Introduction

The UK’s withdrawal from the European Union is an unprecedented event, as no country has ever taken such a step. On Friday, January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom exited the EU in accordance with a Withdrawal Agreement Bill and a Political Declaration which were applicable until the end of the adjustment period in December, 31, 2020. Since then, the UK-EU trading partnerships are governed by the Trade and Cooperation Agreement that has been reached in the last week of 2020. Under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) provisions, the UK left the Customs Union and Single Market and became a third country. As a result, trade between the two parties will be subject to new formalities and this could drive to both short-term and long-term negative impacts due to the end of the four freedoms that were granted during EU membership.

As it is known, the EU is the UK’s primary trading partner by a wide margin. Consequently, there will be greater trade expenses with the rest of Europe, which makes up approximately half of UK trade. The government’s choice of a Hard Brexit, fully leaving of the EU Single Market and Custom Union, would add additional tariff and non-tariff barriers that lead to decreasing trade flows, investments, and ultimately raising the consumer prices and inflation as a result of imposing tariff and custom duties. In addition to having implications for devolved legislatures which emerged in the form of Scotland’s claim to independence.

Numerous economic studies have attempted to assess the probable economic impacts of Brexit on the United Kingdom. Some studies concentrated on the alternative scenarios of the EU membership and their socio-economic costs. Other studies provided a comparison between the benefits of the EU membership and the estimated costs of a no-deal case. The last category was concerned with the immediate effects of leaving the single market on December 2020. On the contrary, my research paper concentrates on the short and long term economic repercussions resulting from the implementation of the reached deal (TCA) at the end of the transitional phase from January 1st 2021, in addition to the interaction with the impacts of Covid-19 pandemic restriction measures that made the impacts even worse.

It is an analytical study that aims to present and analyze the short and long-term negative impacts on the British economy in the post Brexit era, emphasizing the following question:

What are the expected short – and long-term repercussions of UK withdrawal from the EU on the British economy?

To answer this central question, the following hypotheses were used:

-

Long-term effects on the UK economy will be negatively affected by the degree to which trade with the EU is hindered by tariff and non-tariff barriers.

-

Sectors that depend on cross-border interaction are those most impacted by the economic impact of Brexit.

-

The interaction between Brexit and the Coronavirus Pandemic has worsened the negative economic impacts.

The study was divided into three parts; the first part is allocated to define the term “Brexit” and presents its historical background. The second part introduces the legal frameworks that govern UK-EU post-withdrawal relationships. The last part is dedicated to displaying short and long – term economic repercussions under the terms of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA).

1. Brexit: Terminology & Background

1.1 Terminology

Brexit is a contraction of the words “Britain” and “exit”. It refers to the process of the United Kingdom departure from the European Union. England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland residents of the United Kingdom voiced their opinions on June 23, 2016 over whether to stay in or leave the EU. Brexit is the name given to this referendum (Benlabidi and Benmerabet 476). The word Brexit was coined by EURACTIV Peter Wilding’s blog post on 15 May, 2012, now recognized as the world’s first usage of the word ’Brexit’.

The Article 50 procedure of the Lisbon Treaty2009, amending the Treaty on European Union to permit the withdrawal of a member state, was triggered during the EU Referendum vote of 2016. Northern Ireland and Scotland chose to stay in the EU, whereas Wales and England (with the exception of Greater London) voted to leave (51.9% of the voting electorate), revealing the rift within the United Kingdom (Humaira1). Brexit comes in two flavors: hard Brexit and soft Brexit. Each of these leads to different economic interactions between the UK and the EU, and consequently, various economic effects.

