Introduction

Since the early 1990s, ESP has grown to become a prominent area of English language teaching. A great demand for English language has emerged due to the continuous economic and technical revolutions in a twenty-first century world dominated by globalisation. As a result, countries around the world, and Algeria is no exception, have integrated ESP within its national curricula in higher education institutions.

In Algerian tertiary level, General English (hereafter, GE) teachers and English doctoral students are often relied upon to teach English for students majoring different disciplines and having various needs and interests. Yet, most of them have no prior training or experience to cope with the ESP teaching requirements. ESP in general, and EBE in particular, have been strictly associated with students’ needs analysis as courses should be tailored according to learners’ needs in a certain field of study. ESP, therefore, requires teachers who are equipped with necessary skills including, specialised language knowledge (hereafter, SLK) being taught, selecting the appropriate course materials, language pedagogy, etc. to effectively meet their learners’ demands.

In the Algerian context, Mebitil (2011) identified a number of problems encountered by ESP teachers in Tlemcen University, that can be attributed to the students such as, heterogenous classes, the lack of motivation; to the teachers like the lack of content knowledge, absence of training and lack of collaboration among ESP teachers and with subject specialists; and to the administration like short course duration and syllabus’ absence. However, her study is rather broad because it involved ESP teachers from different departments with varying teaching conditions.

Recently, a study done by Sartorio and Hamitouche (2021) in Ghardaia University with a number of business English teachers. Their study revealed that the biggest encountered problem is the students’ poor level of English, absence of teachers’ training and many other issues. Similarly, Saraa’s (2020) study showed that ESP teachers in technical departments in some Algerian universities encountered considerable obstacles in the process of syllabus design such as lack of training, syllabus models and documentation. Despite the studies success in highlighting key ESP challenges from large number of teachers-participants, it would be more thorough if the interviews were used to analyse the problem in more depth.

To date, little attention has been paid to ESP teachers’ needs and challenges as ESP literature, especially in the Algerian context (Afia and Abdellatif Mami, 2020; Belmekki and Bensafa, 2016; Benabdallah, 2015; Kherrous and Belmekki, 2021; Lamri, 2020), has tended to prioritize students’ needs and course design over teachers’ needs and education. Nonetheless, existing studies on Algerian ESP teachers’ challenges were mainly quantitative, and focused on the main general challenges faced by ESP teachers. It is therefore of interest to gain more evidence about the challenges, particularly those related to SLK and course materials as they are the most critical aspects of ESP teaching.

1. The Role of ESP Teacher

Because ESP in general, and EBE in particular, must be targeted to the students’ requirements, an emphasis is placed on the fact that ESP practitioners’ role extends beyond being a language teacher to collaborator, researcher, course designer and materials’ provider, and evaluator (Dudley-Evans & St. John, 1998).

1.1. ESP Practitioner as a Teacher

The initial role as a teacher is the same as the ’General English’ teacher. That is, the ESP teacher teach students the basics of language to be able to employ academic and professional jargon, as well as terminology specific to certain genres. Additionally, ESP teachers aim to raise students’ awareness of the communication strategies they use in their daily lives by emphasizing the importance of the four macro- skills (listening, writing, reading, and speaking).

1.2. ESP Practitioner as a Course Designer and Materials Provider

Typically, the ESP teacher is in charge of selecting teaching materials for his/her students. This entails selecting an acceptable course book or collection of materials when they are available, altering a current textbook or set of materials to make them fit for use with a specific group, or developing content where none is available, as in the Algerian context. There is very little subject-specific literature available, therefore ESP practitioners may need to create their own. In addition, ESP teachers must evaluate the efficacy of the published or self-created teaching materials utilized in their courses. It describes an intriguing skill needed of the practitioner: the teacher must be able to produce and apply accurate content based on the situation and the requirements of the students.

1.3. ESP Practitioner as a Collaborator

The role of the ESP practitioner as a collaborator is associated with working closely or collaboratively with subject specialists to fulfil the unique requirements of the learners and appropriately adapt the target discipline’s methodology and tasks. Moreover, it is difficult for ESP teachers to obtain resources or even construct a syllabus on their own, therefore they require the assistance of a specialist teacher to help them grasp the topics and locate materials. When team teaching is not an option, the ESP practitioner should work more closely with the students, who will be more familiar with the specific content of the materials than the instructor. The most complete collaboration occurs when a topic specialist and a language instructor co-teach lessons.

1.4. ESP Practitioner as a Researcher

The ESP practitioner has another role as a researcher, or at the very least in keeping updated with the expanding body of research done and published in ESP field (Dudley-Evans and St John, 1998). The function of a researcher entails conducting a students’ needs analysis, which is the keystone of an ESP course, that determines course and syllabus design, material selection or adaptation, and evaluation methods. According to (Abedeen, 2015), undertaking needs analysis requires from ESP teacher a thorough insight into the research methodologies and the philosophical perspectives that support them, as well as an understanding of the evolution of needs assessment and its goals and objectives in ESP.

