gave a great consideration to different means that could help the individual build emotional potential. By the mid 1970s, another distinct notion favoured the development of emotional intelligence in Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory. In his book “Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century” Gardner (1999) asserted that the human being does not possess one single ability but a multitude types of intelligence. Precisely, there are eight:

-

Linguistic intelligence: the ability to use proficiently words in both speech and writing; to memorize names, dates, and places; create language and convey messages through words, discussions and humour.

-

Visual or spatial intelligence: the competence to discern locations and to build mental representations and spatial understanding.

-

Logical-Mathematical: the ability to use logic, reasoning and systems; also effectively analyse scientific rationale, productive and deductive thinking.

-

Kinesthetic (physical or bodily): it is related to the use of hands, sense of touch, body language and sport.

-

Auditory-musical: the ability of using sound and music; recognition, formulation and modification of musical arrangements.

-

Interpersonal and social: the ability to adapt easily to any type of social situation, the perception of feelings and motivation of others (having empathy with others), communication and delivery in a group with others

-

Intrapersonal: the competence of the self-study, self-knowledge, understanding of one’s feelings and motivation to behave based on this awareness.

-

Naturalistic ability to differentiate between natural phenomena of the world and their evaluation.

Hence, within this framework, emotional intelligence is perceived as the ability to (a) to assess one’s feeling, (b) to understand the others and to feel them, and (c) to adapt one’s behaviour and emotions in an effective manner (Goleman, 1998). Such an approach raises the aspect of empathy and its social dimension, as it acknowledges that this kind of awareness is beneficial to improve interpersonal skills: "People who are empathic are more attuned to the subtle social signals that indicate what others need or want." (p. 89).

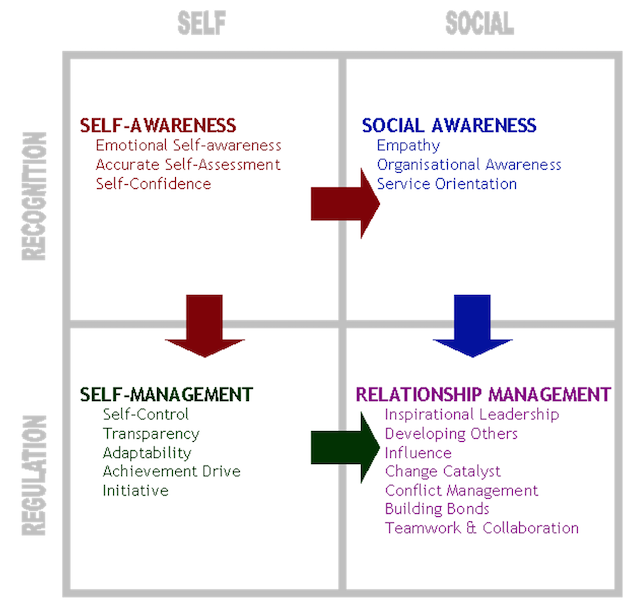

Furthermore, the concept of Emotional intelligence has also been attributed the abbreviation of EQ- Emotional Intelligence Quotient, which has been considered equal or sometimes more influential than IQ – Intelligence Quotient. They are perceived as two distinct capacities as Goleman (1999) claimed that “the most intelligent persons among us could be drown into an ocean of undisciplined impulses and unbridled passions”. In this sense, Goleman considered EI as a dimension that involves key elements ; namely, self-awareness, self-regulation, empathy, handling relationships, and motivation.

FIG 1: Components of Emotional Intelligence (Goleman 1999)

Within this scheme, empathy is a central element of emotional intelligence as an intrinsic ‘human skill’ that has a potent role in making individuals better and more successful in their relationships; and also in their professions related to social interactions such as nursing, teaching, and administration. In this sense, the focus is on the social dimension of empathy: “Empathic people are more attuned to the subtle social signals that indicate what others need or want." (Goleman, 1998, p. 69)

4. Empathy and language learning

In terms of what has been stated earlier, empathy is considered as a key element in interpersonal relationships; Brown (1994) defined it as “the projection of one’s own personality into the personality of another in order to understand him or her better.” He claimed that empathy can be developed and exercised through two important elements; the first concerns awareness and knowledge to one’s own feeling, and the second is recognition with another individual. As such, empathy would lead to a balanced harmony of different individuals within society, and “facilitates communication, since communication requires people to ‘permeate’ their ego boundaries so that they can send and receive messages clearly.” (Chen, 2008, p. 142).

