Introduction

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic led to the temporary suspension of classes in schools and universities. To ensure pedagogical continuity, a dynamic of new didactic proposals has been initiated. The solution adopted was distance learning and the digitization of programs. In the present research paper, we propose to address the following questions: how did teachers adapt to these new working conditions during the lockdown? What difficulties did they face? What pedagogical means did they use to communicate and exchange in a virtual learning environment? What is the effect of these means on the practices of teachers and on the learning methods of students? In an attempt to find answers to the above mentioned questions, a field survey was conducted aiming at investigating the pedagogical strategies adopted by teachers to deliver their courses online as well as the impact of these strategies on student learning.

This study seeks to know if teachers have the technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital resources into their teaching practices, because in Algeria the professionalization in the field of education is rather oriented towards professionalism by certification (i.e. through a diploma) to the detriment of the development of professional skills. The majority of teachers have not received training in techno-pedagogy and in the supervision of online students. It tries, therefore, to identify the difficulties they faced in ensuring their distance education, to report on the strategies they adopted to overcome these difficulties and their impact on student learning.

1. Methodology

1.1. Case Study

Our survey targeted teachers of different specialties practicing in several universities in Algeria. The majority of them answered the questions posed via Facebook groups to which we distributed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was submitted to several universities: the University of Algiers 3, the University of Ouargla and the University of Algiers 2.

1.2. Presentation of the Witnesses of the Investigation

Our questionnaire is intended for university teachers in science and human sciences. They belong to different generations: their age varies between 30 and 60 years. This diversity is important in our opinion because it allows us to know the point of view of different generations on the integration of digital resources in education. Our witnesses are teachers of various disciplines: foreign languages, psychology, sociology, law, physical education and sports, economics. They provide lectures and tutorials. Among these teachers, some hold a doctorate from the old system, others a doctorate from the LMD system. Women are legion; they are 120 in number. The men are 80 in number.

1.3. The Questionnaire Survey

1.3. 1. Motivation for Choosing the Questionnaire

We chose the questionnaire as a data collection tool because it allows information to be quantified and has other advantages: a large audience can be reached, the survey remains anonymous, witnesses can respond when it suits them best, which can facilitate their participation. We conducted a questionnaire survey on Google Forms. This investigation tool is interesting because it facilitates the design and administration of questionnaires by targeting a wide audience of teachers, moreover it is well suited to the conditions of the health situation of Covid-19 by allowing the questionnaire to be administered from a distance.

1.3.2. Introduction to Google Forms

Since scientific research is a field study that involves prospecting and deepening theoretical notions through an in-depth examination of the field, it requires the collection of information from respondents by means of a survey. The latter is based on the implementation of a questionnaire, which tends to clarify and provide answers to the research problem. Nevertheless, this scientific research remains rather flexible and adapts to the social but above all sanitary conditions of the environment investigated because the ultimate goal of research is to find answers by invalidating or confirming the initial questioning. The term Google Forms comes from the English language. Forms means in French form. It is a software that allows to administer surveys. It is part of a long list of services offered by Google. It is a free form creation tool. Its major asset is that it is easy to use, volume no longer being an obstacle. Google Forms makes it possible to collect data, organize it, analyze the results then represent it in graphic form and finally reproduce it on a Google Sheets sheet. Depending on the objectives of the research, various models are offered. Questionnaires created via Google Forms are easily distributed: “Google Forms offers sending by email, sharing a link to the document or even integrating HTML code on your web pages. (Source: https://www.blogdumoderator.com/tools/google-forms/).

1.3. 3. Presentation of the Questionnaire

As we mentioned previously, given the health situation caused by the Coronavirus, we used Google Forms to distribute our questionnaire. It is a software that allows you to administer surveys remotely.

This questionnaire contains ten (10) questions grouped under three (3) axes :

-

The tools and means used to launch an online course.

-

The management of online class times.

-

Managing the virtual interpersonal relationship.

In what follows, we propose to comment on the answers given to the questions asked (see appendix section) and to analyze the results obtained.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Tools and Means Used to Launch an Online Course

During the lockdown, the type of online education that Algerian universities had chosen to adopt to ensure educational continuity was diverse. During the first two years of the Covid 19 pandemic, fully distance education was introduced in all Algerian universities, while during the third year hybrid education was adopted. (See the question in the appendix)

To provide online lessons, teachers have chosen the following two modes of communication: Synchronous (webinar / videoconference / audioconference) and asynchronous (Email / Forum / YouTube channel / video recorder / Messaging from an educational platform, etc.). We can classify these tools in this way:

2.1.1. Communication Tools

This is the first tool to have. It is used to transmit important information on the courses upstream, invite learners to videoconferencing tools. This may be :

-

A website, to inform about the course offer,

-

Whatsapp groups, for alerts, short written exchanges,

-

Emails, to invite learners to videoconference sessions.