Furthermore, ESP practitioners are recommended to go beyond defining specific target activities, abilities, and texts to " to observe as far as possible the samples of the identified texts” (Dudley-Evans and St John,1998) in order to better grasp the different types of discourse and genres that students utilise in their field of study.

1.5. ESP Practitioner as an Evaluator

An evaluator is the last vital role that an ESP practitioner should perform. Students are tested, and courses and instructional materials are evaluated. Evaluation in ESP involves students’ assessment to examine their comprehension of the nature of language usage in target contexts, as well as their mastery of the skills required to exploit the language and complete specific required activities. In addition, ESP practitioners have to evaluate the course’s efficiency by determining how much students have benefited from the course. Dudley-Evans and St John (1998) emphasized that evaluation should take place during, at the end of the course, and after the course has completed in order to determine if the students were able to apply what they have learnt and to identify what they were not equipped with. This type of continual evaluation enables teachers to adjust their syllabus and enhance the effectiveness of their courses. Furthermore, the process of assessing ESP teaching materials requires that practitioners aim to evaluate the efficacy of the content and the amount to which it satisfies the students’ expectations (Hutchinson and Waters, 1987).

2. Methodology

As EBE teachers are required to equip the students with the necessary knowledge and skills to better perform in their academic and/or occupational careers, this study is an attempt to explore the challenges encountered by EBE teachers at University Centre of Maghnia (hereafter, UCM), especially those issues related to SLK and course materials. By applying a qualitative methodology, this study seeks to address the following question: What are the challenges encountered by EBE teachers, especially those concerning SLK and course materials?

2.1. Participants

Five teachers from the Institute of Economic, Commercial and Management Sciences at UCM were interviewed during the first semester of the academic year 2020-2021, and four teachers were observed in their EBE classes during the second semester of the same academic year. All respondents verbally consented and signed a permission form to participate in the current investigation. Table1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of EBE teachers who took part in this study. To maintain participant confidentiality, the authors use the abbreviations P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5 to refer to the teachers-participants.

Table 1. EBE Teachers’ Profile

|

Participant (No.) |

Gender |

Age (Years old) |

Teacher’s qualification |

EBE Teaching experience (years) |

GE Teaching experience (years) |

|

P1 |

Male |

33 |

Magister degree and a PhD student in Sociolinguistics |

7 |

4 |

|

P2 |

Female |

40 |

Magister degree and a PhD student in Sociolinguistics |

17 |

1 |

|

P3 |

Male |

64 |

-Magister degree and a PhD student in African Civilisation. -BA in translation and interpreting |

11 |

39 |

|

P4 |

Female |

30 |

Doctorate degree in Literature |

5 |

6 months |

|

P5 |

Female |

26 |

Doctorate degree in Didactics and assessment in English Language Education |

1 |

3 |

2.2. Data Collection

The study’s data were collected through semi-structured interviews and classroom observation. Semi-structured interviews were used to get in-depth information about EBE teachers’ challenges. Face to face and tape-recorded interviews occurred in the teachers’ room at UCM’s library, and ranged in length from 40 to 60 minutes. The questions were open-ended, and not fully restricted to the prescribed interview’s questions in order to encourage the participants to feel at ease and increase a certain amount of natural conversation.

The semi structured interviews were supplemented by using a classroom observation checklist to assess a number of challenges concerning teachers’ SLK, the course materials used, teaching methods and techniques, teacher- student interaction and classroom management. Observation serves as reality check because what people say they do may be different from what they actually do (Robson, 2002 :310). Classroom observation provides valuable insights, more detailed authentic data and precise evidence about how EBE teaching situation takes place in UCM. It allows to see EBE teachers’ challenges in the real naturalistic setting, and how they overcome them.

2.3. Data Analysis

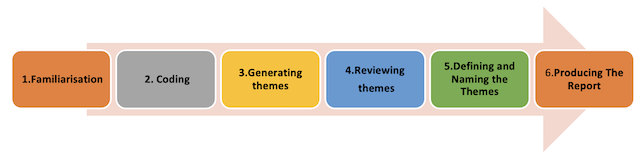

Following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis (hereafter, TA) framework, qualitative data were analysed using a hybrid approach of deductive and inductive coding. The analysis deductively started with a set of codes, driven by the research questions and then generating inductively additional codes from the data itself.

