Introduction

The significant increase in immigrant and displaced populations around the world over the last decades has led to a surge in immigration-related cinematic productions. This paper aims to offer a conceptual and comparative analysis of films focusing on how aesthetic aspects and storytelling conventions contribute to a greater narrative of displacement. Like any other genre, cinema of the displaced benefits from advancements in production and distribution, allowing filmmakers to respond to cultural, ethnic, and ideological issues while maintaining commercial success. These productions, both fictional and factual, contrast the political discourse marked by anti-immigrant sentiments and the diversity of social experiences following geographical displacement and cultural movement of individuals. In fact, films offer more nuanced perspectives by portraying the displaced of distant worlds, fictionalizing the setting but not the issues they reflect. This paper takes as its starting point the words displacement, refuge, and immigration as key notions referring to a physical movement of persons to relocate due to political situations, armed conflicts, environmental crises, or any other factor.

Contemporary films that portray the social conditions of immigrants create an awareness of the resistant force aligned with political challenges. Narratives such as, We Were Not Born Refugees (2020), This Rain Will Never Stop (2020), Limbo (2020), Capernaum (2018), First They Killed My Father (2017), and Born in Syria (2016) capture the determination of characters relocating to other parts of the world. They follow the forced displacement of individuals towards safety only to find themselves in the face of other violent circumstances. The framework of their movement is understood in terms of reciprocity. The host nation meets the continent-crossing individuals as agents of violence themselves, widening the cultural and ideological gaps between one world and the other, which displacement could have initially bridged. The degree of fictionality in these films varies according to the world’s references pointed at. To a unique degree, it can be suggested that these “films not only contain but are worlds” of virtual nature existing in collective human intentions to invoke imaginative and symbolic responses (Yacavone, 2015, p. 58).

The representation of cinema of the displaced has been explored extensively, discussing how creative engagement with the experience of refugees impacts viewers and their perception of the real. Alain Gomis’ films are representative of twenty-first-century displacement, with characters living alienated resulting in their departure on a quest for identity. This is suggested through multisensorial production, combining sounds and silences to reflect the nonverbal feelings of displaced characters endure (Sendra, 2018). This sentiment is frequently intrinsic to the structure and form of the film, symbolizing the movement. They bring into view the unseen social spaces and political landscapes from which immigrants displace and towards which they emplace (Woolley, 2023). In fantasy, science fiction, and supernatural narratives, story-worlds differ narrowly from what is conceived as real in serious cinema, calling for more focus on the nuances of fantastic films. Both the real and the made worlds, though distant spatially and ontologically, are composed of recognizable elements. Dune (2021) and Avatar: The Way of Water (2022) are two contemporary films set in distant worlds and composed of identifiable sets of referential artifacts representing displacement and relocation (Boillat, 2022).

This paper explores the aesthetic representation of displacement narratives in films focusing on how elements of the constructed worlds are recognizable invariants of the real world. It establishes that Dune (2021) and Avatar: The Way of Water (2022) exemplify social and cultural structures of displacement, relying on Nelson Goodman’s philosophical concepts of worldmaking in art. Goodman argues that worlds in art are made and not found. They are created versions of already existing systems. He asserts that multiple versions can exist and be equally valid, resulting in diverse structures construing the same world. But only the ones that fit together coherently and align with real-world structures can be acceptable. Aligned symbols and references are metaphoric denotations and exemplifications of wider cases. Accordingly, Goodman invites us to “consider, first, versions that are visions, depictions rather than descriptions” (Goodman, 1978, p. 102). In doing so, we see art as a symbol referring to something beyond itself and implying its relation to external realities. So, what aesthetic aspects are films using to indicate the real?

1. Worlds as Symbols

Goodman reconsiders the problematic question “what is art?” that often leads to frustration and confusion, reconceptualizing it to “when is art?” Art functions as a symbol and works of art should be explored as symbolic. While composed with aesthetic significance and intrinsic qualities of an artwork, it is also externally representational. Both properties are inherently connected, making art transient in nature symbolizing different things at different periods of time (Goodman, 1978, p. 69). Consequently, each vision of an artwork is a version of the world that contributes to its symbolic function. The fictional worlds that Dune and Avatar (instead of Avatar: The Way of Water) created are fantastic places with their own systems focusing their attention on political, societal, and ecological issues. The films project visions of the world that combine harsh political realities with a need to relocate to other unfamiliar territories. While they explore the moral questions that trigger displacement, they highlight the implications of resettlement for the displaced individuals.