When applied to second/foreign language learning, empathy is perceived as an effective intercultural communication. In this regard, Gudykunst (1984) explained that efficient people in communicating with strangers do not use the attitude and view of their own culture but the others’ cultural perspectives, he argued that they use a ‘third-culture perspective’ which plays the role of an emotional and psychological connection between their cultural perspective and that of the strangers. Furthermore, Gudykunst (1984) asserted that when individuals develop this attitude they tend to understand and comprehend the others’ statements and then evaluate their behaviour; that is, they try to interpret their interlocutors’ unfamiliar behaviour instead of judging them as bad or meaningless; this perspective leads them to build effective relationships with others.

Accordingly, if the same aspect is applied in classroom interaction, empathy would help students to acknowledge and respect the “other” by understanding perspectives different from their own. In this respect, Fernandeze (2017) advanced: “Perhaps the greatest power of empathy in the classroom is that it reminds our students that the burdens of their own struggles do not relieve them of the responsibility to see and to acknowledge others in theirs.” (p. 196). In this respect, language learners who are conscious and responsive to their classmates’ feelings are likely to be ready for risk-taking and communicate with others, Chen (2008) affirmed that “highly empathic L2 (Second Language) learners are more likely to identify with the communicative behaviour of users of the target language.” (p. 142), consequently, students would feel less anxiety to be judged and then would engage more in the classroom activities which would enhance interpersonal, cultural, and social awareness. (Maranville, Lynch, Kay, Goldfarb & Engler 2012).

In accordance with what has been stated above, in a previous research in an Algerian context, empathy has been revealed to be a helpful feature present at high risk-taker students in their EFL oral class (Benosmane, 2018). In fact, among fifteen cases under study, three raised the aspect of empathy (besides other internal and external factors) to be beneficial for their oral interaction. Indeed, those cases were classified in the study as high risk-takers. They were aware that an appropriate communication involves empathy, and the right feeling towards the others. Empathy was also affirmed by a strong motivation to communicate and share points of view. It was revealed as a metacognitive consciousness about how to deal with the interlocutor, and how to manage a suitable interaction; a key aspect in any type of communication: to understand and to be understood. Some other cases considered the classmates and teachers’ attitudes towards their responses and mainly their mistakes, and the type of feedback they were provided. This last point encompasses teachers’ empathy which is dealt with in the current study.

In this sense, empathy in language learning involves that of learners as well as that of teachers. Understanding the others is favourable for language learning. Thus, inciting students to develop the sense of acuity towards each other might be helpful to encourage classroom communication through a variety of activities.

5. Teacher’s empathy

As stated in the previous sections, empathy tends to be the basis of emotional intelligence, and vital for a safe self-regulation as well as interpersonal relationships; in addition, it is favourable in the educational setting to set healthy connections between the members of the classroom. Thereby, the teacher needs to show and model empathy in front of his leaners. In his investigation about ‘What makes a good teacher ? Harmer (2001) found out that among the listed characteristics and skills of a good teacher, numerous respondents have raised teacher’s empathy, and how they talk to their students: “the way that teachers talk to students- the manner in which they interact with them- is one of the crucial teacher skills, but it does not demand technical expertise. It does, however, require teachers to empathise with the people they are talking to. (p. 3)

Indeed, teacher’s role is not limited to provide knowledge but to care about his learners and their learning; empathic teachers address the variety of learners and help enhance their involvement in the classroom. Teacher empathy tends to make teachers consider their teaching, behave with objectivity, and treat students equally. In this respect, Fernandeze (2017) argued:

“When we teach with empathy we are choosing to see all of our students, perhaps for the first time. From that perch, we can champion not only those who are doing well but also those who are struggling….Empathic teaching helps us to reach the whole class, including those at the margins and those who appear to be either left out or left behind.” (Fernadez, 2017, p. 695)