This framework is arguably the most influential approach as it is clear and accessible for undertaking TA. Braun and Clarke (2006 : 4) described TA as “a flexible and useful research tool, to provide potentially a rich and detailed, yet complex, account of data”. Because of its flexibility, TA approach allows the researchers to identify patterns and generate new insights from the complex data set. Data were coded and categorised into sub-themes to identify core themes using the analytical process of TA which includes six phases which are clearly indicated in figure 1. The first phase is about data’s familiarisation through repeatedly reading the observation notes and teachers’ interviews transcripts. This phase allows to actively observe the patterns and meanings throughout the data. The second phase involves creating initial codes which represent brief descriptions or titles of what has been said or done. The codes should be created according to the similar meaning of the data excerpts. Generating themes is the next phase which includes the formation of different categories and broad themes. This operation helps to visualise the connection between the codes, sub-themes and core themes. The researchers make a transition from codes to broader themes by combining the initial created codes. The next step is reviewing themes, which involves the examination, modification, and development of the basic themes discovered in third phase. This is essential to compile all pertinent data for each theme and/or category. The fifth phase includes defining and naming the identified themes. Themes’ names should be descriptive and definitions explain why the themes are noteworthy. This step also determines the correlation between the themes and subthemes as well as their relation to the overall research question. Producing the report is the final step in which constructs the narrative that explains the findings. As shown in the section bellow, the authors identify all the themes and subthemes emerged from TA including, some vivid excerpts and interpretive analysis to support and reinforce the validity of the results.

Figure N° 1. Six-Phases Framework of Thematic Analysis

Source : Braun and Clarke, 2006,35

3. Findings and Discussion

The findings revealed various challenges faced by EBE teachers at UCM. In order to capture the crucial features related to the addressed research question (Braun & Clarke, 2006), five core themes emerged from TA namely, the unfamiliarity with SLK, the total absence of ESP training, the lack of teaching materials, challenges concerning the students, and challenges concerning the organisation and administration.

3.1. The Unfamiliarity with Specialised Language Knowledge

The first emerging theme is about teachers’ inadequate knowledge of SLK. All participants claimed that they had a difficulty in getting familiar with SLK, especially the terminologies as shown in the following excerpts:

“I have the problem of the lack of SLK, be it written or spoken. I have no knowledge or interest about business and economics, banking, management, etc. Now I am obliged to acquire a knowledge to teach my students” (P5)

“At the very beginning, I needed to know concepts and definitions because I did not know anything about EBE terminologies.” (P4)

“This is the challenge, a teacher of English in Economics department. For someone who begins teaching EBE, it is so hard and difficult. It was new for me as we are not economics specialists.” (P2)

“I had a lack of the subject knowledge and in understanding specific terminology, acronyms and abbreviations especially at the beginning” (P1)

EBE neophyte teachers have a deficiency in SLK as their background studies are different from EBE teaching requirements. This can lead to many obstacles in designing the course. Thus, they are required to widen their SLK through learning and professional development in order to effectively operate in their classrooms. To become more familiar with the content knowledge, all participants mentioned that they have learnt it by themselves especially at the beginning of their EBE teaching experience:

“I did my efforts like anybody who begins to do something new for him … when I started to teach EBE, I was teaching and learning at the same time.” (P3)

“To overcome this problem, we have to get used to it and to be experienced through the years … firstly, I acquired terminologies while preparing my lessons so that to make students knowing them” (P4)

“I have learnt it through my teaching experience” (P1)

Because EBE teachers’ professional role can be influenced by the lack of SLK, they are required to develop it to reach their course objectives and fulfill their students’ needs and expectations. They can use many strategies to expand their knowledge through reading, making research, and through teaching experience as well. If EBE practitioners are competent enough in SLK, they will easily achieve their teaching purposes as they have to equip their students with the necessary knowledge related to their future target situations. Hutchinson & Waters (1987) argued that ESP teachers may have a dilemma of mastering the content knowledge which is different from their own previous experience or formation. ESP teachers must be competent in SLK in addition to pedagogical and English language competency, so that to be successful and effective in their teaching (Maleki, 2008). As the participants have a GE profile (see table 1), They face the challenge of knowing little or nothing about EBE knowledge. So, they find themselves teaching students with a specialized English variety which they have never taught.

SLK is certainly necessary for EBE teachers, notably the specialized terminology, as it is the primary defining aspect of EBE discourse in comparison to GE discourse:

“I have a SLK problem in all language levels, but the terminology is the main concern. If I get the EBE vocabulary the other levels will be easy to grasp… I also have a difficulty in understanding acronyms and abbreviations.” (P5)

“The main difference between EBE and GE language knowledge is in vocabulary” (P1)

“The difference is more remarkable in concepts and terms” (P2)

“We tend to use more acronyms as words in EBE, such as CEO for Chief executive Officer, WTO for World Trade Organisation, etc.” (P3)

It is noticeable that participants believed that lexis was the most crucial part of EBE knowledge. As a matter of fact, EBE terms are more technical and complex in nature than GE ones. Thus, they require more time and efforts to learn them. Additionally, the fact of being unknowledgeable in EBE influences teachers’ self-esteem and rises their confusion, stress and insecurity. This was reflected on what the following participants mentioned:

“When I began to teach EBE, I was afraid to do mistakes in front of my students.” (P4)

“There are students who ask me questions that I do not master… But I do not show them that I am panicked.” (P2)

“I had major difficulties because I am not familiar with EBE.” (P5)

Similarly, Iswati and Triastuti (2021 :284) asserted that the lack of SLK influences ESP practitioners’ tension and anxiety. Lack of expertise in specialized knowledge hinders EBE teachers from adequately teaching in class, which affects students’ trust in the teacher.