The world-centered narratives known to science fiction and fantasy engage in introspective narratives. They create new states of the world with speculative dimensions, often involving metaphorical adjustments. The other worlds become sub-creations, a notion in worldbuilding introduced by J. R. R. Tolkien, with internal consistency similar to the primary world. In fact, “the laws governing our world serve as a point of reference for understanding those of the other world” (Boillat, 2022, p. 57). Dune and Avatar are evolutionary narratives that each combine two worlds bridged by a movement from one and a movement towards the other. Marie-Laure Ryan suggests receiving this type of fiction as an intertext because it incorporates referential knowledge that responds to factual experiences. Considering world-films intertextually acknowledges the existence of another from which meaning is drawn (Ryan, 1991). Accordingly, references in fiction are factual and related to empirical reality. “This general view involves the adoption of what may be identified as the world variance conception of the meaning and truth status of the representational elements of works of (artistic) fiction” (Yacavone, 2015, p. 25). Dune and Avatar conceptualize variations of the primary world, attributing meaning and truth to characters, events, places, and objects. These narrative components are significant representational elements of the film. They constitute the pillars that render the artwork a symbol itself.

Dune and Avatar are contained within a cinematic landscape of displacement as aesthetic wholes in nature. James Cameron celebrated the emerging visual effects by integrating them as intrinsic to the narrative and the film’s dynamics. Jack Sully, the protagonist Na’vi in Avatar, is the chief of the Omaticaya clan. His appearance is singular as he chose to remain in his Na’vi avatar in the film’s prequel, metamorphosing into one of the most heroic inhabitants of the planet Pandora, the Toruk Makto of his time. The morphing extends to Avatar (2022) as visual imagery, adding details of related value to constitute scenes of the life of the Na’vi chief and his family. The accumulated shots and sounds of family scenes are an integral part of a story-world that transcends Pandora. Even though bounded by the physical borders of the screen, representational narrative elements extend beyond the experiential boundaries of cinema. Scenes portraying Jack sharing precious memories, family moments, and parenthood concerns are constituents of the viewer’s world. Goodman proposes that “right world-descriptions and world-depictions and world-perceptions, the ways-the-world-is, or just versions, can be treated as our worlds” (Goodman, 1978, p. 4).

2. Indexical Signs of Displacement

The ontological link between objects and referents is of indexical nature. Narrative, visual, and auditory elements capture and represent aspects of reality. Through symbolic exemplification and conventional cinematography, concrete associations between the film-world and the real world are made, fostering a sense of referential recognition for the audience. Avatar relies on multiple compositions in framing a sense of displacement. Leading line composition is often associated with relocating characters in the film. When the Sullys initiate their journey, they are met with a horizontal leading line (figure 1). While typically this line direction suggests stability and balance, in a displacement narrative, it conveys a sense of instability and disorientation as it is contrasted with a subtext emphasizing the need to find safety. In fact, Jack is aware of the implications of his decision to relocate. He redirects the movement of his family diagonally (figure 2), confirming the dynamic nature of his uncertain exploration and with it his responsibility to protect them even at the expense of a comfortable familiar life. At their arrival at the Metkayina Village (figure 3), the Sullys cross the horizontal line, creating a sense of disruption and unease associated with displacement. It is a visual metaphor for the upheavals and lack of groundings characters will be experiencing in this new land. This is also symbolic of the framework understood in terms of reciprocity. The Metkayina clan meets the line-crossing Na’vis with a degree of hostility at first. They fear war would follow the movement of refuge-seeking Jack, who is seen as an agent of violence.