-

The Hard Brexit: If Britain opts for a “Hard Brexit”, it would lose access to the Single Market, which includes the four freedoms of capital, goods, services and people mobility, as well as the Single Customs Union, whose members are immune from customs taxes. Hard Brexit is consistent with the UK’s objective to retain its political independence, recover complete control over its borders, and strike new trade agreements with third parties without the EU’s approval. On the other hand, it is anticipated that the Hard Brexit scenario will have significant negative economic effects on the UK economy. For instance, British exports to other EU nations would be subject to an additional 10% tax. This would drive up their cost in these markets, drive down sales. (Juneja)

-

The Soft Brexit: In order to ensure seamless trade, a “Soft Brexit” is typically understood to mean that Britain would remain closely affiliated with the EU. In reality, a “Soft Brexit” entails the option to impose restrictions on the free movement of people while nevertheless being a member of the EU’s Single Market and/or Customs Union (like Turkey). According to this scenario, Britain will formally be excluded from the European Union, which results in no parliamentary representation. In contrast, Britain will have to pay the European Union a charge in order to continue enjoying these benefits (Whitman1-2). To cut down on Brexit costs, we can define a soft Brexit as a compromise between leaving and remaining in the European Union.

2.2 Background

The stance of the United Kingdom toward the European Union and its forerunners has occasionally been ambiguous. The UK made it clear when the Treaty of Rome, establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), was signed in 1957 that it had no interest in joining the other six founding members of the EEC-France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Belgium, and Luxembourg – in building a customs union based on the European Coal and Steel Community. The UK was concerned that joining would diminish its position as a world power (Ries et al. 1).

The UK swiftly altered its mind, though, and submitted an application to join the EEC in 1961. The two times that then-French President Charles De Gaulle vetoed this application. The European Communities Act was ratified by the UK Parliament in January 1972, and the Treaty of Accession had been signed by Prime Minister Edward Heath1. The UK, along with Denmark and Ireland, was officially admitted to the European Communities (the EEC, the European Coal and Steel Community, and the European Atomic Energy Community, or EURATOM) on January 15, 1973 (Gremades and Novak 5). Two years after, 1975, Britain witnessed calls for exiting the EU.

2.2.1 The First National Referendum (1975)

The UK’s admission to the European Communities has been a contentious issue for many years. The first national referendum on the UK’s membership in the European Economic Communities (EEC) was held in 1975 by Harold Wilson’s Labor Party administration. There was political divide between pro- and anti-European Labor Party members on this topic, and 7 out of the 23 cabinet members voted in favor of leaving the EEC.

The public referendum was held on June 5, 1975 and the voters were asked to vote yes or no to the question “Do you think UK should stay in the European Economic Community?” All the regions, With the exception of Shetland Islands and Outer Hebrides, voted with yes with the 67.2% turnout in favor of continuing EEC membership thanks to strong support from the Conservative party and its leader, Margaret Thatcher, in particular (Gremades and Novak 7).

2.2.2 The United Kingdom Independent Party and the Left Behind

By the 1990s, the class system in Britain had undergone a significant shift. Tony Blair, the leader of the New Labor Party, sought to appeal to middle-class families and professionals with advanced degrees. The white working class, who had steadily lost faith in both the Labor and Conservative Parties as their representatives, was not, however, attracted to the party. These white working-class voters, also known as the “left behind”, would later turn out to support Brexit (Ford and Goodwin 60–62). The establishment of the United Kingdom Independent Party (UKIP), which ran on a platform of lowering migration flows and leaving the EU, has allowed the political left behind to lay the groundwork for a new force as the referendum date approaches.

After pressure from British political groups, such as the Conservatives, United Kingdom Independent Party, British National Party, etc., former prime minister David Cameron promised to hold a referendum if he won the 2015 general election in spite of opposing Brexit. The primary justifications were the EU’s economic downturn, the EU’s overzealous strategy to exert control over the legal systems of the UK, the absence of UK influence, and the EU’s goal for deeper integration (Vu 11).

2.2.3 The Brexit Referendum 2016

In order to facilitate the staging of a referendum on the continuation of EU membership, the UK Parliament introduced the European Union Referendum Act 2015. On May 28, 2015, Phillip Hammond, the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, delivered it to the House of Commons (Gremades and Novak 8). The legislation was approved by the House of Commons on June 9, 2015; it was then approved by the House of Lords on December 14, 2015; and on December 17, 2015, it was given royal assent. On June 23, 2016, the referendum was finally held, and the country chose to leave the EU (Gardiner and Shields 1).