Participants also expressed that they have a problem of the lack of collaboration with subject matter teachers:

“In principle, teachers should normally collaborate between each other. But here we do not have that kind of collaboration” (P2)

“It is another big issue. There is no collaboration with business and economics teachers” (P5)

“No not really, but it would be good to have collaboration” (P1)

“No, I do not have any collaboration with them” (P3)

Collaboration, whether with topic specialists or with EBE instructors themselves, is essential to increase their acquaintance with the content knowledge. Teachers can exchange thoughts and guidance regarding language pedagogy and EBE teaching techniques and methods. This further validates the findings from previous studies (Alsharif and Shukri, 2018; Ghezali, 2021; Mebitil, 2011) that collaboration benefits ESP practitioners by reducing the need for specific language expertise and pedagogy-related issues. Additionally, participants claimed that EBE teachers have to collaborate with their students:

“I have also acquired it through communicating with my students. I even learnt from what my students know as they are specialists in their subject matter” (P1)

“We learn from our students”. (P2)

“I acquire it from my own learners as well” (P3)

In their attempt at developing expertise in SLK, EBE practitioners are advised to collaborate also with their students who are considered, to a certain degree, as experts or familiar in their field of study than the EBE teachers themselves (Bracaj, 2014). In this regard, (Robinson, 1991) described that ESP teacher is not, straightforwardly, the only source of information, but the learners will be significantly more knowledgeable in their field of expertise than the teacher. Besides, collaboration can reinforce the teacher-student relationship inside and outside the classroom, and increase students’ motivation. Though all EBE teachers perceive collaboration as a significant practice in teacher’s professional development, they do not engage in it for certain reasons as shared by one participant:

“Sometimes I want to do, but there are some teachers who are not ready, or do not devote their time to others because of their responsibilities, teaching elsewhere, etc.” (P3)

They believed that any EBE teacher can learn SLK by himself/herself through making research, readings, watching videos, and mostly through teaching experience. This is actually what was observed during the classroom observations. Because of their significant teaching experience as EBE teachers, P1, P3 and P4 seemed knowledgeable and could equip their students with the necessary knowledge. For instance, P3 who has had almost 10 years’ experience in teaching EBE, showed a good command of SLK. During his courses, it was observed that he can easily define and explain the most complex EBE terminologies, and exemplify from the real context. However, being a novice EBE teacher, Participant 5 showed a limited expertise of SLK.

3.2. The Total Absence of ESP Training

Another important finding, which affects EBE teachers’ qualification and SLK is the total absence of training. All participants reported that they have not undergone any kind of prior ESP training as demonstrated in the following excerpts:

“No, never. I switch directly from GE to teach EBE.” (P1)

“No, never. I have been teaching EBE by using my own efforts. I have made my own lessons” (P2)

“No, I have been learning by myself through practice. We do not have ESP formation programmes in Algeria … But, I have been trained by GE inspectors and I got also a training on English language teaching at the institute of Hasting in England. We learnt how to teach GE and things related to teaching pedagogy”. (P3)

“No, I have never had a training on teaching EBE.” (P4)

“No, I did not have such kind of training. However, we had a module about needs analysis in which we learnt the basics and ESP theory.” (P5)

The fact of being untrained makes EBE teaching practice much more challenging to deal with the new teaching demands. Teaching EBE requires well-trained practitioners to reach the desirable teaching outcomes, but training programmes in Algeria are absent or rarely implemented. Thus, EBE teachers expected to be knowledgeable on the field being taught to design the appropriate courses, and to adopt the right teaching methodologies and techniques to fulfill their learners’ needs. Training can minimise the problem of the lack of SLK, and prepare ready and qualified ESP practitioners who can fulfil their students’ needs and equip them with the necessary knowledge related to their future target situations. Through training, teachers can know what EBE teaching really is as most of them reported that they focus mostly on EBE terminologies in their courses. ESP is not only about specific terminologies, but how they function in the discourse of a specific social community.

“Most of the time I give them the definition of the concepts related to the lesson.” (P1)

“I always incited them to memorise the terms” (P3)

All participants agreed that training is the best solution to overcome all the challenges that any practitioner will come across while teaching in EBE classroom. Furthermore, they urged for implementing ESP training programmes that incorporate all aspects from theory to practice. In this concern, P3 suggested that training should last long to be efficient for teachers-trainees:

“Training is the best solution, and it should be long… Even if there were some training programs done in the field, it was not well-done and the duration was not sufficient. Furthermore, maybe the teachers who were chosen to train are not themselves qualified. Not because you are a doctor or a professor, you will be automatically successful in training others. Training and teaching are different”. (P3)

Richards, Richards, and Farrell (2005 :3) considered training as a series of activities that should be determined by experts, and primarily centered to the current responsibilities of teachers-trainees. Thus, training courses should be designed to fulfil practitioners’ needs and equip them with the necessary skills to effectively function in their EBE classrooms.