Figure : Displacement Initiated

Source: Cameron, 2022, 48:51

Figure : Diagonal Redirection

Source: Cameron, 2022, 48:54

Figure : Arrival and Crossing

Source: Cameron, 2022, 49:48

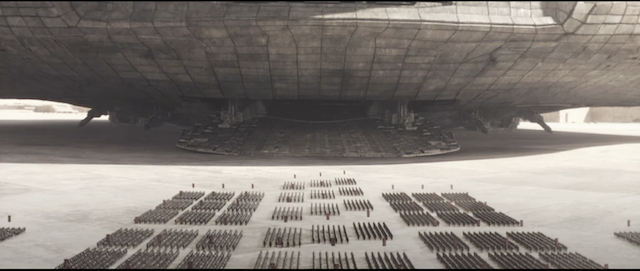

Similarly, Dune bears witness to depictions and perceptions that intentionally describe realities occurring both internally and externally. As in Avatar, leading lines are symbolic and expressive of movement. An early scene in the film (figure 4) depicts the arrival of the "Herald of the Change" with members of the imperial court to inform the House of Atreides that the Emperor commands them to take control of Arrakis, involving displacement. Prior to that, the Harkonnens army leaving Arrakis (figure 5) is seen harmoniously arranged to equally fill the screen. The frame displays a number of characters that seem to exceed previous ones, exemplifying the increased number of individuals relocating from one space to another. Although the lines are diagonal and dynamic, implying motion, they also intensify a sense of anxiety, reflecting discomfort and restraining spaces. At their arrival on the unfamiliar planet (figure 6), Paul Atreides and his mother Lady Jessica’s movement towards a transportation vehicle after they had reached Arrakis is symbolic of their journey. They arrived from their home planet Caladan, but their movement will continue as direct lines lead them towards another aircraft removed from the frame. The scene evokes a feeling of continued displacement and unsettlement as displaced individuals reach temporary rather than final destinations, ones they could hardly call home.

Figure : "Herald of Change"

Source: Villeneuve, 2021, 07:29

Figure : Armies Relocating

Source: Villeneuve, 2021, 02:53

Figure : Paul Atreides and Lady Jessica

Source: Villeneuve, 2021, 36:39

The leading line composition in Dune and Avatar is indexical and exemplifies visual motion as it guides the viewers' experience through characters’ journeys. Lines draw the paths of explorations, often adding depth to the scenes that lead the eyes to a limitless point of focus: an unknown destination within the frame itself. Diagonal lines dominate the composition, conveying a sense of tension, imbalance, and decreasing stability. Characters’ departure from the norms by following the narrowing path represents change and disruption. Accordingly, the film aesthetically structures displacement to exemplify experienced realities. It is intrinsically expressive of what it is and externally of what it symbolizes. Individuals who are uprooted from their homes and forced to relocate to uncharted territories are met with challenging social, cultural, and personal upheavals. In both the film-world and the real one, the displaced grapple with the need to assimilate into a new social environment while preserving their heritage. The next sections illustrate how cinematic techniques reveal a sense of discomfort and disjunction that challenges the emplacement of displaced individuals.

3. Sounds as an Aesthetic Mode of Displacement

Auditory elements are symbolically constructed within the world of the film, playing a crucial role in shaping external experiences and influencing emotions. Scores in films are usually non-diegetic and heard only by the audience, but in Dune’s story-world, scores are partly the sounds of its nature. Characters are aware of their existence as an integral part of their internal reality, creating a direct link between them and viewers. They constitute the auditory link that aesthetically connects the secondary world of the narrative to its primary one. A key narrative moment in the film is its opening frame. It opens with the line “dreams are messages from the deep” accompanied by a black screen and an incomprehensible electronic-like sound. It sets the tone for the narrative, establishing a connection between voices and dreams to understand the distant world of Dune. So not only does it offer insights into the overarching atmosphere of the film, but it also indicates the necessity to explore characters’ dreams and inner voices. Such openings position the viewer “to enter the fictional world on offer. The function of openings is to guide habits of interpretation by beginning the process of familiarization with the fictional world we are entering” (Geraghty, 2015, p. 240). So, viewers first experience a meaningless voiced sound that could be symbolic of unspoken languages by the displaced. The accompanying line, “dreams are messages from the deep”, seems to translate what the voice might have spoken in an unfamiliar tongue. Not only that, but also initiating a journey into the unknown realm of dreams.