2.1.2. A Video Conferencing Tool

There are many videoconferencing solutions:

-

•Zoom

-

Teams

-

Skype

-

Meet

-

Jitsi

But the most used tools for the animation of online courses in Algerian universities were: Zoom, Meet and Skype.

2.1.3.A File Sharing Tool

For the exchange of files, written productions, oral productions, it will be necessary to go through another tool. File sharing solutions are numerous. This can pass simple sharing systems:

-

Google Drive

-

One Drive

Dropbox Or by LMS (online learning platform):

-

Apolearn,

-

Blackboard

-

Moodle, used at all Algerian universities.

The teaching / learning modes that our witnesses have adopted in their online courses are diverse, we have classified them as follows ((See the question in the appendix):

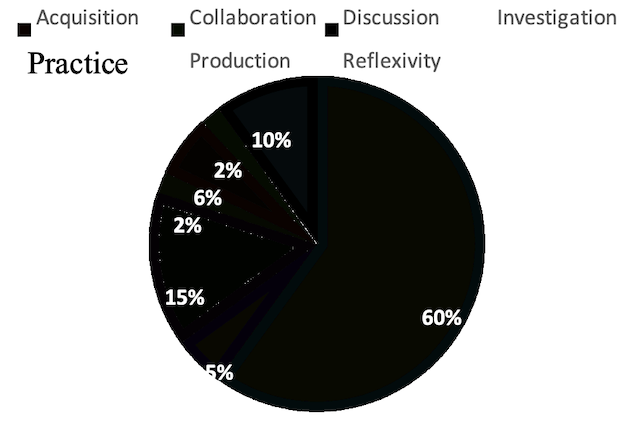

-

By acquisition: Reading of texts and narrated Word/PowerPoint PDF courses/listening to an educational video/video of lectures, etc. (60 %)

-

By collaboration: team project/problem-based approach/collaborative glossary/collaborative wiki, etc. (5 %)

-

By discussion : Discussion forums.(15 %)

-

By investigation: Survey/collection and analysis of data/comparison of texts/documentary research, etc. (2 %)

-

By practice : Exercises/MCQs (multiple-choice questions)/Online role-playing games/simulation, etc. (6 %)

-

By production: Report/minutes/dissertation, thesis/portfolio/production of a video/production of a text; video, media playback (2%)

-

By reflexivity/metacognition: Reflection in relation to personal or group work/self-assessment/peer assessment/solving a complex task in a group (10%)

Figure 1 : Teaching-Learning Mode

These results reveal that prior knowledge is necessary to establish the content of the online course, the teachers develop a meta-discourse based on the already-known and the already-there of the students. The back and forth between the discourse of the teacher and that of the student is at the heart of the teaching activity. In the socioconstructivist model, the acquisition of knowledge involves the transformation of the learner of his previously acquired knowledge and the reorganization of his initial conceptions. The acquisition of knowledge by the student is not a memorization of information provided by the teacher but an activity of filtering and interpretation of the knowledge already acquired. The knowledge in didactics is not transmitted passively but built by the experiences lived in its environment.

To interpret these results, we will rely on the theory of reflexivity. This notion is defined by several authors and is part of several disciplinary fields. In the broad sense, reflexivity refers to “a return to oneself”. In the educational field, the definitions of reflexivity come from two traditions. The first relates to the sciences of education and the other relates to the field of language teaching which favors “dialogical” reflexivity (Daunay and Treignier, 2004) observed in teaching practices. In the context of our study, the teachers are in a position to ask for a “return from the subject to the object by which the subject turns to his own operations to submit them to a critical analysis” (Vandenberghe 2006: 975). It consists of the interaction between thought and action mediated by language (Bibauw, Dufays 2010). Therefore, teachers must adopt means to “enable learners to develop advanced reflective capacities” (Bibauw, Dufays 2010: 19). This is a way of providing them with good training and preparing them to become independent.

It should be noted that in the field of professional teacher training, the notion of reflexivity is mainly understood in connection with the work of Schön on the “reflective practitioner” (Schön, 1996). This notion is a “form of thought present in the action of professionals, verbal and explicit: ‘reflection on action’” (Vanhulle, 2009: 260). The “reflective practitioner” therefore reviews his action, during or after it, by adopting a distant and critical posture that allows him to improve (Paquay et al., 2004).

Following Bibauw, Dufays (2010), we can talk about reflexivity as an end or reflexivity as a tool. Indeed, the first supposes that we develop in the learner a reflective posture. As a result, learners are encouraged to take charge of their own relationship to the object, to evaluate their progress... (Vanhulle 2004). The second is combined with intersubjectivity in the moment of individual work.

