Introduction

The topic of academic guidance is one of the most complex issues facing those responsible for the education system in Algeria. It is considered a human process involving a range of services provided to students by educational guidance counselors. The purpose is to help students understand themselves and their problems, enabling them to resolve these issues. Additionally, guidance aims to assist them in choosing a study specialization based on their personal characteristics, preferences, and readiness, ensuring success and academic achievement.

This period coincides with adolescence, which is considered a phase where individual capabilities and inclinations emerge. Therefore, guidance can direct them towards the type of education that aligns with their desires and abilities. However, the guidance process often faces the complexity of external factors that hinder the realization of the student’s educational aspirations.

One of the most significant factors is the family, which is considered the strongest representative of culture and the most influential group in shaping an individual’s behavior and futures orientations. Since the student grows up in a family, which is the primary environment where they learn lifestyle patterns and acquire various prevailing standards and behaviors, the family holds a powerful influence over the individual’s behavior, futures orientations, and psychological and social adaptation.

Based on the parents’ attitudes, their personal views, and their evaluation of various academic specializations, the student may find themselves grappling with the challenge of choosing the type of study under the influence of parental desires. Taking into account the parents’ preferences for different academic branches and their categorization of certain academic specializations, some parents impose their personal inclinations on their children. These considerations are specific to them, leading the student to bear the burden of their parents’ ambitions, forcing them to pursue a specialization that does not align with their inclinations and may not even match their abilities. It is evident that some parents seek to fulfill their own hopes and personal aspirations through their children.

This may be attributed, according to Al-Shahimi, Mohamed Ayoub, to the belief held by some parents that certain specializations are limited to specific social classes, while others are considered almost forbidden or unfamiliar to other social classes (Al-Shahimi, 1994). Additionally, social trends contribute to the preference for certain scientific fields, such as the sciences, over humanities and social sciences. These values restrict parents’ attitudes toward their children’s futures. In this context, several studies have highlighted one of the significant problems facing adolescents: the frequent interference of parents in their academic affairs, either out of concern for their academic future or indirectly seeking to fulfill their aspirations.

In this regard, studies, such as the research by Ahmed Zaki Mohamed, have shown that a considerable percentage of the sample (528 individuals) indicated that their mothers do not allow them to study the subjects they desire, with 33 % of boys and 56 % of girls stating this. Additionally, 4 % of boys and 13 % of girls mentioned that their mothers encourage them to outperform their peers at school (Mohamed, 1954).

Naturally, such parental behavior, as perceived by the children, will impact their academic achievement and consequently guide them towards different academic branches. There are unconscious motives that lead some parents to compel their children to pursue a specific academic specialization, directing them towards a field that does not align with their desires and abilities on the one hand, and the requirements of the specialization on the other. This type of imposition only results in harm to the student, affecting their academic and professional future.

This problem is prevalent in many societies, but Algerian society has its own characteristics and features. In light of the above, the current research aims to uncover the extent of the impact of parental desires on academic guidance. Does parental desire influence academic guidance for students in the first year of high school?

1. Research Methodology and Study Framework

1.1.Study Hypothesis

This study examines how parental desire shapes and influences the educational orientation of pupils entering their first year of lycée. The transition to high school represents a critical phase in a student’s academic journey, as it is often the period when students are required to make significant decisions about their future educational and professional paths. While students’ aptitudes and interests are essential factors in these decisions, a growing body of research suggests that parental influence is crucial in guiding or even determining the choices made during this pivotal time. Parents’ aspirations, values, and expectations can directly or indirectly affect the courses or fields of study their children pursue. This paper aims to explore the mechanisms through which parental desires manifest in the decision-making process, and how these influences align or clash with the students’ personal ambitions and academic capabilities. By investigating these dynamics, the study sheds light on the broader social and cultural forces at play in shaping educational outcomes and offers insights into the long-term impact of such influences on students’ academic and professional trajectories.

1.2. Study Curriculum

Curricula in scientific research are defined as “the method by which a researcher studies the problem in question” (Turkish, 1984, p. 107). Given the nature of this study, which seeks to explore the influence of parental desire on the academic guidance of first-year high school students, the descriptive research method has been selected as the most appropriate approach. The descriptive method is particularly well-suited for educational research because it allows the researcher to observe, analyze, and describe the phenomena as they exist naturally without manipulating the study environment. In this case, the focus is on understanding how external influences, such as parental expectations, manifest in students’ academic choices and whether these influences align with or diverge from the students’ aspirations.