Because such training programmes are absent in Algeria, EBE teachers need to be autonomous and to professionally develop themselves by themselves in order to switch from GE to specific English (i.e., EBE). In this respect one participant claimed:

“If you are a good GE teacher, and you are prepared to learn, you can teach ESP like Business English… But I have to overcome these obstacles through preparation. As it is said if you want to teach, you must have good selections, preparation, presentation and assessment; because we are not born as teachers.” (P3)

Robinson (1991) believed that flexibility is one of the key attributes that ESP teachers should possess. Flexible teachers are those who can successfully make a transition from teaching GE to teaching ESP. They should cope with different learners’ needs and expectations, manipulate the teaching methods to reach the learning outcomes, make efforts to learn the SLK and be aware of the professional tasks that their students are engaged in.

3.3. The Lack of Teaching Materials

One of the main pillars of ESP in general, and EBE in particular, is designing the suitable materials. These latter can be selected, adapted, written and developed. Materials refer to anything that can be utilized to make learning a language easier (Tomlinson, 2012 :143). Through materials, the EBE practitioner can equip the learners with the necessary knowledge and prepare them to appropriately communicate in their expected future business situations. Thus, teachers should expose their students to as much authentic materials as possible (i.e., derived from real business life contexts) and primarily relied on students’ needs.

All EBE teachers complained about the absence of teaching materials, as demonstrated in the following examples:

“Course materials do not exist completely and I have to search for them by myself” (P4)

“There are no EBE teaching materials. We have to plan the lessons and provide materials by ourselves.” (P1)

“Here most available books in the library are dictionaries … But they do not have EBE textbooks” (P3)

Because the non-availability of materials, including textbooks, the teaching task becomes more challenging and harder for EBE teachers. They are also not trained before on how to design the suitable materials for ESP students. Moreover, they did not get any support, guidance or orientation, be it from other EBE teachers or content’s teachers. To overcome this challenge, they all claimed that they usually use the internet where a plethora of ESP resources and materials are available.

It is also worth discussing that the absence of a systematic analysis of students’ needs is one of the reasons that make materials selection hard and challenging for these EBE teachers. The interviews revealed that teachers did not conduct a systematic or an adequate needs analysis. The following excerpts demonstrate their claims:

“Actually, no. I do not do an official needs analysis using tests and questionnaires, etc. By time I know from their performance in class, so I guess generally what they need” (P1)

“What do you mean by needs analysis?” (P4)

“I do not do a needs analysis especially for master students who are heterogenous and numerous” (P3)

“We began the year with virtual classrooms. I just gave them an exercise which can be considered as a test. The results showed that they are beginners” (P5)

This can be explained mainly by two factors. First, these teachers have different study background from ESP/EBE (as shown in table 1). For instance, P4 does not even know what needs analysis means because she is specialised in literature. Second, they have not undergone any prior ESP/EBE training in which they are supposed to tackle the aspect of needs analysis. This, in principle, can make teachers unaware of needs analysis’ necessity and importance in selecting the appropriate materials, adapting the adequate teaching methodology and techniques, and reaching effective course’s outcomes. Dudley-Evans and St. Johns (1998) asserted that needs analysis is the corn stone of ESP to identify the course’s goals and objectives, and it is critical in Business English in contrast to other sectors or types of English language. Business English students are more diverse, making it difficult to estimate their language abilities (Martins, 2017). Because the selected materials should be tailored according to the learners’ needs, teachers have to gather and analyse evident information from students and stakeholders rather than relying on their intuition or common sense.

Though innovative needs analysis models have been created by many researchers interested in ESP students’ needs in many fields, but their results remain in the theoretical level. Hence, these findings should be used by syllabi and materials’ designers to create high-quality ESP curricula and effective course materials.

A further finding highlighted that EBE teachers faced the issue of the lack of teaching equipment:

“Now, we have the problem in the technological devices which are not sufficient. In order to get a data show projector, you have to wait, queue, or do a booking in advance” (P3)

“I tried to apply some listening activities but I could not because of timing and the lack of equipment. There are no head speakers and data show projectors.” (P5)

This was also detected during classroom observation. P3, for example, faced a problem in delivering his lesson with “master 1” students (specialty of Monetary and Banking Economy). He was obliged to deliver his lesson which encompassed some visual aids and a power point presentation without a data show, because he found that the projector cable was broken.

Another observed problem was the teacher’s (P3) low voice as there was no microphone, and all his observed lessons took place in the amphitheatre. These observations are limited to UCM, and cannot be extrapolated to all Algerian universities. Obviously, using teaching aids (i.e., audio, visual, or audio-visual) are one of the methods that make language teaching more efficient, and it can engage students to participate and make them more active in classroom. UCM institution should raise funding for EBE/ESP courses to cover the costs of providing equipped language labs, ICT tools and purchasing EBE instructional materials including textbooks and dictionaries.