2.2. Online Class Time Management

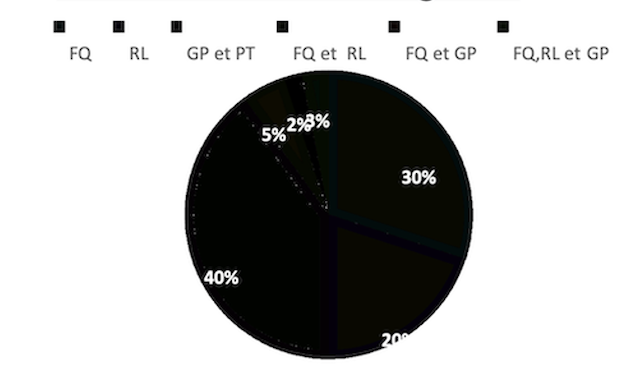

The answers of the witnesses, to the question: “How to manage the moments of online dialogue course”?, are distributed according to the following three choices:

-

In the formulation of questions (FQ);

-

In reminders to the learner (RL);

-

In the management of power point (GP) and the posture of the teacher (PT)…

Figure 2 : Online Class Time Management

60 teachers answered that the management of the moment of dialogue in online lessons goes through the formulation of questions. 40 of them see that this management is done through reminders and 70 others think that these moments must be managed with the management of the power point and the posture of the teacher. We also found answers that fall under two or three choices at the same time two or three choices. Thus, 20 teachers think of the formulation and the reminders, two of them consider that the formulation and the management of the power point are important to manage the moments of dialogued courses online while the 10 remaining merge the three postures: formulations of the questions, reminders from learners and power point management.

2.3. Virtual Interpersonal Relationship Management

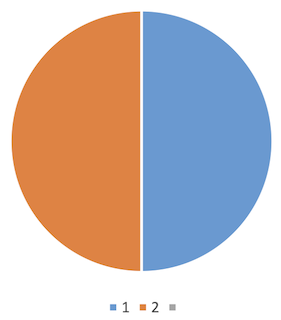

The question we asked the teachers is: How to know how to manage the virtual interpersonal relationship? We asked them to choose the correct answer between: “By knowing the first names of the students (1)” or “By receiving questions from the students (2)”.

100 teachers chose the answers: knowledge of first names and reception of students’ questions and 50 others affirm that only the reception of students’ questions is important in the management of the interpersonal relationship. 50 teachers consider that knowing students’ first names helps to manage the relationship between teacher and student.

Figure 3 : Virtual Interpersonal Relationship Management

The majority of teachers confirmed that managing the teacher-student interpersonal relationship is very difficult given the heterogeneity of the groups and the uniqueness of each learner. Each student being a particular learner, the teacher is obliged to manage this (these) particularity(ies). Faced with the heterogeneity of the students, the teacher should admit that there are several cognitive hypotheses in the process of acquisition which do not necessarily correspond to his own. In short, it is a question of involving the students more and of getting involved by formulating/reformulating certain instructions.

The majority of teachers questioned are in favor of involving all students by knowing their first names. A minority of teachers opts for the formulation/reformulation of instructions. However, reformulation remains one of the main characteristics of didactic and popularization speeches because of their important, even essential, contribution to the transmission of knowledge "It is anchored in a psychological act which requires the transmitter to always be afraid that his speech comes up against the incomprehension of the receiver, which is why he sometimes feels the need to reformulate it, that is to say to say it differently. (Affeich, 2009:164).

Conclusion

The survey that was conducted by addressing a questionnaire to a number of Algerian university teachers revealed that they are aware of the importance of their role and their involvement in the act of online teaching-learning as well as the impact of collaborative work with their peers. As a result, they reflect on the behaviors they adopt and the improvement of their teaching practices in their online course. Thus, they ask questions about their students’ prior knowledge, involve them in the formulation of instructions, adopt different strategies to arouse their interest: use of the Moodle platform, use of student social networks, interpersonal communication via different digital applications. The teachers subject to our survey also say that they are able to manage their online course by using teaching tools already used in face-to-face lessons. Possessing applied knowledge on how to teach and general knowledge on teaching/learning, they believe that it is important to adopt a reflective look at their teaching practices and at the learning strategies of their students in order to overcome the Obstacles, fill in the gaps and remedy the difficulties that students encounter when launching the online course.

Therefore, several challenges must be met to successfully teach an online course:

-

The challenge of student autonomy. Taking a fully online course requires a lot of autonomy from the students. It is therefore important to clearly identify their learner profiles on the cognitive and socio-emotional levels, in order to anticipate their possible difficulties and to provide them with resources aimed at making them more autonomous and persevering.

-

The challenge of an explicit pedagogy. For the student to be able to progress by himself, the educational scenario must be explicit. Particular attention must be paid to the formulation of the learning targets as well as to the proposed learning process, while leaving the student the possibility of making choices and of contextualizing his learning process, according to their interests, needs and goals.

-

The challenge of collaborative design. The design of such a course requires mobilizing a diversity of skills. Even if he remains solely responsible for his course, the teacher benefits from benefiting from the expertise and experience of other actors (tutors, teaching professionals, programmers, graphic designers, multimedia specialists, etc.).

-

The challenge of media coverage of the course. The options available to the teacher today regarding the media format to be given to the course and the activities that can be carried out remotely are multiple. It is therefore necessary to make an informed choice in terms of media coverage, motivated above all by educational concerns.