Sounds in Dune are also composed to create a sense of discontinuity. Paul’s failure to powerfully use his voice in the beginning of the film creates a sound-image disjunction. When he commands his mother to give him the glass of water, the voice is heard only after his lips stop moving. The components of the scene are intentionally misaligned to convey emotional tension. Paul’s internal conflict and struggle to use his commanding voice can engage viewers with his own subjective experience. This metaphoric scene symbolizes the discomfort in misaligning intention and action, introducing discord between what is occurring and what is real. The unpredictability of voices and their delay exemplify the circumstantiality of displacement, highlighting the unfamiliarity with new places displaced individuals feel, making them base their decisions on situational circumstances. Additionally, the disjunction between images and sounds builds suspense and uncertainty, leaving viewers emotionally disturbed. The unrest that is internal to the film-world expands beyond the temporal experiences of audiences as delayed voices indicate a manipulation in temporal reality. They increase a feeling of being out-of-sync, reflecting the disorienting experience of displacement, reinforcing a sense of isolation.

Lo’ak experiences, in an aesthetically more subtle way, a similar sense of isolation in Avatar. The absence of verbal communication with the Tulkun he meets in the Three Brother Rocks scene confirms a sense of alienation because of his displacement. The sequence juxtaposes their differences to accentuate a shared disjunction with their new environment. Expressionistic sounds are arranged in the following scenes to intensify the emotional suggestions, exaggerating them with aerial shots. The soundscapes of the scene are juxtaposed with the immensity of the Tulkun, creating heightened reality followed by tension. The Tulkun’s point of view (POV) shots convey the cultural contrast between the two contrasted subjects. Textures also differ depending on whose view is shared with the audience, shifting from cold to warm hues. On the one hand, the contrast of colors shows a warm Lo’ak, signifying a friendly unhostile individual. He is not an agent of violence and should not be met with a reciprocity of violence. On the other hand, the two primary texture hues in the scene, orange and blue, are complementary colors indicating both Tulkun and Lo’ak share a similar experience of alienation. By contrasting the displaced characters’ perspectives through sounds, coloring, and other sensory and visual elements, film-worlds emphasize the challenging sense of isolation associated with relocating.

4. Frames of displacement

Figure : Close-up on Paul Practicing the Voice

Source: Villeneuve, 2021, 04:55

Close-up shots are visual motifs that place viewers closer to characters’ subjectivity. Unlike POV shots, close-ups establish visions rather than share a character’s actual perception of the film-world’s elements. In Dune, close-ups provide long, magnified views of Paul. In such frames, he is isolated from the world of the narrative and brought closer to the world of the viewer, asserting an aesthetic sense of displacement. The dramatic association of Paul’s sense of isolation and close-ups directs the viewers’ attention to immediately identify with his thoughts and feelings. The audience witnesses the burden associated with an isolating individual journey. In fact, whenever a close shot is sustained, Paul is shown to either be thinking, having a vision, or remembering a dream. In the film, close-ups, with focus on facial expressions, are predominantly used to convey Paul’s personal experiences and inner power (figure 7). So, access to his mind reveals an introspective consideration of his reality. The expressive eyes of Timothée Chalamet, the actor playing Paul, provide insights into the character's fear of the future and internal struggle to understand it. The subtle change in his facial demeanor captures the challenges and upheavals Paul grapples with.

Figure : Close-up on Paul's Teary Eyes

Source: Villeneuve, 2021, 01 :38 :15

Outside Arrakis, close-ups isolate Paul visually to aesthetically align with the theme of displacement. He experiences a sense of alienation in the new unfamiliar desert he relocates to. Although he willingly explores Caladan knowledge and Fremen culture, he struggles to adapt to the hostile desert. Timothée Chalamet’s facial expressions capture tension in the close-ups to contribute to the sentiment of uncertainty about his future (figure 8). He conveys doubt and fear through subtle twitches, tightening jaw, furrowed brows, and narrowed (teary) eyes. At times, the camera captures his intense gazes or rapid eye movement to express his uneasiness with other characters, places, or events. The layering of emotions in the different shots emphasizes the instability of Paul’s situation contrasting the tension portrayed in the close-ups with visions and long silences. His visions amplify the sense of disorientation often coupled with uncertainty. His contemplative silences in such shots contribute to the visual intensity of each frame and assert the overall unsettling sentiment of displacement. Close-ups are Paul’s moments of internal realizations and the viewers’ moments of external confrontation with the unrest displaced individuals experience.