By employing a descriptive approach, this research aims to systematically document the current state of parental involvement in academic guidance and the extent to which this involvement may shape or limit students’ academic trajectories. This method is ideal for identifying patterns, relationships, and trends in parental influence, making it more appropriate than experimental or correlational approaches, which might not capture the full complexity of the social and psychological factors at play. Moreover, the descriptive curriculum will provide rich, qualitative insights that can help illuminate the nuanced ways in which parental desire impacts students’ decisions, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of this educational challenge.

1.3. Research Sample

The research sample consists of 122 male and female students in the first year of high school, enrolled across all common educational branches, as illustrated in Table and Figure (01). The selection of this sample was carried out randomly to ensure that the data collected reflects a broad and unbiased perspective of the student population in this educational stage. The randomness of the sample is crucial to the study’s validity, as it minimizes selection bias and ensures the representativeness of the findings.

The following criteria were applied in selecting the sample:

-

Age: The sample includes students aged between 15 and 16 years. This age range is significant because it marks a period of transition in students’ academic lives, where they are required to make important decisions about their future educational and professional paths. At this stage, students are beginning to explore different academic specializations, and they may be particularly susceptible to external influences, such as parental expectations.

-

Gender: The sample was not stratified by gender, as the academic guidance process does not typically differentiate between males and females in the context of the research. By including both male and female students, the study aims to capture a holistic view of parental influence, while recognizing that parental desires may manifest differently across genders. However, the study assumes that the fundamental mechanisms of parental influence are not inherently gender-specific, justifying the mixed-gender sample.

-

Educational level: The sample consists exclusively of first-year high school students, representing a uniform educational level across various branches of study. Focusing on this specific group allows the research to target a critical point in students’ academic trajectories, where they begin to receive formal guidance on subject specialization. The common educational level ensures that the sample is homogeneous in terms of academic experience, making it easier to isolate the variable of parental influence.

By adhering to these criteria, the sample is well-suited to provide insights into how parental desires may influence academic guidance at a crucial decision-making juncture. The random selection process and the diversity of the sample in terms of age, gender, and educational pathways contribute to the reliability and generalizability of the study’s results.

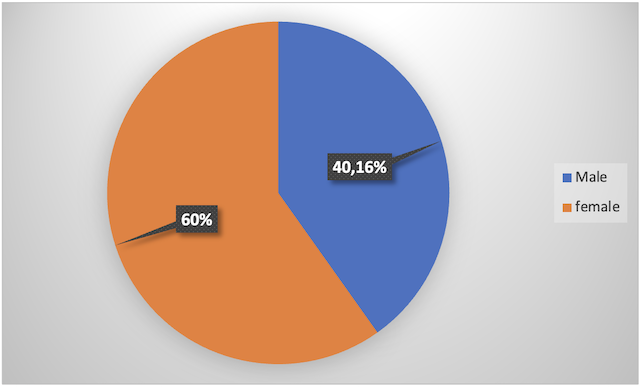

Table No. (01) : Illustrates the distribution of the study sample by gender

|

sex |

repetitions |

Percentage |

|

Male |

49 |

40.16% |

|

female |

73 |

59.83% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

Figure No (01): Illustrates the distribution of study sample individuals according to sex.

It is evident from Table No (01) that the percentage of females in the study is 59.83%, while the percentage of males is 40.16%. This discrepancy in gender distribution may reflect broader trends in educational participation or societal factors that influence the enrollment of male and female students at this stage of their academic journey. Although the sample was not stratified by gender, this higher representation of female students could suggest that girls, at this stage of high school, are either more numerous in the general population or more engaged in academic processes, such as course selection and academic guidance. This difference may also provide an opportunity to explore whether parental influence manifests differently depending on the gender of the student, even though the study initially assumes that the guidance process does not inherently distinguish between males and females.