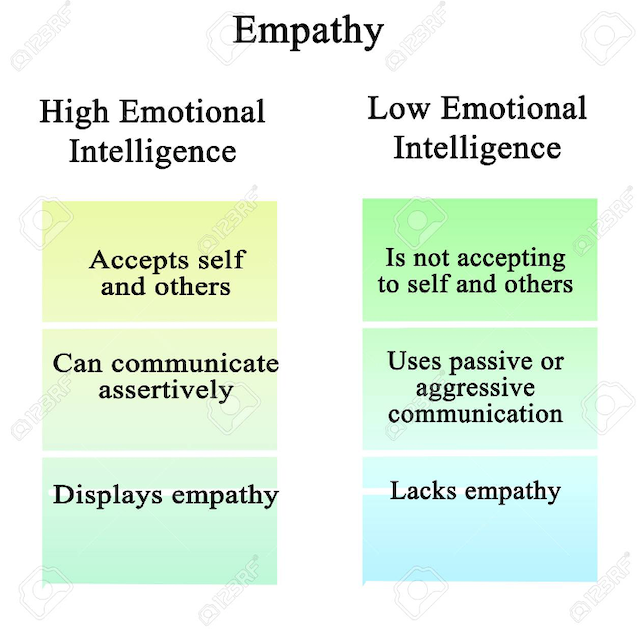

Furthermore, teacher’s empathy has been proved to be helpful in many ways. First, it is considered as a requisite teacher’s behaviour favourable to create strong relationships in an inclusive classroom. In addition, empathic teacher can avoid oppressive behaviours and cruel practices in his classroom; and consequently, create a homogeneous class in terms of mutual care and respect. The act of empathising can be communicable- teacher empathy will encourage the effort of empathy among classmates. Derelli and Aypay (2012) advanced that student’s empathic tendencies were conductive to develop responsibility, friendship, pacifism, respect, honesty, tolerance, and human values of collaboration and cooperation which are practical for group or team work. This is explained in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: Empathy and Emotional Intelligence

For this to happen, teachers need to plan and implement adequate teaching strategies which entails pedagogical content knowledge, classroom management, and emotional training including values that contribute to the holistic development of learners – intellectual and personal. Empathy needs to be developed and modelled by teachers. Cooper (2011) suggested that teachers can build up different types of empathy; namely, fundamental, profound, and functional. Fundamental empathy reflects the teacher’s positive interaction and communication using regulated listening skills, being receptive and attentive. Profound empathy reveals teachers’ close interaction and deep relationships with students, they engage in their learners’ individual worlds. This influences learning or academic achievements besides emotional fulfilments and therefore generates honest and positive relationships in the classroom. Finally, functional empathy is the teacher’s skill to combine between the two former kinds of empathy; that is, it is to create good relationships with the whole class and then implementing a sense of respect among the students.

6. The study

The research scheme was delimited by the principles of action research. The aim of the current paper is to describe and analyse some students’ perception towards empathy in relation to their classroom engagement. For this purpose, the current study has been carried out through a qualitative methodology. The main interest was basically to explore the relationship between empathy and interpersonal awareness favourable for learners’ engagement.

6.1. Participants

The target population of the present study included students from the fifth year cohort at l’Ecole Normale Supérieure of Oran. Twenty EFL learners were selected as the sample of the current study, they represented 50 % of the cohort. In fact, the sampling was based on a voluntary basis as students had to submit personal diaries, this necessitated an absolute engagement of the respondents.

In fact, the main reason behind the choice of the target population, i. e., fifth year students was mainly because of the nature of our investigation. First, in terms of the participants maturity, and essentially because they could provide more in-depth data as they had to report about their learning journey at the ENS including the previous years. In addition, the researcher expected candid as she has been their teacher and they were used to discussions and debates during her classes. In other words, she has had developed a sound relationship with them beneficial to have opted for students’ personal reflections as a tool of data collection in which they would provide honest impressions especially related to personal and emotional aspects.

The participants ranged from 22 to 24 years in age. They were 2 boys and 13 girls. In fact, there were simply two boys in the fifth cohort. They all study English for mostly vocational purpose. The training they receive is to be equipped to enter the teaching profession in secondary schools. In effect, their curriculum includes different subjects; namely, Didactics, Educational Psychology, Syllabus Design, Textbook Evaluation, Pedagogical Trends, Applied Linguistics, School Legislation, Literature, Civilisation, Linguistics, Sociolinguistics along with the practical subjects including Grammar, Oral-Expression, Written-Expression, and Reading Techniques.