3.4. Challenges Concerning the Students

As far as students are concerned, low English proficiency was one of the serious challenges that EBE teachers have faced in UCM. All participants reported that the majority of students, in all grades, have low level in English and a poor grammar:

“The difficult thing that I have encountered was the level of students. I can say a bad level of English” (P2)

“They are beginners. Just a few of them who are intermediate. They do not know even the objective behind learning English in their field… They have a poor grammar and they hate it” (P4)

“They are also poor in grammar, for instance, the use of tenses. Even though I did a revision for them about present simple which is the simplest tense, but they often do the same mistakes in their copies.” (P5)

Classroom observations revealed students’ poor performance in all English language skills (i.e., listening, reading, speaking and writing). This can be reflected in the lack of teacher-student interaction. Teachers tried to engage them by asking questions, but very few who could respond. They frequently replied in French or Arabic, with brief sentences or single words. Furthermore, they had a French interference when pronouncing words or reading aloud in English.

This may raise concerns about the Algerian educational system in middle and secondary levels in which they study all GE basics. The syllabi and teaching materials of English are believed to be inappropriate and should be redesigned to meet the desired courses’ objectives. Teachers also should be well-trained and equipped with necessary skills to fulfil the needs of middle and secondary’ pupils. It is important to highlight the fact that English subject is neglected by most of pupils as they consider it difficult and unimportant. Additionally, the geographical areas that students come from also plays a significant role in the low English proficiency. The students come to university with a poor grammar and a low language background. Broadly speaking, those who come from urban areas tend to be more competent in English as they have the chance to do extra courses of English in private schools than those coming from rural areas.

If students have unsolid foundation in GE, it will be so difficult for them to grasp specialized English (i.e., EBE) in tertiary level. ESP instructors commonly face students who lack basic language skills. For instance, Poedjiastutie (2017) claimed that due to the learners’ lack of English language competency, ESP practitioners must teach GE instead of ESP. Because of students’ low English proficiency, classroom observation and interviews revealed that teachers use Arabic or French translations especially for EBE technical terms to be understood and to attract their attention:

“I usually start with English medium, then explain what have been said in Arabic” (R1)

“I use English but I do feel that they are completely out. So, I am obliged to code switch and even exemplify using Arabic or French” (R5)

A similar pattern of results was obtained in Abedeen’s (2015) study. She asserted that most ESP teachers in Kuwait are compelled to choose Arabic as the language of instruction because of the pressure of dealing with students’ English limited proficiency.

It is interesting to note that what makes EBE teaching situation double-challenging is the gap in language proficiency between students. Baker and Westrup (2000) argued that it is not just the fact that there are many students in a class, but that all of them are multileveled which provide the biggest challenge. That is, class heterogeneity or mixed-ability classes which was confirmed by participants:

“In language proficiency, what we can say is that their levels might differ. There are poor and good students” (P1)

“They are mixed ability classes. The majority are beginners. Some others are underachievers, and cannot even understand what I am talking about during the lectures… Very few diligent students who are intermediate, and can work hard and love learning English.” (P5)

Students’ heterogeneity, as pointed out by P4, is because of their backgrounds, coming from different schools and taught by different teachers. According to Ur (2012), a mixed ability class contains a variety of learners with varying levels of intelligence, experience and learning styles. Thus, such classes are difficult, especially, for inexperienced teachers. Iswati and Triastuti (2021) showed that conducting a pretest to group the ESP students depending on their skills is one technique to predict their variable competence. Yet, it costs time and money and requires a thorough planning. EBE teachers need to take into consideration the learners’ distinctive characteristics when preparing the course materials and tasks. They have to address as much students as they can through varying the content of lectures. Additionally, they can use pair work or group work as they are considered as one of the effective techniques that help students to learn from each other, interact and expand their skills and knowledge. Furthermore, creating a strong feeling of teamwork can result in increased motivation, a greater sense of shared responsibility, and can make the learning experience more pleasurable for all students (Dörnyei, 2001).