The vote was narrowly approved 51.9% to 48.1%. More than 30 million people cast ballots, an unprecedented high voter turnout of 71.8%, yet there were significant disparities in voting behavior that reflected generational and geographic divides. Scotland and Northern Ireland both supported staying in the EU by 62% to 38% and 55.8% to 44.2%, respectively, whereas England and Wales supported Brexit by majorities of 53% to 47%. Numerous researchers have discovered a link between greater education levels and voting “Remain” as well as the opposite. Other surveys revealed that college graduates voted almost three to one in favor of staying in the EU, while nearly four out of five those without any formal education chose to leave (Shore10-11).

2.2.4 Triggering Article 50 and the UK-EU Divorce

On March 29, 2017, former Prime Minister Theresa May invoked Article 50 TEU, which governs a Member State’s withdrawal from the EU, based on the results of the 2016 referendum, and she reached an agreement with the EU over the divorce bill (Department for Exiting the European Union). The UK’s withdrawal deadline was extended until October 31, 2019, following PM May’s resignation. Her replacement Boris Johnson, who won the 2019 parliamentary elections with an 80% majority in the House of Commons, negotiated revisions to the departure agreement in order to pass his own plan through Parliament. On January 31, 2020, at 11 p.m., the UK withdrew from the EU as a result of the article 50 being triggered. As a result, it has entered a transition period that extends to December 31, 2020. During that period, the UK remained in the customs union and single market, but it was outside of the political structures and there was no British representation in the European Parliament.

3. UK-EU Relationships post-Withdrawal

To avoid the disastrous economic costs of leaving the EU under no-deal option, the UK has reached the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in order to maintain its long-lasting partnership with the European Union. Accordingly, we will present these agreements and analyze their costs and benefits to the UK’s economy.

3.1 The Trade and Cooperation Agreement

The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) were reached after extensive negotiations during which a “no deal” conclusion was a distinct possibility, creating a framework for the two Parties’ future economic relations. (Stefano et al. 3) The TCA went into effect on January 1, 2021, and it will be a treaty that is enforceable under international law. As a result, the UK must make sure that its domestic law complies with the TCA. “It establishes the basis for a broad relationship between the Parties, within an area of prosperity and good neighborliness characterized by close and peaceful relations based on cooperation, respectful of the Parties’ autonomy and sovereignty”. (Trade and Cooperation Agreement Art.1)

The Agreement is overseen by a UK-EU Partnership Council, which is supported by other committees. The majority of the economic partnership is covered by binding enforcement and dispute resolution mechanisms involving an independent arbitration tribunal (Trade and Cooperation Agreement Art.7-8). The TCA removes tariffs and quotas on UK goods as long as rules of origin are met. Every five years, the agreement will be reviewed and it is terminable by either party with a 12-month notice (Trade and Cooperation Agreement Art.691-692

3.1.1 Trade and Cooperation Agreement Benefits

Both UK and EU has benefitted from the reached agreement. The UK was able to totally remove itself from the EU Court of Justice jurisdiction and put a stop to free movement of people. Additionally, the agreement implies less economic disruption to trade and foreign direct investment and especially maintaining peace process in Northern Ireland. Whereas, the EU has achieved its major goal, a single deal encompassing all areas instead of the UK’s ambition for a number of separate agreements (Maddy and Rutter 16).

3.1.2 Trade and Cooperation Agreement costs

The TCA is a basic agreement with significant friction and a lack of ambition on services and the movement of people that is only intended to liberalize trade in goods, including agriculture and fisheries. “It represents a setback, going from an integrated and productive relationship to an exercise in damage limitation” (Marshall et al.3). The TCA is unquestionably a poor deal as comparison to full EU membership because it requires conditional access (checks and formalities) to the Single Market and/or Customs Union. More importantly, it is a poor bargain in terms of the goals outlined in the Political Declaration, which was adopted in 2019 and created a broad and flexible collaboration. According to Zuieeg and Wachowiak, the TCA is a precarious deal. It could devolve into a no-deal situation if one party decides to terminate it or take harsh, unilateral corrective measures. The inclusion of several grace periods, transitional periods, and reviews of (parts of) the Agreement is noteworthy, adding to the uncertainty. There are a total of 13 ways to terminate the Agreement in whole or in part. This reveals the deal’s precariousness nature (5–6).