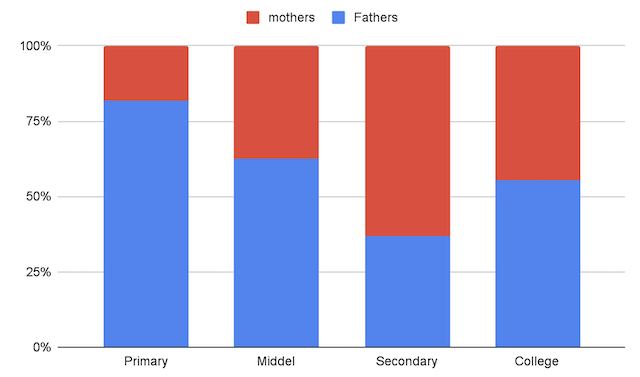

Table No (02): Shows the educational level of the parents

|

Level of education |

fathers |

Mothers |

||

|

repetitions |

percentage |

repetitions |

percentage |

|

|

Primary |

09 |

07.37 % |

02 |

01.63 % |

|

Middel |

58 |

47.54 % |

35 |

28.68 % |

|

Secondary |

35 |

25.40 % |

60 |

49.18 % |

|

College |

20 |

16.39 % |

25 |

20.49 % |

|

Total |

122 |

100 % |

122 |

100 % |

Figure No (02): Illustrates the educational level of the parents

Through Table and Figure No. (03), it is evident that the percentage of parents with only an elementary education is relatively small, ranging from 1.63 % to 7.37 %. This low percentage suggests that few parents in the sample have limited formal education. In contrast, the percentage of parents with a university education is noticeably higher, at 16.39 % for fathers and 20.49 % for mothers, indicating a significant presence of higher education among the parental population. However, the data reveals that the majority of parents have an educational level in the intermediate and secondary range, forming the largest group. This distribution reflects a predominance of parents with moderate educational backgrounds, which could play a crucial role in shaping their expectations and involvement in their children’s academic guidance. It also suggests that the influence of parental education on students’ choices may be nuanced, as parents with higher educational attainment might have different aspirations for their children compared to those with lower educational levels.

1.4. Research Instrument

The research instrument employed in this study consists of a comprehensive questionnaire containing 25 items. These items are designed to capture both quantitative and qualitative data, thereby providing a well-rounded understanding of the research problem. The questionnaire includes closed-ended questions, requiring simple “Yes” or “No” responses, which facilitate the collection of clear, categorical data. Additionally, open-ended questions are included, allowing respondents to express their opinions and experiences freely. These open-ended responses offer valuable qualitative insights into the nuanced ways parental desires may influence academic guidance, enabling a deeper exploration of the subject matter.

The questionnaire is divided into three key sections:

-

Section I : Personal Information

This section gathers basic demographic data such as age, gender, and educational background of the students. This information is essential for contextualizing the respondents’ answers and identifying any potential patterns or correlations based on demographic factors. -

Section II : Items Related to Parental Desires

In this section, questions focus on the role of parental expectations, aspirations, and involvement in the students’ academic lives. The aim is to gauge how much influence parents exert on their children’s academic decisions, whether through direct guidance, implicit expectations, or external pressures. Closed-ended questions help quantify the prevalence of such influences, while open-ended questions allow for more detailed accounts of parental involvement. -

Section III : Items Related to Academic Guidance

This section explores the guidance students receive regarding their academic paths. Questions probe the nature of the advice and support students receive from various sources (e.g., parents, teachers, counselors) and how these factors shape their academic decisions. The section also examines the students’ perceptions of whether their academic choices align with their own aspirations or are influenced by external factors, particularly parental desires.

After the questionnaires were administered, the responses were collected, processed, and tabulated systematically. The closed-ended questions were analyzed using frequency and percentage calculations, which allow for a clear quantitative representation of the data. Open-ended responses were categorized thematically to identify recurring patterns and insights into the ways parental desires influence academic guidance. The combination of quantitative and qualitative data ensures a comprehensive analysis, making the results both statistically robust and rich in personal perspectives.

2. Presentation and Discussion of Results

To test the validity of the hypothesis underlying the current research, which suggests an impact of family desires on academic guidance for first-year high school students, the results were analyzed and discussed.