Motivation, is one of the main features that characterise language learners in a heterogenous class. All teachers-participants complained about their students’ low motivation as demonstrated in the following excerpts:

“They are demotivated and lazy. The majority do not do their assignments… Even those who attend the courses, just sit without participating or doing activities. I feel that they are reluctant except for some students” (P5)

“Students are demotivated especially here in UCM. There are some exceptions that we count with fingers.” (P2)

“Most of them do not have the motivation to learn English. They do not consider it as a primary module” (P1)

Classroom observation’ results also revealed that students were highly demotivated, and this was reflected in their absenteeism. Attendance during lectures was quite low, particularly among graduates. For example, over two months of classroom observation, the majority of Master 1 students in the two specialties1 were typically absent. Between 3% and 9% of students attended lectures, which is considered an extremely low percentage when compared to the total number of students (90 to 166 students). Additionally, significant absences were noted among undergraduate students. Even those who attended lectures demonstrated a lack of interest, as they talk and laugh throughout the session, ignoring the teachers’ instructions, playing games or chatting on social media, and completing work related to other modules. This implies that they attended EBE lectures only for the purpose of achieving the course’s average in their TD grade2

Several reasons stand behind the students’ lack of motivation. Firstly, their low English proficiency (i.e., the more competent the students are in English, the more motivated they are). Secondly and most importantly, the teaching methodology which plays an important role to build students’ motivation to learn the language. Some teachers claimed that they motivate their students as much as they can through varying materials and exercises. Yet, their claims were partly executed once in classroom. It was observed that students were demotivated and showed a feeling of boredom during English classes. This is probably due to the methodology of teachers who simply delivered direct lessons which are mostly content-based and focused mainly on vocabulary without including the four language skills (i.e., listening, speaking, reading and writing). The teacher explained, for example, some economic phenomena and translated the technical terminologies without using any kind of materials like visual or audio-visual aids, handouts, texts, videos, etc. Though one teacher-participant used the data show to deliver his lessons, but they are just written long texts, or some power point presentations downloaded from certain websites. Additionally, the interaction is totally absent between the teacher and the students. Surprisingly, it was observed that even activities and exercises are completely absent and ignored by some teachers during the courses.

The EBE teacher is responsible for pushing the students to learn through giving instructions and tasks to do in order to promote learners’ engagement. Rather than relying on direct lectures, teachers should increase their learners’ motivation and attract their attention, interests through using more innovative ways of teaching. Information and Communication Technologies (hereafter, ICTs) expertise are required. EBE teachers are encouraged to keep pace with the rapid advancements in ICTs in order to ensure that their students are well-prepared for the global marketplace. They can benefit from the use of ICTs by enhancing their traditional methods of instruction, making learning more engaging, and motivating students.

3.5. Challenges Concerning the Organisation and the Administration

In addition to various obstacles have been discussed, the findings cast a new light on some challenging factors related to organisation and administration. These latter are those issues concerned with the administration and the internal regulations of the institution.

In regard to classroom conditions, P3 and P5 noted that they teach large classes:

“The classes are at least crowded, if not overcrowded. One class often exceeds forty students and satisfying their needs will be more difficult” (P3)

“For classroom size, they are overcrowded classes. But when it comes to real context, I have many absences.” (P5)

Other teachers-participants claimed that they do not have a problem with the classroom size:

“Classroom size is fine” (P1)

“Though almost all my students attend my lectures, the class size is fine” (P2)

“Classroom size is good. I have the chance to have a balance between students so that I could control them. The department of Economic Sciences in UCM is very crowded to an extent that a classroom can exceed 40 students. But I usually have seven to eight groups and each one carries from 25 to 30 students” (P4)

As a matter of fact, classrooms are not considered sizeable because of the students’ absences as revealed by classroom observations. Undergraduate students are divided into groups which contain from 25 to 35 students each. However, all groups of Master students (graduates) are combined by the administration in one single class in each level and specialism. They carry a huge number of students (about approximately 90 to 166 students), while the ideal language class should not exceed twelve students (Brown, 2007). So, these classes are overcrowded which make teaching problematic and challenging. This fact broadly supports Hess’s (2001) view, who claimed that large classes are sometimes more exhausting and of course more demanding. The EBE teacher has to cope with various problems accompanied with large classes (i.e., students’ heterogeneity, maintaining classroom discipline, knowing all the students, satisfying their needs, correction of written tests and assignments, classroom management, etc.). This is primarily due to the lack of rooms that are very limited in UCM comparing with the total number of students especially as the department of economics share their rooms with other new created departments3

Moreover, the full-time EBE teachers are insufficient, forcing the UCM institution to hire part-time teachers who are frequently unprepared to deal with the new ESP teaching circumstances and earn a pittance for teaching and performing a variety of other duties:

“As you know, we usually enter as part-time teachers and we learn by ourselves. We do not know if we will be recruited to become full-time teachers. We know that we are just transient.” (P2)

Teachers also noted that the timetable is not suitable for both teachers and students. As opposed to other specialty’ modules, EBE module seems to be underestimated by some administrators in the Institute of Economic, Commercial and Management Sciences at UCM as it is considered secondary which has a coefficient of ‘1’. Thus, the timetable is usually undesirable for some teachers. They complained that the EBE courses are usually in the evening, and this affects students’ attendance and participation:

“For timing, I have some first-year classes at 4 p.m.” (P4)

“I have a problem in timetable. I usually teach Business English from 3 p.m. to 4.p.m. Therefore, I found my students exhausted and maybe hungry, etc. Time is very important. Of course, they always favour, for example, mathematics and economics because they require students to be fresh. So, they keep English at the end of the day. Students usually do not stay especially those who live far. They do not care about English. Here the problem is that there are not enough free rooms in the morning. So, they usually program English module in the evening.” (P3)

More consideration should be taken by the administration in scheduling the time of English module to be suitable and motivating for both teachers and students.