4. Economic Repercussions of UK Withdrawal

On December, 31, 2020, the United Kingdom left the EU Single Market and the Custom Union. This would entail harmful economic consequences on the country.

4.1 Short – Term Economic Repercussions

In the short-term, additional trade frictions and disruption has occurred between the UK and the EU from January, 1 st 2021 due to new border checks and customs formalities. This will negatively affect the GDP and lead to the increase of consumer prices and the decrease of employment level.

4.1.1 Labor Market

As part of implementing post-Brexit plans (TCA), free movement of people between the UK and EU has ended and new regulatory requirements are implemented. As a result, industries which typically rely on lower-skilled workers such as retail will face difficulties due to the imposition of salary thresholds and skills requirements. Additionally, Covid-19 restriction measures have brought other changes to the labor market sourcing workers from abroad (Delloite 7).

Leaving the EU has negatively affected the GDP and lead to lower level of employment. According to the OECD Economic Survey, ending freedom of movement of EU citizens caused the loss of 3.3 million jobs EU citizens living permanently in UK, and 1.2 million British citizens living in different EU Member States (Begg and Mushövel 3). In this regard, an IFS study has showed that unemployment rate has decreased to 8-8.5 percent in Q2 2021as a result of Brexit and Covid-19.

4.1.2 The Value of Sterling

Pound sterling exchange rates with foreign currencies have moved in response to the UK withdrawal. Following the result of the EU referendum, the pound fell sharply and has not recovered its previous level. “This resulted in higher import prices, rising inflation and lower real average household disposable incomes”.(Harari 7)

4.1.3 The Prices

The UK depends on the EU for 26% of the amount of food it consumes, which means higher pricing as a result of customs. “Any price increases must be added to increased trade friction costs. All increases in cost will be borne in the first instance by the supply chain, but ultimately by consumers” (IHS Markit 4).

4.1.4 The UK Inflation

According to economic statistics as of May 18, 2022, UK inflation, as determined by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), increased from 7.0% in March to 9.0% in April. Since data have been kept in 1997, this year’s inflation rate is the greatest in 40 years. It has been increased from1.8% in 2019 to 9.0% in 2020 as it is mentioned in the table below (House of Commons Library).

Table 1. UK Inflation 2019–2022

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

Feb. 2022 |

Mar. 2022 |

Apr. 2022 |

|

|

UK |

1.8 |

0.9 |

2.6 |

6.2 |

7.0 |

9.0 |

|

Eurozone |

1.2 |

0.3 |

2.6 |

5.9 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

|

EU |

1.4 |

0.7 |

2.9 |

6.2 |

7.8 |

8.1 |

|

France |

1.3 |

0.5 |

2.1 |

4.2 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

|

Germany |

1.4 |

0.4 |

3.2 |

5.5 |

7.6 |

7.8 |

Source: (House of Commons Library)

4.1.5 The Food Supply Chain

Food supply chains have been under various pressures recently due to Covid-19, the UK’s departure from the European Union and labor shortages, climate change, and an increase in oil and gas prices resulted by Ukraine invasion … which have contributed to a rise in food prices. Since the end of 2021, food costs in the UK have increased dramatically, impacting poorer people more than others (Brigid et al.2). Post-Brexit arrangements such as border checks and custom formalities have led to inevitable delays, disrupted the food supply system and created a supply-side shock added to the COVID-19 demand-side problems. “Delays at the ports will result in missed delivery slots and will reduce the shelf life of fresh products which is likely to lead to additional losses and reduced supply. If severe enough, delays may make supply from certain origins untenable” (IHS Markit 5).

4.2 Long – Term Economic Repercussions

Longer-term refers to the ’steady state’ when the UK’s economy has fully adjusted to the terms of the new UK-EU relationship. Brexit will affect many different aspects of the UK economy including trade (goods and services), immigration, regulations, and EU budget contributions.