Figure : Close-up on Jake's Hand with a Rope Tied Around it

Source: Cameron, 2022, 01:03:58

In Avatar, close-ups are significantly used to depict tension and characters’ resilience to assimilate the way of water. After the arrival of the Sullys to the Metkayina clan, a close-up shows Jake tightly securing a rope around his wrist and hand when learning to ride the Tsurak (figure 9). The rope is a synecdoche used to refer to the whole of the situation of displacement. Partly, it symbolizes the constraints imposed on displaced individuals while they try to assimilate the culture of the host nation. Jake’s determination to become a Na’vi of the waters was met with a restriction of freedom and autonomy. Such limitations are measures implemented by nations in countries around the world to manage the newly arriving populations. Although policies encourage cultural assimilations, they impose restrictions on specific employment opportunities, social benefits, and cultural practices out of national security concerns and perhaps political considerations. The scene, in a more positive sense, depicts Jake’s willingness to integrate the new environment. He navigates the challenging upheavals of the new and unfamiliar life by bonding with Tonowari through a shared riding experience. He and his family collectively work towards assimilating the new culture after their placement within the Metkayinas, lessening the sense of displacement. But while close-ups show the characters’ feelings and reactions to the culture, they fail to portray their place in the new uncharted environment of displacement. The Sullys are frequently framed while exploring unknown territories entirely and in relation to their spatial environment. Shots are taken from higher angles, capturing a broader view of the surroundings. These are, in fact, establishing shots. Typically, they identify and introduce new locations, providing informational frames about the overall atmosphere of the following sequences. However, in Avatar, establishing shots serve yet another purpose. The camera movement is never fixed, using tracking and trucking shots to follow the journey of the characters (figures 10 and 11).

Figure : Establishing Aerial Shot 1

Source: Cameron, 2022, 49:40

Figure : Establishing Aerial Shot 2

Source: Cameron, 2022, 50:33

The non-static motion conveys the inherent unsettling nature of displacement. When contrasted with darker hues (figures 12), it expresses a sense of discomfort. The continuous high-angle establishing shots in this narrative sequence imply the vulnerability of the family that is uprooted from one space and thrown into vast unwelcoming others. They are shown smaller and weaker to emphasize the massiveness of the unknown world and its foreignness. So, elevated establishing shots reinforce a feeling of helplessness, highlight the vulnerable status of the displaced, and symbolize the magnitude of the sense of loss to viewers.

Figure : Establishing Aerial Shot Contrasted with a Darker Hue

Source: Cameron, 2022, 49:25

Conclusion

Through aesthetic exemplification, filmmakers position their productions in a consciously ethical representation of a world dilemma, committing to reflectively portray how individual identities experience displacement. Their productions highlight the significance of cinema as a reflexive symbol of cultural and social structures. Cinematic techniques metaphorically and aesthetically symbolize primary world structures through secondary world ones. They are equally insightful in portraying the introspective realities of the displaced, who, in the face of cultural shifts, remain resilient. In understanding the different filmic practices, we unravel the interconnectedness of art and its context. Both films dynamically confine inside and outside the screen, prompting audiences to reflect on the represented human condition with its triumphs and struggles. Accordingly, by navigating the symbolic imagery exemplifying the circumstantial and temporal context, viewers embark on a shared journey along with the displaced characters. Although the examined films might not be openly about displacement, the reflections they offer on such topic shift perceptions to a complex narrative in the story-worlds. Avatar and Dune build film-worlds at the boundaries of reality. They polyphonically double the sense of discomfort and displacement, inviting us to distant futures and planets much like ours. Viewers of the films do not shift from secondary to primary worlds, or from future to present, they experience interwoven realities that unfold concurrently. Goodman’s question “when is art?” invites us to reconsider the two films as a response to a global cultural context exploring the pressing issue of displacement creatively. Aesthetic expressions align us with characters’ perspectives to understand their sense of loss, disjunction, and uncertainty. So, positioning displacement in a distant film-world closer to us by its medium of delivery and aesthetic choices surmounts systematic modes of thought. In fact, such films assert that reconstructing reality is a necessary response to ongoing crises. From innovative scores to image-sound disjunction, cinematic techniques and motifs evolve to expressively fit the needs of the context they respond to.