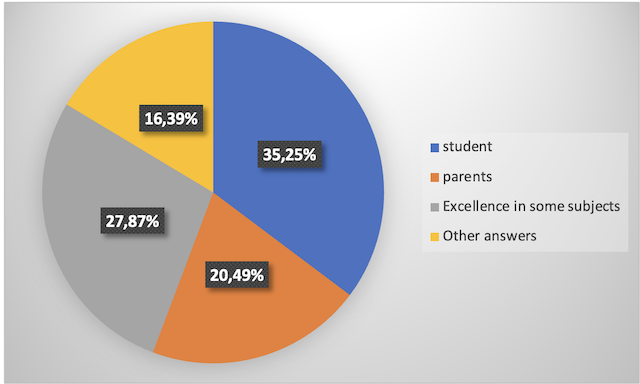

Table No. (03): Shows how the students were guided

|

Repetitions |

percentage |

|

|

student |

43 |

35.24 % |

|

parents |

25 |

20.49 % |

|

Excellence in some subjects |

34 |

27.86 % |

|

Other answers |

20 |

16.39 % |

|

Total |

122 |

100 % |

Figure No. (03): Shows how the students were guided

From Table and Figure No. (03), 35.24 % of students believe they were guided according to their preferences, while 20.49 % think they were guided based on their parents’ desires. Additionally, 34 % of students believe they were guided based on their performance in specific subjects, as required by the chosen common trunk. Therefore, it can be said that guidance in this case took into account the students’ capabilities and potential.

On the other hand, 16.39 % of students provided different answers, indicating that guidance was based on the school’s resources. This suggests that the students’ abilities did not align with their preferences, and in such cases, the guidance counselor intervenes, directing the student based on the available educational seats in the prospective institution.

This satisfaction with guidance among students may be attributed to a form of alignment between the students’ profiles, meaning harmony between their preferences and their academic performance (capabilities), both in core subjects required by the specialization and their overall GPA for progression.

It is worth noting that the parents’ desires did not directly and prominently manifest, but rather indirectly, even among students who believe they were guided according to their preferences. Nevertheless, parents continue to exert an indirect influence on their children through social upbringing, which begins in preschool. During this time, children become accustomed to hearing their parents’ opinions. This is echoed by Soleimane Madhar, who states:

“This influence takes the form of advice: ’If you do this, it would be better...’. Even if the educational level of the parents is low, they still care about their children’s education. This, if anything, indicates that parents are conscious of the value of knowledge and education, especially considering the political, economic, and technological transformations occurring in the world. It explains parents’ keenness about their children’s future.”

In a study conducted by Origlia on the influence of the family, it was found that there is a match between parents and children in 39.8 % of cases, while opposition was observed in 24.2 %. Parents who allowed their children the freedom to choose accounted for 26.5 %, and parents without any influence were estimated at 7.8 % (Origlia, 1980).

However, a study by Jean Rousselet revealed that 50 % of lawyers, doctors, and industrialists wish to see their children follow in their footsteps. In contrast, 30 % of craftsmen share the same desire. Meanwhile, a significant majority of workers prefer their children to pursue different professions (Rousselet, 1961). In a similar context, a study by Malik Suleiman Makhoul on measuring students’ attitudes toward studying showed that the cultural and economic conditions of parents were related to their children’s choice of future careers. The research demonstrated a positive correlation between seeking parental advice when choosing a future profession and having high or moderate cultural levels among parents.

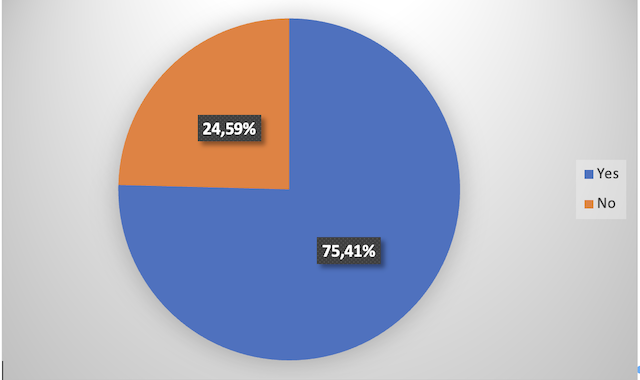

Table No. (04): Illustrates the extent of student satisfaction with guidance

|

Repetitions |

Percentage |

|

|

Yes |

92 |

75.41% |

|

No |

30 |

24.59% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

Figure No. (04) illustrates the extent of the student’s satisfaction with guidance.