6.2. Procedure

Participants’ diaries were used as the basic instrument for the current study in order to collect detailed information about the learners’ perceptions towards empathy as well as their personal engagement related to empathic type of teaching. The aim was to provide an insight on the respondents’ experiences along their EFL learning journey. In fact, classroom research including diary studies is claimed to be beneficial to have a deep comprehension of the informants’ actions and reactions, for as Nunan (1992) affirmed “human behaviour cannot be understood without incorporating into the research the subjective perceptions and belief systems of those involved in research.” (p. 54).

Similarly, Crabtree & Miller (1999) claimed that one of the advantages of this approach is the close collaboration between the researcher and the participants while enabling these ones to tell their stories. Through these stories the participants are able to describe their views of reality, conscious and even unconscious thoughts through their subjective reflections of classroom events, and this enables the researcher to better understand the informants’ actions. Consequently, the participants’ diaries of the actual work were considered as a useful tool and at the same time a necessary source of data in the sense that they provided the kind of information that one could not directly observe from the outside. The reflections, then, allowed having more understanding of the students who would convey their particular experiences in their EFL learning using their own words.

In this respect, the twenty participants were explained the aim of the study. They were expected to reflect upon their personal experiences including their involvement and reactions in the EFL classroom, and with different teachers. They were also explained to add any details they judged necessary to the research direction. They were asked to submit their personal diaries along the first semester of the academic year 2020-2021 and were assured by the researcher that the content of their reflections would be kept and treated in a confidential way and that their identities would be kept anonymous along the data collection as well as data analysis, and when using direct quotations from their diaries. Therefore, the two ethical issues that should be considered in any scientific research- consent and confidentiality- have been taken into account in the present investigation.

6.3. Findings and Discussion

In terms of students’ perception towards empathy, all participants acknowledged its importance for their language learning and also for their social classroom integrity. Indeed, the respondents were aware that empathy is considerably favourable to create a safe atmosphere where their engagement could be encouraged. Such an awareness led to an active involvement in the classroom, a positive attitude towards the language learning, a candid consideration for their classmates, and mainly a mutual respect concerning turn taking, one case confessed:

“the classroom is a sonic place where ideas are discussed. It is beneficial to take a while to think, listen to others, and share their thoughts. I’ve decreased my participation being aware of the others’ turn.”

In addition, most respondents related empathy to be one of the teacher’s characteristics; that is, empathic teacher has been focused and often repeated in their personal reflections mainly in decreasing their anxiety and building a better self-esteem. In fact, this self-esteem was most of the time tightly linked to self-efficacy; that is, when they could succeed an assignment because of the teachers encouragement and support. A case affirmed:

“I remember once the teacher asked me to answer, I hesitated but when she knocked her head to push me to say it I could answer and I was pleased to give the right answer especially when the teacher approved with a like with hands.”

In this sense, the kind of feedback the teacher provided seemed to have also an impact on the decision the respondents took whether to take the risk to participate or not in their language classroom. The positive or smooth feedback could be verbal or non-verbal as stated in the previous example. In this respect, some students claimed that before they spoke their voice, they first weighed the teachers’ reactions and the way they responded to their classmates’ replies and opinions.

Moreover, findings revealed that teachers’ empathy had a direct influence on their learners’ attitudes towards participating and interacting in the classroom; the informants confirmed that they would feel free to use the language without the fear of making mistakes or receiving negative feedback when their teachers showed care and understood them in terms of their difficulties and challenges they encountered in their learning process.

Here are some excerpts showing how the presence or absence of empathy could relatively increase or decrease students’ involvement, and also how it could affect their personal affective state:

- “I remember once, when a teacher told me ‘hold your horses’ when I was explaining my exposé’; I got disappointed he didn’t try to understand my enthusiasm towards the point I explained…”

- “Actually, I’M. shy and when it comes to answer my voice starts shaking; so, a smile from my teacher can cheer me up; however a glance can freeze me…”

- “in the beginning entering the oral classroom was a source of anxiety as I knew that I had to speak; in fact, I was afraid the teacher would detect my mistakes and correct me in front of my classmates. Then, I discovered the way she encouraged our speaking and didn’t really focus only on our mistakes…”

- “I am greatly impressed by a teacher who always starts her lecture by asking us how we feel, and detects our tiredness or bad mood. I really like her class and try to hide my tiredness and interact in her session.”

- “I acknowledge that being aware of empathy, I have better relationship with my classmates in the sense that I respect their thoughts even if I disagree with them.”