4.2.1 Trade in Goods

The EU is the destination of 44% of UK exports and 60% of total UK trade is covered by EU membership. Europe accounted for 51% of UK exports and 59% of UK imports, making up the bulk of UK commerce. The European Union accounted for the vast majority of UK trade with Europe - 83% of the UK exports to Europe were exports to EU countries, 87% of the UK’s imports from Europe were imported from the Eurozone (Ward 9). Following Brexit referendum, the UK has declined to the bottom of the league table in terms of economic growth among the G7, group of major advanced economies. (Fassoulas 2) Statistics show drastic economic repercussions between 2019 and 2021 as follows:

-

In 2019, the UK exported goods and services worth £291 billion to the EU (42% of all UK exports). UK imports from the EU were £371 billion (52% of all UK imports). The UK had a trade deficit with the EU of £80 billion.

-

For trade in goods only, the UK exported £171 billion to the EU in 2019 (46% of all UK goods exports). Imports of goods from the EU were £268 billion (53% of all UK goods imports). The UK had a deficit with the EU of £98 billion on trade in goods (the Authority of the House of Lords 17).

-

-In 2020, the UK was the world’s eleventh largest exporter and the fifth largest importer accounting for 2.3% of world exports of goods and services and 3.6% of imports

-

—Road vehicles was the UK’s largest category of goods export, accounting for 9% of UK goods exports fell by 29% between 2019 and 2020 (Ward 14–15).

In general, the sectors and businesses most at risk of border disruption are those that import from and export to the EU extensively:

Delays are likely at the border as traders adapt to new customs and regulatory requirements and new IT systems bed in, not helped by poor trader readiness and late delivery of key border IT systems. Lorry queues could be as long as two days. There is also a risk of widespread non-compliance with new regulatory requirements. Businesses in the UK and EU will face new rules in areas ranging from product standards to what activities are permitted on short-term business visits, and could find themselves accidentally acting unlawfully if they are unaware of the changes or have not had the time or bandwidth to prepare (Tetlow and Pope 3).

4.2.2 Trade in Services

There are no provisions in the TCA that would allow UK financial services companies entry to the single market. As a result, from the 1 January 2021, UK financial services firms lost their passporting rights. As a result, the UK service sector access to the EU market becomes more complicated compared to EU membership. The Centre for European Reform summarizes the terms for short business trips:

The TCA allows for British short-term business visitors to enter the EU visa-free for 90 days in any given six-month period, but there are restrictions on the activities they can perform. Crudely speaking, the list of permitted activities shows that while meetings, trade exhibitions and conferences, consultations and research are fine, anything that involves selling goods or services directly to the public requires an actual work visa. (Ries et al.21–22)

Without the single market, UK service providers lose their automatic right to provide services throughout the EU and are now subject to the laws of each individual EU member state. They also no longer enjoy the benefits of passporting laws, which allow access to the single market throughout the EU based on authorizations issued by one EU member state (Ward 20).

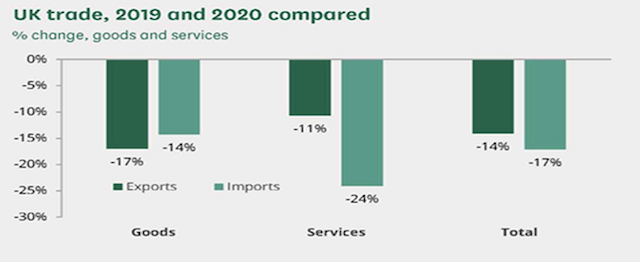

Figure N° 1. UK Trade in Goods and Services 2019–2020

Source: ONS, Pink Book 2021

4.2.3 Financial Settlements

As an EU member state, the UK had been a net contributor to the EU budget, paying in more than it received from EU programs. This payment was roughly equivalent to 0.4% of annual GDP. The UK’s financial settlement for leaving the EU was agreed in the Withdrawal Agreement and it is lower than as an EU member state. “The overall net impact on the public finances from Brexit will likely be determined by the wider impact on the economy rather than the direct savings from EU budget contributions” (Harari 12–13). The bill, which covers spending obligations made during the UK’s membership in the EU, was initially expected to cost between £35 billion and £39 billion, according to the government. Currently, Treasury Minister Simon Clarke stated that UK’s divorce bill has risen to £42.5bn, potentially adding billions to payments. He cited assumptions about inflation as one of the main drivers of the increase (Brexit: UK’s divorce bill).