The table and Figure No. (04) indicate that 75.41 % of students are satisfied with the guidance they received, considering their direction for the first year of high school as appropriate. They were guided based on their excellence in specific subjects and according to their preferences.

Ahmed Zaki Saleh (1959) conducted a study on students’ academic inclinations and the resulting problems. The study involved a sample of secondary school students and concluded that 72 % of female students and 58 % of male students do not pursue their academic inclinations when choosing the type of education that suits them. This has led to various academic and personal problems, resulting in struggles with career choice and mistakes in selecting a scientific branch after the first year of secondary school (Ahmed Zaki Saleh, 1959).

Therefore, inclinations are considered one of the most important elements in the proper guidance process. Failing to pay attention to students’ inclinations when choosing the type of education exposes them to academic difficulties. However, the intervention of a guidance counselor can eliminate or reduce these problems by guiding students from the preparatory stage to secondary school, where various common branches suitable for the student’s profile are available.

Table No. (05):Indicates the extent of parents’ interest in specific academic subjects over others

|

Repetitions |

Percentage |

|

|

Yes |

26 |

21.31% |

|

No |

96 |

78.68% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

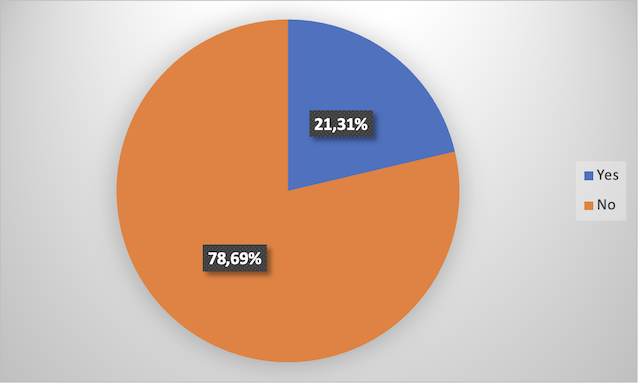

Figure No. (05): Indicates the extent of parents’ interest in specific academic subjects over others

Through Table No. (05) and Figure No. (05), it becomes evident that 78.68% of students are allowed by their parents to study all academic subjects. This may be attributed to their low educational level, which makes them unable to provide suitable guidance and directions that serve their children. Their educational background might not qualify them to understand the guidance process, its requirements for each stream, and the capabilities needed for success. Alternatively, parents may have become aware that imposing a specific type of education for their children is a proven failed approach. As Mohamed Abd El Samed mentioned,

“parents should first be aware that the pressure in choosing their children’s path is a failed approach that destroys their aspirations and disappoints them by ignoring their actual preparations and intellectual abilities. Natural inclinations and predispositions must have a decisive say in choosing the field of study...” (Abd El Samed, 1998, p. 133).

Abd El Rahmane Aissaoui’s study showed that “parents who pressure their children into choosing a specific profession do so out of a desire for compensation…” (Aissaoui, 1992). Mohamed Ayoub Al-Shahimi (1997) emphasizes the existence of some families that impose a certain direction on their children, which may not align with the inclinations of these children. Some of them may abandon a specialization in medicine or a high-paying job to study arts or work in the field of music because they are inclined towards it (Al-chahimi, 1997, p. 213).

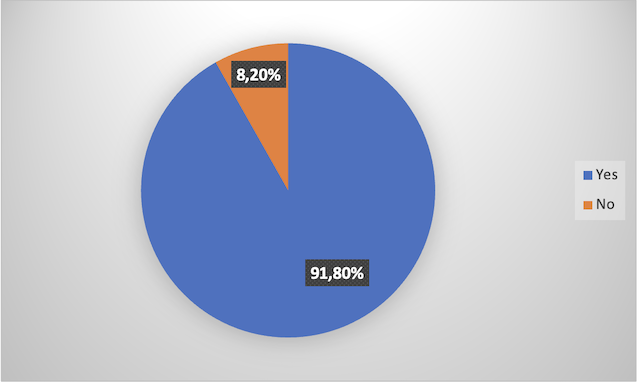

Table No. (06) illustrates the extent to which parents attempt to provide support.