Furthermore, the amount of time allotted to EBE course is insufficient. Students have a session of one hour and a half per week. Yet, during Covid-19 pandemic the time has been decreased to become only one hour.

“We have a certain syllabus to cover and we do not have time.” (P3)

“Now during Corona, I feel it is not enough to deliver the whole content of the lesson. We usually have one hour and a half which is much better at least. But generally speaking, one session per week is not enough. It would be better if they make two sessions per week” (P4)

Data obtained from classroom observation also proved that EBE teachers had a big issue concerning class time which actually lasted for 45 minutes as most of the students were careless and usually came late. Teachers were unable to finish their lessons, and the one lesson usually required two sessions to be done. Because of the limited class time duration, teachers cannot conduct any type of needs analysis which is very important to be familiar with their learners. Besides, they cannot cover all units of the syllabus, and are unable to do the activities in order to assess and evaluate their students and provide the personal feedback. Consequently, students’ demands and expectations can hardly be satisfied and that in turn prevents the course’s objectives from being effectively reached.

It is also worth discussing that teachers have another issue related to the syllabus. This latter is either inadequate or completely absent:

“We should normally be guided with certain axes which have to be included in the canevas4… I think, for the novice teachers like myself I face a lot of difficulties on how to research and how to elaborate the final course” (P5)

“The administration just told me to teach them terminologies but which ones? There is no canevas. They just ask the teacher to teach terminologies about business and economics, or the teacher can suggest a syllabus to teach EBE.” (P4)

The syllabus should be more developed and detailed. Curriculum designers are responsible to design effective EBE syllabi with clear established objectives, content, evaluation criteria and teaching approaches. The provided course content is very broad and it needs to be clearly elaborated with themes, topics and sub-topics to be tackled in class. Due to the fact that EBE teachers, particularly novices, have never received prior ESP training, it will be difficult for them to start from scratch without a guiding syllabus.

Participant 3’s comment further suggested that EBE syllabus need to be convenient with students’ level:

“EBE syllabi are difficult for students who are not good enough in English language. There should be a gradation in their lessons. When we see the programs and lessons, the students have to master English to learn what is in their syllabus, and this not the case to our students”. (P3)

There is a discrepancy between the provided syllabus and students’ language competencies. As discussed above, the majority have a low language proficiency, low motivation and poor GE grammar. Hence, both syllabi writers and EBE teachers should take a real account to students’ needs analysis to design the appropriate and effective syllabi and courses accordingly.

4. Limitations, Implications and Further Research

This study has certain limitations. The main drawback of the current study is that it included a small sample and a single university center, i.e., it may not accurately reflect the overall state of EBE practice in a larger national or worldwide context. Thus, a more comprehensive setting for the study is definitely recommended in order to get more credible evidence. Furthermore, the current investigation was qualitative in nature; consequently, the findings’ analysis may be subjective. Thus, more on a similar problem utilizing a quantitative paradigm is needed. Regarding classroom observation, it was deemed undesirable for some teachers; consequently, they did not take long. Furthermore, classrooms were not observed on a consistent basis; rather, the observed sessions and classes were spaced between due to covid-19 quarantine that was beyond of the researchers’ reach.

Numerous conclusions are drawn from the current study, which should serve as a wake-up call to policymakers to prioritize ESP teachers’ education and professional development through the implementation of effective training programs. The identified challenges in this study will serve as a thorough needs analysis on which ESP teacher education programs may build their curricula that in turn can widely improve ESP/EBE teaching quality in Algeria. This study also suggested ways to overcome obstacles in teaching EBE at UCM.

Due to the various ESP/EBE teachers’ challenges resulting from primarily the absence of ESP teachers’ training in Algeria, further investigation should be conducted on the use of discourse analysis, as a self-learning method to hone teachers’ professional abilities, particularly in the area of specialized language knowledge, ESP course design and materials’ development.

Conclusion

This paper provides insight into the challenges that practitioners encountered when teaching EBE, and the possible solutions to the aforementioned issues. In light of the findings, it is clear that EBE teachers at UCM, have faced several challenges that need immediate resolution. The findings revealed that the primary challenges confronting EBE teachers include a lack of specialized language expertise, absence of ESP training, a lack of course materials, and a variety of other challenges (class heterogeneity, students’ low English competence, etc.). These connected issues are viewed as a significant impediment to improving the quality of EBE instruction. Notably, ESP teachers are the major source of language input to students, directly influencing the learning process. Hence, the study recommends a variety of solutions (integrated training programs, teachers’ collaboration, self-professional development, etc.) that EBE practitioners might use to overcome these challenges.