- “ I feel the classroom as a second home; the teacher calls us with our first names, he shows us how to be understanding as himself is comprehensive and always listening to us.”

In terms of the cited attitudes, we may acknowledge again that teacher’s empathy plays a vital role in the EFL classroom. First, it creates the appropriate climate where all learners can feel the safety to learn, and especially to voice their minds and give their opinions. It also attracts all types of learners with their different types of personality as well as their mixed abilities. Students are then treated equally and fairly; this would promote their involvement and motivation to persevere in their learning. Finally, the EFL classroom would be considered as their second social shelter where they can exchange their points of view, arguments and orientations. Therefore, they would enjoy better their learning journey.

Furthermore, findings revealed that the teacher could encourage an empathic classroom through modelling empathy and generating respectful, supportive, and positive relationships. Understanding each other was the essence of a healthy communication and rapport between the classmates. Respondents claimed that they appreciated when teachers recalled the notions of respect and tolerance during the students’ interferences and their different perceptions.

Indeed, besides the significance of empathy on some personal and emotional factors, socio-cultural aspect has been proven to be influenced by empathic teaching. Actually, when the learner comes to the educational context, he brings with him the habits, attitudes, beliefs that have already been established at him by his society and culture. Classroom interaction is then dependent on the various and different individuals’ perceptions and reactions. As such, with the presence of empathy, the respondents confirmed that the language learning was not simply limited to the internalization of the received input, but also through classroom interaction, topic discussions, and raising their ‘personal anecdotes and experiences’.

Accordingly, the respective influence of the nature of the class coherence was related to various parameters including the extent to which learners engage into the classroom interaction which was in turn affected by the degree of empathy in their learning context. Some learners perceived the classroom interaction as supportive for their learning; and when the teacher was comprehensible and empathetic they could raise questions, ask for clarifications, suggest answers, voice their ideas; in sum, they appreciated the group dynamic and enjoyed working with their peers to enhance their language learning. On the other hand, some respondents claimed that the absence of empathy-whether that of their teacher or classmates- was rather threatening, and limiting the opportunities for their engagement.

Conclusion

Having developed the sense of belongingness within an empathic classroom, students would feel safe to socialize, participate, interact, and then, to progress in their learning process. Accordingly, Sornson (2013) posited that: “programs that build safety, connection, empathy, and positive social skills invariably lead to a classroom environment in which students both learn more and produce better test scores.”

In this respect, Sornson (2013) suggested that the development of an empathetic classroom can be promoted within a combination of different tips; namely, by creating a safe classroom atmosphere where every student can keep face among the other members of the classroom; through predictable routines in order to practice self-regulation skills; by modelling empathic interaction through teaching specific observation skill and listening; using related literature to develop learners’ insight of personal and others’ experiences; and by building the sense of relationships skills to arouse consideration for others.

Modern education approaches teaching as an effective delivery of knowledge as well as an awareness of emotional training. Empathy as a vital element of emotional intelligence can provide a meaningful learning experience in the educational setting. Empathy makes teachers aware of their learners’ needs, challenges; and help them understand their struggles. Besides, this aspect plays a vital role in the establishment of good teacher-learner rapports through an understanding environment.

Empathy is revealed by a metacognitive consciousness about how to deal with the others, and how to manage a suitable interaction and behaviour. Thus, by modelling empathy in the classroom, teachers will provide a psychological and affective support for all students. Teaching with empathy influences positively the learners’ commitment and performance in their learning process, promotes a mutual respect among students, and builds an engaging classroom atmosphere for every single student with different levels and traits. In this sense, empathy should be enhanced at learners to help them lead a successful journey in their academic courses and regulate themselves for their future careers. Serious consideration to empathy- as a cognitive and affective factor- needs to be raised in the teacher’ professional development for a personal self-regulation and to be properly used in the learning/ teaching process.

Teaching with empathy influences greatly the learners’ commitment in their learning as mutual respect is promoted. It builds an engaging classroom atmosphere favourable for close and frequent interaction and provides the most beneficial results for moral modelling, learning outcomes and social exchange.

Finally, given the significance of teacher empathy for comprehensive and dynamic teaching, it is advocated that teacher’s empathy needs to be an integral part of teacher professional development and practice in the EFL classrooms. Respectively, it can be engraved at learners when it is adequately modelled by their teachers, and consequently learners would develop positive attitudes towards their own learning within a welcoming and supportive atmosphere.