|

Repetitions |

Percentage |

|

|

yes |

10 |

08.20% |

|

No |

112 |

91.80% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

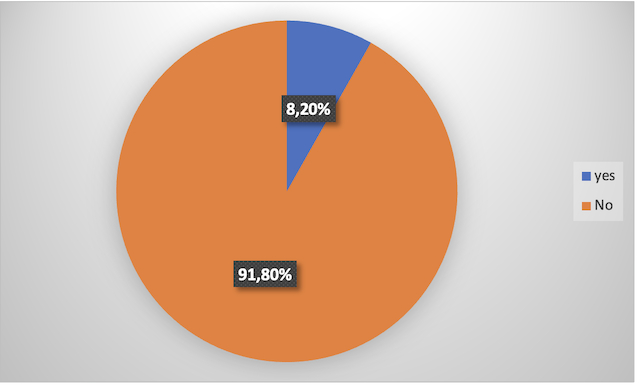

Figure No. (06): Shows us the extent of parents’ attempts to provide support

It is evident from Table and Figure No. (06) that 91.80% of the students’ parents did not contest the choice of the academic track in which their children were enrolled. This could be attributed to their satisfaction with this guidance or possibly to the parents’ confidence in the school, considering the lower educational level, as indicated in Table and Figure No. (02), and the presence of educational guidance counselors in educational institutions, on the other hand.

The study’s findings align with those of EL Arbi Bakhti regarding the importance of family guidance. Assisting parents in helping their children choose the appropriate academic specialization based on their desires, preparedness, and academic and physical capabilities becomes a necessary matter (Bakhti, 1986).

Table No. (07) illustrates the extent of the students’ awareness of the existence of a guidance counselor in middle school

|

Students’ awareness |

Repetitions |

Percentage |

|

Yes |

114 |

93.44% |

|

No |

08 |

06.56% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

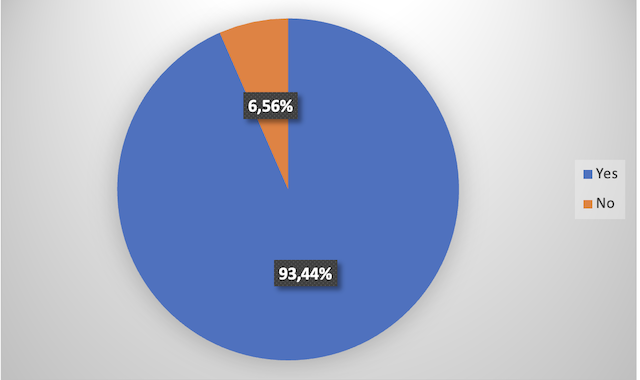

Figure No. (07): The extent of the students’ awareness of the presence of the guidance counselor in the middle school.

It is evident from Table and Figure No. (07) that 93.44% of the students are aware of the presence of the guidance counselor in the institution where they were, indicating that they received appropriate information, guidance, and counseling for the guidance process. This observation is supported by the researcher’s personal experience in the field, as well as the opinions of some school and even vocational guidance counselors who pursued their studies (Master’s degree) in the Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences.

The inclusion of this item was based on the researcher’s field experience, and feedback from some guidance counselors who expressed concerns that their tasks were becoming less focused on the psychological aspects of students. Some counselors mentioned that their duties were increasingly centered around paperwork, files, forms, and records. Some counselors found it challenging to visit classrooms, address students’ issues, and understand their concerns due to time constraints. However, there are counselors who maintain a professional conscience and engage with students, balancing information, guidance, and counseling comprehensively.

The definition of school guidance by Kamel EL Desouki reinforces the idea that guidance is an educational task aimed at guiding students in educational branches based on their abilities and preferences. He emphasizes that counselors and psychological specialists have the duty to carry out this task effectively (EL Desouki, 1990).