4.2.4 Internal Market Regulation

Domestic restrictions have an impact on how efficiently enterprises can employ labor, money, and technology to manufacture goods. They also have an impact on cross-border trade flows, as we have noted. Some claim that leaving the EU would give the UK the chance to modify legislation to better fit its needs, increasing economic production. Certain laws, such as those governing competitiveness and state aid, are intended to promote economic output and the financial security of consumers by preventing any one corporation from acquiring and then abusing a dominant market position. John Vickers, a former director-general of the UK Office of Fair Trading, for instance, expressed fear that the UK’s exit from the EU will eliminate prohibitions on the use of state aid, leaving the government more vulnerable (Tetlow and Stojanovic16).

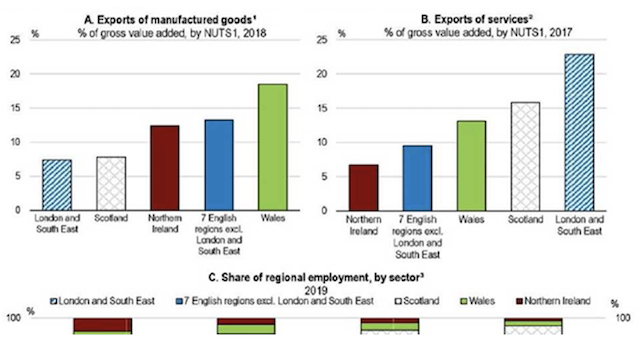

4.3 Regional Repercussions

According to a study on the geographical effects of Brexit, the North East, the West Midlands, Wales, London, and the South East are particularly vulnerable because they depend on the EU for exporting goods and services. They are particularly vulnerable to experiencing a double shock as a result of both the coronavirus and the UK’s exit. The study contends that some groups, such as blue-collar and unskilled male workers in some of the “left behind” regions, like the Northern regions, South Wales, and the West Midlands, are likely to be severely impacted by Brexit (Tetlow and Pope 11).

Figure N° 2. Regional Repercussions of UK Withdrawal from the EU

Source: (Tetlow and Pope11)

Conclusion

British withdrawal from the EU has entailed large economic costs especially from the end of the transition period and the implementation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement on January 2021. The TCA failed to maintain the UK access to the Single Market and the Custom Union. It also excluded the services sector, which makes up 80% of the British economy. Consequently, it implied a Hard Brexit option that led to the end of frictionless trade and applying checks, formalities and customs declarations. Accordingly, the United Kingdom economy has heavily been hindered due to the new arrangements that limited trade flows.

Moreover, the interaction between Brexit and the global health crisis repercussions have isolated the United Kingdom and led to a steep drop in economic outputs. As a result, the UK economy has performed worse than the Eurozone economies under the same circumstances (the Coronavirus Pandemic). Current statistics show that the UK economy will never reach the pre-pandemic levels of growth at the long term even with the supplemented free-trade deals that has been reached with non-EU countries such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. These countries contribute only 4% of commercial transactions compared to about 45–50 % with the European Union. Therefore, there are currently no effective alternatives to boost the economic growth unless achieving new trade agreements that support the services sector with the rest of the world.

Finally, the amount of immediate disruption can be reduced according to the mitigation measures and government support programs that may be implemented whenever structures, businesses, and individuals are unable to adapt. Long-term effects of the widening rift between the UK and the EU will also have a deep effect on the Irish Sea regulating border as well as on the Scottish separatism tendency. Accordingly, the UK government should seek for new financing sources to supplement the EU’s financing policies. Additionally, it is necessarily to elaborate an attractive environment to encourage FDI through renegotiations with the EU on new agreement terms that focuses on maintaining the investment flow as smoothly as feasible.