Table No. (08): The extent of parents’ encouragement for their children’s education

|

Repetitions |

percentage |

|

|

Yes |

110 |

90.16% |

|

No |

12 |

09.84% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

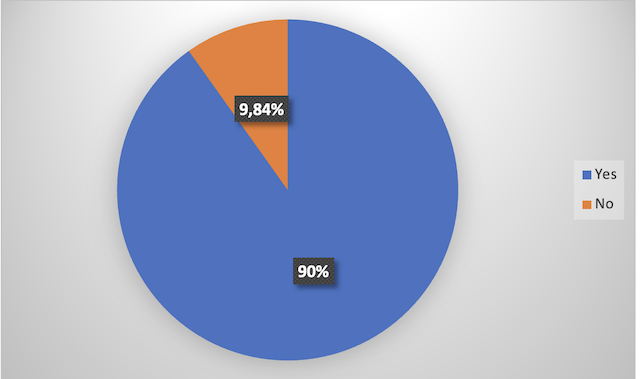

Figure No. (08): The extent of parents’ encouragement for their children’s education

Through Table and Figure No. (08), it becomes clear that 90.16% of students feel that they receive encouragement from their parents for education. This indicates that most parents in our time care about their children’s education and encourage them, despite the low academic levels of some, as shown in Table and Figure No. (02). This, if anything, reflects the awareness of parents of the value of knowledge and academic success.

In this context, a study by Morrow. W and Wilson. R (1961) found that learners who achieve high grades describe their parents as accepting, trusting, compassionate, and not harsh, more than learners with lower results (Abd El khalek, 1982). This is supported by the study of “Danson Ginsberg” in cases where differences exist among parents from lower-class backgrounds regarding their children’s education. Parents of successful children show more interest and inclination towards home libraries and school assignments than parents of children who failed academically. As a result, positive parental attitudes toward school correlate positively with the academic achievement of children, regardless of the parents’ class affiliation (Makhoul, 1980).

This implies that despite the low academic level of some parents and the social and economic conditions of the family, if the relationship between parents and their educated children is positive, based on family dialogue and positive communication, including support, monitoring, and continuous encouragement, the children will succeed academically and in life.

Table No. (09): Indicates the extent of the student’s participation in family discussions

|

Repetitions |

Percentage |

|

|

Yes |

112 |

91.80% |

|

No |

10 |

08.20% |

|

Total |

122 |

100% |

Figure No. (09): Illustrates the Student’s Participation in Family Discussions

Through Table and Figure No. (09), it is evident that 91.80% of students participate in family discussions.

In this context, Ibrahim kachkouche considered mutual understanding a necessary requirement for strengthening and enhancing human relationships. Differences and conflicts arise between individuals due to a lack of understanding of each other’s perspectives (Kachkouche, 1989). Additionally, Mammoni emphasized the importance of raising awareness of prevailing relationships within the family between adolescents and parents, highlighting how a positive relationship within the family contributes to academic success (Mammoni, P 1984).

Furthermore, Schmush (1965) noted that not listening to what adolescents have to say about important matters ranked as one of the problems mentioned by a group of teenagers (Kachkouche, 1989).

In conclusion, despite various factors influencing student guidance to varying degrees and the unclear impact of parents on academic guidance, the student’s desire is an extension of the family’s desire. The family influences its children’s choice of academic specialization, even if to a small extent, through the social upbringing received by the child. This upbringing starts at home before the school years, serving as the primary stage for the child’s formative years. Mohamed AL arbi El-Nadjihi emphasizes that the family is the first human group with which the child interacts, shaping their personality during the initial formative years, an influence that remains with them throughout their life. (El-Nadjihi, 1965).

Conclusion

To improve educational outcomes with limited resources, in a short time, and with minimal effort, we must guide students based on correct scientific principles that consider their abilities and interests on one hand and the academic requirements of their chosen specialization on the other.

Reviewing the results of various studies in psychology and sociology reveals that parents often desire their children to pursue the same professions, especially parents in high-status professions such as medicine, law, and engineering. They are influenced by the social prestige of these professions.

In contrast, parents in simpler occupations usually do not impose their professional preferences on their children but may prefer their children to seek better professions. The degree of influence on career choice depends on the academic inclinations and capabilities of the children.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the hypothesis is valid, indicating that parental desires impact the academic guidance of students in the first year of high school. This influence may be indirect, occurring through social upbringing, where children become accustomed to hearing their parents’ opinions. This is articulated by Soleimane Madhar when he says: “This influence takes the form of advice: ’If you do this, it would be better …’”